Bionic Jean’s

Comments

(group member since Jul 27, 2022)

Bionic Jean’s

Comments

(group member since Jul 27, 2022)

Bionic Jean’s

comments

from the Works of Thomas Hardy group.

Showing 101-120 of 2,004

Locations:

Locations:(Is this OK Bridget?)

A "mixen" is literally a place to lay dung!

As you say, Mixen Lane was a real place in Dorchester - actually in Fordingham ("Durnover") - described later as "a squalid area of slum dwellings where the only things that flourished were vice and crime". Most of the cottages had been pulled down by the time of the novel in 1884-5.

When Lucetta suggested that Elizabeth-Jane visit the museum:

It is an old house in a back street" she meant 3 Trinity St., a fine 18th century town house in Dorchester, functioning as the County Museum after 1851. Trinity St was then known as South Back Street:

(attributed to cmyk)

Thomas Hardy was one of the founders. Little did he know that so much of it would be devoted to him later! 🙂

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dorset_...

The episode today in ch 26, where Henchard and Farfrae meet by accident:

"in the chestnut-walk which ran along the south end of the town"

as you probably guessed, refers again to the Roman Wall. South Walk follows the course of the Roman Wall from The Junction at the end of South St to Icen Way.

ch 25 "Lucetta’s decision has a dramatic impact on multiple characters. Henchard, meanwhile, has been a slave to the past, with equally terrible consequences."

ch 25 "Lucetta’s decision has a dramatic impact on multiple characters. Henchard, meanwhile, has been a slave to the past, with equally terrible consequences."This is a great observation Bridget, perfectly contrasting the two. And Peter and other's concern for Elizabeth-Jane, who functions as an observer in these scenes (as Claudia rightly pointed out) matches mine. Poor Elizabeth-Jane - and how skilful of Thomas Hardy to convey so effectively the emotions and attitude of someone who is an observer, and not centre stage at all!

(Sorry for the backtrack! I was in Thomas Hardy's "Port Bredy" (Bridport) yesterday, 14 miles from "Casterbridge" at a folk festival in Bucky Doo Square (in the town centre). Some of the traditional sets really did make me think of Thomas Hardy leafing through his family's pile of sheet music and humming to himself 🙂)

On to today ...

So we see that Thomas Hardy is keen for us to think of these images of oil paintings, when we observe Lucetta's posed attitude, but I feel it's more than this. Lucetta herself has had a European education, and will be well aware of these famous paintings and the erotic tradition. I think what she may have in mind are the dual paintings which sprang to mind for me when I read the scene. Here they are:

So we see that Thomas Hardy is keen for us to think of these images of oil paintings, when we observe Lucetta's posed attitude, but I feel it's more than this. Lucetta herself has had a European education, and will be well aware of these famous paintings and the erotic tradition. I think what she may have in mind are the dual paintings which sprang to mind for me when I read the scene. Here they are:

The Clothed Maya (Spanish: La maja vestida)

The Naked Maja (Spanish: La maja desnuda)

Both are by Francisco Goya, another Spanish painter, and painted between 1797 and 1800. Lucetta will have known these works well, and I suspect is deliberately suggesting the second, (perhaps as a subliminal idea, if her viewer e.g. Henchard was not as educated in the Arts).

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/La_maja...

And now we also have the red dress 😲! What a choice - it suggests a scarlet woman! (I seem to remember this filtered into America society too eg. Gone With the Wind). Even in the early 20th century, English people would looks askance at a respectable female wearing a red dress.

Plus the act of ordering Paris - or Paris-type - fashions is the habit of a fashion-conscious, stylish woman. Most English females of this era bought fabric, and either made it up themselves if they were not well off, (Elizabeth-Jane would have done this) or had a favourite dressmaker to make it up for them, if they were genteel. Lucetta though is even bolder in making good use of her money to attract admirers! Her frank conversation with Elizabeth-Jane shows her thoughts, in this case, that she "would become" the person suggested by the gown.

Gosh, so many signals of what type of woman Lucetta is!

So many great comments here, and thanks for taking the baton and running with it so splendidly Bridget! I too thought of Tess with the "blighted star", and also the comparison with the monster of a new farming machine Erich mentions, which is also in both novels.

So many great comments here, and thanks for taking the baton and running with it so splendidly Bridget! I too thought of Tess with the "blighted star", and also the comparison with the monster of a new farming machine Erich mentions, which is also in both novels.Erich - thanks for directing us to the "Sleeping Venus", which I always thought was by Giorgione, and merely completed by Titian, 🤔but now see the attribution has changed. Lucetta's artful position also reminded me of "The Rokeby Venus" in our National Gallery, also known as "The Toilet of Venus" a painting by the Spanish painter Diego Velázquez, and created between 1647 and 1651:

It depicts Venus, the Roman goddess of love, reclining on a bed with her back to the viewer. The painting is famous for its erotic charge, its depiction of a reclining nude, and its controversial history. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rokeby_... To me, this gaze at the reflection of herself is key with Lucetta, who is almost narcissistically keen to present herself as youthful and vivacious.

In ch 24 she even quizzes Elizabeth Jane about her looks. In Robert Barnes' illustration though, (thanks Bridget) his realistic comparison of the two perfectly captures Lucatta's older face and expression. Plus Thomas Hardy reminds us again in ch 24 that Lucetta is older, more experienced and adds that she knows how to talk to men to get what she wants. She is flirtatious for sure!

The historical information about Jersey is fascinating, thanks Claudia!

The historical information about Jersey is fascinating, thanks Claudia! I have never been there, but like you, do know Guernsey, having been there twice. Jersey is the largest of the Channel Islands (other small ones include Alderney, Sark and Herm - I have been to these too) but they are not one political unit. Simplifying this, there are two independent Bailiwicks: Guernsey and Jersey, with Jersey as the most French, being closest to France and having the history Claudia explained so well.

Bath was stylish both then and now, (and loved by Jane Austen) although plenty of tourists go there.

Evidently Jersey society must have been different from how it is now. The reason Jersey is the only Channel Island I have not been to is because it is full of millionaires, with aspirational people, a high standard of living and prices to match! There are lots of tax exiles from Britain living in Jersey. Michael Henchard would not fit in!

I think this is quite a recent phenomenon though, as even as recently as the Second World War it was a simple island as Claudia describes. Interestingly Guernsey and Jersey were both occupied by the Nazis then: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/German_...

because of their advantageous positions for invasion.

So we wonder about the history of Miss La Sueur - and her change of suffix from Lucette to Lucetta - great point that it feels more cosmopolitan Claudia! And where her inherited wealth originally came from.

Peter - I loved your analysis of the illustration, and highlighted the same sentence that Claudia did!

Kathleen - Thank you so much! Yes, perhaps Thomas Hardy gave us enough pieces of the jigsaw for us to work out who the mystery woman was, but it's still a great feeling to be proved right, I think 🙂

What a great cliffhanger - of the many we have had so far - and at this point I hand over to Bridget for the second half of the novel starting tomorrow.

What a great cliffhanger - of the many we have had so far - and at this point I hand over to Bridget for the second half of the novel starting tomorrow. Thanks all for making this such an enjoyable read so far, and adding so much depth with your observations. I'm so glad you appreciate my "local knowledge" and can hardly wait for the second half!

Lucetta’s focus on Henchard is explained as practical rather than emotional. She is more interested in preventing gossip about her past than in marrying for love. The effects malicious gossip could have at this time period, especially about an unwed female could be pernicious. Lucetta, with her newly acquired wealth, desires to be successful in the eyes of society.

Lucetta’s focus on Henchard is explained as practical rather than emotional. She is more interested in preventing gossip about her past than in marrying for love. The effects malicious gossip could have at this time period, especially about an unwed female could be pernicious. Lucetta, with her newly acquired wealth, desires to be successful in the eyes of society. Henchard is inspired by Lucetta’s letters, but angered by her acting as if she is now a great lady. Henchard’s reaction to such treatment is characteristically one of pride: he will not humble himself, but will wait for her to come to him.

Elizabeth-Jane feels guilty because she believes Henchard is staying away because of her. Lucetta too feels she has prevented the very thing she wanted through her own scheming, so she schemes some more (!) and plans to get Elizabeth-Jane temporarily out of the way. She does not realise that Henchard is in fact staying away as a response to Lucetta’s airs, which he perceives as vanity, and is waiting for her to reach out to him. Lucetta blames Elizabeth-Jane for a situation outside of Elizabeth-Jane’s control.

Once Elizabeth-Jane has gone, Lucetta reaches out to Henchard. She seems to be direct and forward with Henchard when she is attempting to secure her position. But her sudden shyness means that she is left alone with a different visitor who arrives because she has sent Elizabeth-Jane away.

The end to this chapter seems almost like a tableau to me, as we take a deep breath - again!

The end to this chapter seems almost like a tableau to me, as we take a deep breath - again!On hearing that Elizabeth-Jane is moving to High-Place Hall, Henchard realises with a jolt that her move must have been the intentional plan of the woman living there. Lucetta’s note to Henchard expresses her hope of reconciliation and Henchard connects this to High-Place Hall because a woman named Templeman, Lucetta’s relative, is moving in there.

Then he and we both learn of Lucetta’s change of name, which she reveals to Henchard in a second note. This reflects two things:

1. It shows her desire to hide her past, which is linked to her real last name. Several have commented how intriguing this plot-line is, and now I’m wondering about her past!

2. It shows the dramatic change of situation Lucetta has experienced because of the money she has received from her relative named Templeman.

Lucetta’s perspective on Elizabeth-Jane’s move as a “practical joke” shows us that Henchard, and not her sudden “friendship” with Elizabeth-Jane, is her priority. As Claudia pointed out with her quotation, Elizabeth-Jane is extremely interested in her, and we know Elizabeth-Jane's honest motives, but have many indications in the text (nice catch Peter that High-Place Hall may reflect the personality of its occupant!) so that all may not be as it seems. For instance Lucetta must be several years older than she behaves and appears.

She seems nice enough, but rather devious. Should we trust Lucette/Lucetta Le Sueur/Templeman? On the other hand, so many people have concealed secrets in this novel; perhaps this one is relatively minor.

Although Lucetta’s partial confession of her past and her previous identity might have been a mistake with another listener, it is safe with Elizabeth-Jane. In many ways, Elizabeth-Jane, although younger, is more mature than Lucetta in her discretion, her emotional support, and her ability to focus on others rather than drawing attention to herself.

Lucetta prepares carefully for Henchard’s visit, which shows she is interested in catching his attention. The market day scene provides a venue for Lucetta and Elizabeth-Jane to observe life in Casterbridge. Elizabeth-Jane does not admit her affection for Farfrae to Lucetta because she is unwilling to admit it even to herself.

And a little more …

And a little more …Lucetta does not want to be identified as the young Jersey woman:

“She shirked it with the suddenness of the weak Apostle at the accusation, “Thy speech bewrayeth thee!””

After Christ’s arrest Peter denied being one of his followers, but he was identified by his Galilean accent (Matthew 26. 73)

“Tuesday was the great Candlemas fair.”

The feast of thanksgiving for the Purification of the Virgin, now February 2nd. The hiring fair in Dorchester (“Casterbridge”) which we’ve come across before e.g. in Far From the Madding Crowd, at which agricultural workers were taken on for the coming year, took place on Old Candlemas day, February 14th.

Chapter 22

Chapter 22Henchard’s stunned reaction to Elizabeth-Jane’s new address is explained by the events of the previous evening. Henchard had then received a letter from “Lucetta”. This was the young woman whom he had known in Jersey by the name “Miss Lucette Le Sueur”. In this letter, Lucetta wrote that she had heard of Susan’s death and felt in these circumstances that she must reach out to Henchard in the hope that he would keep his previous promise to her. Henchard had already learned that a lady of the last name Templeman, which he knew was the name of Lucetta’s remaining relative, had purchased High-Place Hall.

When Henchard visited High-Place Hall the previous evening, he inquired after Miss La Sueur (the last name by which he had known Lucetta) and heard that only Miss Templeman had arrived. Henchard wondered if Lucetta had come into some money through her relations with the Templeman relative she had spoken of.

The next day, soon after Elizabeth-Jane’s departure, Henchard receives another note from Lucetta explaining that she is in fact, the “Miss Templeman” in residence, having taking her rich deceased relative’s name along with her inheritance. She writes lightly, referring to the “practical joke” of getting Elizabeth-Jane to live with her, and says she has moved to Casterbridge so that Henchard might easily visit her.

Henchard’s excitement and hopes for Lucetta are greatly increased by her letters and he sets out that very night to visit High-Place Hall. However, upon calling, he is told that Lucetta is engaged that evening, but would be happy to see him the next day. Henchard exclaims at Lucetta giving herself such airs and resolves to likewise make her wait to see him.

Earlier in the evening when Elizabeth-Jane arrived at High-Place Hall, she had joined Lucetta in the drawing room where the other woman endeavoured to entertain her with some card tricks. Instead, the two women have a conversation in which Lucetta shares the story of her newly received fortune. She also tells Elizabeth-Jane about her true home in Jersey, although she had arrived in Casterbridge from Bath. Lucetta could not have confessed these details to a safer person than Elizabeth-Jane, who tells no one else.

The next day, Lucetta dresses for Henchard’s visit and waits for him all day. She does not tell Elizabeth-Jane who they are waiting for. It is market day, and the two women watch the action below in the square. Elizabeth-Jane sees Farfrae and then her father, as the pair encounter each other, and observes that Henchard clearly refuses to speak to the younger man. Lucetta asks Elizabeth-Jane if she is particularly interested in any of the men she sees below, but she says no, despite her blush.

Lucetta is disappointed that Henchard did not visit, despite having spent the day nearby in the square. She supposes he was busy, and that he will come on Sunday or Monday, but he does not. Lucetta no longer loves Henchard as she once did, but she wishes to secure her position. On Tuesday, the Candlemas Fair calls the merchants back into the market square. Lucetta wonders aloud to Elizabeth-Jane if her father will visit her today because he will be coming for the fair. Elizabeth-Jane says he will not come because of his grudge against her.

Lucetta starts to cry as she realises that she has prevented Henchard from visiting by inviting Elizabeth-Jane to live with her. Lucetta says that she likes Elizabeth-Jane’s company very much, and the younger woman feels the same way. Lucetta devises an errand to send Elizabeth-Jane away from the house that morning, so that Henchard may visit. Elizabeth-Jane senses that Lucetta wants to get rid of her that morning, but does not understand why.

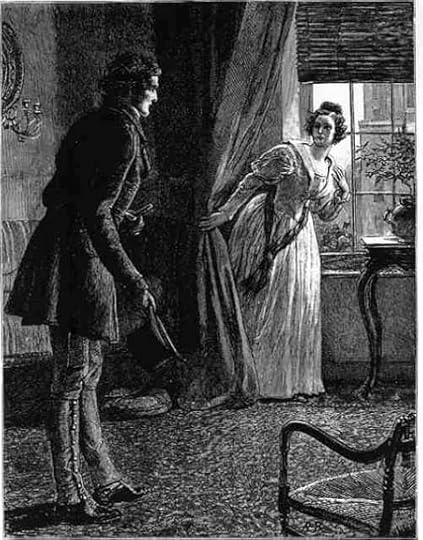

As soon as Elizabeth-Jane has departed, Lucetta writes to Henchard explaining that she has sent Elizabeth-Jane away that morning so that he may visit. Finally hearing a man being shown into the house, Lucetta hides behind the curtains in the drawing room, suddenly timid. But when she throws back the curtain, she discovers that the man who has been shown in is not Henchard.

“The man before her was not Henchard” by Robert Barnes - 6th March 1886

I'm delighted by everyone's astonishingly perceptive comments on the subtext of these latest chapters, thank you! Thomas Hardy is such a master of giving us information bit by bit, so let's see what he has in store for us today.

I'm delighted by everyone's astonishingly perceptive comments on the subtext of these latest chapters, thank you! Thomas Hardy is such a master of giving us information bit by bit, so let's see what he has in store for us today.

Pamela wrote: "wouldn't both Elizabeth-Jane and Henchard still be mourning ..."

Pamela wrote: "wouldn't both Elizabeth-Jane and Henchard still be mourning ..."Yes, and since I assume they would be classed as immediate family, it would be full mourning. The men's attire was just as strict! And I agree, his entering a single woman's house alone would be unseemly.

We now have a free day, and will read chapter 22 on Tuesday 22nd July

We now have a free day, and will read chapter 22 on Tuesday 22nd July I can't wait to read everyone's reactions to this new development!

High Place Hall occupies Elizabeth-Jane’s mind as her future home and as the residence of her new friend, Miss Templeman. Elizabeth-Jane’s confidence - almost brazenness - at entering the house, shows her already strong feeling of connection to this woman whom she barely knows. Finding a companion marks a distinct change in her life. Yet the hidden door that she encounters could represent a darker side to High Place Hall. Perhaps there are signals here that there are yet more secrets that she doesn’t understand.

High Place Hall occupies Elizabeth-Jane’s mind as her future home and as the residence of her new friend, Miss Templeman. Elizabeth-Jane’s confidence - almost brazenness - at entering the house, shows her already strong feeling of connection to this woman whom she barely knows. Finding a companion marks a distinct change in her life. Yet the hidden door that she encounters could represent a darker side to High Place Hall. Perhaps there are signals here that there are yet more secrets that she doesn’t understand.Elizabeth-Jane and the woman both arrive at the graveyard, despite the poor weather. Evidently both are eager to start their new living arrangements, but is there anything unusual in the mystery woman asking Elizabeth-Jane’s father knows where she is moving to? Straightforward Elizabeth-Jane however, is not suspicious. However, since Henchard deliberately enters the house through a secret doorway, perhaps we should be! His business there and his connection to the woman are evidently both secrets. Elizabeth-Jane’s request to move out pleases Henchard. His offer to support her financially is a generous one, because he believes he is not responsible for this young woman whom he now knows is not his daughter.

But then Henchard’s last minute change of heart is motivated by his selfishness. He sees that Elizabeth-Jane has tried to improve herself through study; evidence to him of the influence Henchard has over her. It is only when he realises that he will lose her that Henchard sees some of her value and importance, even as only his stepdaughter.

Elizabeth-Jane sticks with her plan to leave, for once doing something for her own happiness rather than another’s.

And Yet More …

And Yet More …Victorian Mourning Traditions

Deep Mourning

This was the most restrictive phase, requiring plain, dull black fabrics like crape (a crinkled fabric) or wool, with minimal or no ornamentation. Women wore veils and bonnets made of crape, and jewelry was limited to plain jet or black beads. Since Miss Templeman had a veil, she might have been dressed like this.

Ordinary or Second Mourning

This allowed for the introduction of black silk and more elaborate trimmings like jet beading. Jewelry was still understated but could include pieces like black or jet brooches or bracelets. Since Elizabeth-Jane noticed she was stylish, she could well have been dressed like this.

Half-Mourning

This final stage allowed for the use of grey, purple, and lavender, or a combination of black and white. Fabrics could be fancier like silk and velvet. The mysterious Miss Templeman could even have been dressed in this way. I quite like to think of a mysterious veiled but stylish lady dressed in lavender, which would really have impressed Elizabeth-Jane - but then a beaded black gown of a quality material would also have had this effect.

The length of time a person was expected to wear mourning clothes varied depending on their relationship to the deceased. Widows, for example, wore deep mourning for a year and a day, followed by a second year of mourning with half-mourning colours.

The intriguing question to me therefore, is:

Who is “Miss Templeman” in mourning for, and what was her relationship to them?

And a little more …

And a little more …Locations

Miss Templeman has been staying in “Budmouth”, which is the fictional name Thomas Hardy uses for the seaside resort of Weymouth. You might remember that this town played an important part in Tess of the D’Urbervilles.

She then takes up residence in High Place Hall, which is in reality Colliton House, Dorchester

Colliton House, Glyde Path Road, Dorchester - (Jo and Steve Turner - creative commons reuse)

It has a datestone of 1729 probably reflecting the later alterations. The information plaque reads 'Formerly the town house of the Churchill family. Mainly 17th century with major 18th century alterations.' The site is believed to be the location of the medieval hospital of St John the Baptist, fragments of which may still remain in the building and its foundations.

Since 1933 it has been part of Dorset’s County Hall site. Thomas Hardy places it overlooking the market place, which is some distance South East of its true position. It seems a strange idea for the evidently wealthy (by her dress) Miss Templeman to deliberately rent something overlooking a busy market. Is this significant do you think? Can we think of a possible reason for this?

“the keystone of the arch was a mask. Originally the mask had exhibited a comic leer, as could still be discerned; but generations of Casterbridge boys had thrown stones at the mask, aiming at its open mouth; and the blows thereon had chipped off the lips and jaws as if they had been eaten away by disease.”

This does not seem to bode very well! In fact the archway which formerly led to a yard and brewery at the rear of Colliton House is preserved in the County Museum above the library door.

The Dorset County Museum now houses both the Jacobean wall and the archway from the house on Colliton Walk (called "Chalk Walk" in Ch. 9 of the novel), mask and all. Could the hideousness of the mask, defaced by time, be a symbol for something?

Chapter 21

Chapter 21Elizabeth-Jane’s imagination fills with the prospect of the fine lady, her new house in Casterbridge, and the possibility of her living there. One early evening, Elizabeth-Jane decides to walk up to the house, High-Place Hall, which she had passed many times, but which had never before taken on particular meaning. The new lady now occupies the house, and Elizabeth-Jane sees lights in the upper rooms. The architecture of the house is fine, but it overlooks the marketplace, which might be seen to be undesirable.

The removals men are going in and out of the house, and Elizabeth-Jane enters as well through an open door. Startled by her own brazenness, Elizabeth-Jane quickly exits through another open door and finds herself in a little-used alleyway. Turning to look back at the door by which she had exited, Elizabeth-Jane sees that is was an old doorway, older than the house itself, and decorated with a masked face, decayed and worn away by age. The secret doorway with its grim face constitutes the first unpleasant aspect of Elizabeth-Jane’s visit.

Hearing approaching footsteps, Elizabeth-Jane hides from another passerby in the alleyway before heading home. Had she lingered, she would have seen the other person was Henchard who enters by the secret doorway. He returns home not long after Elizabeth-Jane and she decides to ask him if he would allow her to move out of the house. He has no objection and offers to make her an allowance, so she can live independently. He seems relieved to part from Elizabeth-Jane and any responsibility toward her.

Elizabeth-Jane returns to the graveyard to meet the lady and finds her there despite the poor weather. The woman invites her to move in immediately. The two women overhear voices from beyond the churchyard wall, one of which Elizabeth-Jane identifies as her father’s. The woman suddenly asks whether or not Elizabeth-Jane told her father where she was moving. After Elizabeth-Jane negative reply, the woman realises she never gave her name and introduces herself as Miss Templeman.

Miss Templeman arranges for Elizabeth-Jane to arrive at her house and move in at six that evening. Henchard is surprised when he arrives home to see Elizabeth-Jane departing so promptly. He asks her if departing with so little warning is any way to treat him for his trouble taking care of her. Henchard goes to her room to look over the moving of her things, and sees all her efforts to study and improve herself. In a sudden change of temperament, he implores Elizabeth-Jane to stay with him saying that something specific has grieved him, which he cannot yet confess to her.

Henchard’s change of heart comes too late and Elizabeth-Jane is determined to leave. She promises she will return though, if her father needs her, and she leaves, saying she is heading to High-Place Hall.

I love all these ideas, and am intrigued by the idea of the mysterious lady as a literary doppelganger, much loved by readers of Victorian fiction, as Claudia and Peter have said.

I love all these ideas, and am intrigued by the idea of the mysterious lady as a literary doppelganger, much loved by readers of Victorian fiction, as Claudia and Peter have said.Just to add ... we don't actually know that she is all in black (although it's likely). We are told she is in mourning and the Victorians had strict codes for this, which I'll add after today's chapter.