Kalliope’s

Comments

(group member since Aug 28, 2018)

Kalliope’s

Comments

(group member since Aug 28, 2018)

Kalliope’s

comments

from the Ovid's Metamorphoses and Further Metamorphoses group.

Showing 481-500 of 610

On Envy, the illustration I find is from Flemish engraver.

On Envy, the illustration I find is from Flemish engraver. Godfried Maes. Envy. Between 1664 - 1700.

I found the passage on Envy very striking. The Notes in my text say that IN-VIDIA, in Latin, 'refers to a flawed act of vision' - and draws attention to the many terms that refer to vision, and looking, and eyes, and images in the text.

I found the passage on Envy very striking. The Notes in my text say that IN-VIDIA, in Latin, 'refers to a flawed act of vision' - and draws attention to the many terms that refer to vision, and looking, and eyes, and images in the text.

Roman Clodia wrote: "We can also find parallels with Io in that Callisto is silenced ('her powers of speech were wrested away,' 2.483), but her human consciousness still remains, at odds with her body: 'but though her body was now a bear's, her emotions were human,' 2.485.

Roman Clodia wrote: "We can also find parallels with Io in that Callisto is silenced ('her powers of speech were wrested away,' 2.483), but her human consciousness still remains, at odds with her body: 'but though her body was now a bear's, her emotions were human,' 2.485...."

The instances in which speech - or loss thereof - is another running theme... I believe RC has commented on this already... We fist had Io, but now also the greatest 'speaker' so far, Ocyrhoe, the one who speaks that which has not yet happened, is also silenced. She is not even allowed a human upper body since that would still allow her to speak.

Roman Clodia wrote: "Thanks Kalli - this looks similar to (but isn't) the engraving that was included in the George Sandys 1632 illustrated edition of the Met. where each illustration comprised various episodes from th..."

Roman Clodia wrote: "Thanks Kalli - this looks similar to (but isn't) the engraving that was included in the George Sandys 1632 illustrated edition of the Met. where each illustration comprised various episodes from th..."Thank you, RC.. I was unfamiliar with those by George Sandys.

For the Battus and Mercury episode, we have again a print interpretation.

For the Battus and Mercury episode, we have again a print interpretation.Battus is in the process of becoming a stone. 'That stone will talk before I do'

I'm sorry but I have no details on the image. Note that the subtitle is in French.

It shows Apollo, the owner of the cattle, distracted while playing his pipe, and not noticing how Mercury steals away his sheep. Then in the foreground is Mercury again, without his accoutrements, bribing Battus and punishing him into his stony metamorphosis. The horse/mare on the left - could that be a reference to Ocyrhoe?

Roman Clodia wrote: "Ovid himself, of course, is also a mediator, rather than originator, of many of these myths. It's easy to slip into thinking of his versions as sources in their own right.

Roman Clodia wrote: "Ovid himself, of course, is also a mediator, rather than originator, of many of these myths. It's easy to slip into thinking of his versions as sources in their own right. ..."

I keep thinking of this, RC, given that his readers would have been a great deal more familiar with other accounts than what we are today.

I also ask myself why was Ovid the preferred textual source for the painters from the Renaissance onwards.

May be it is Ovid's playful note, as well as his concerns with literary creation and expression, which allowed the stories to be exploited for their sensual and entertaining aspects - since the ethical /moral messages were expressed instead mostly through religious themes.

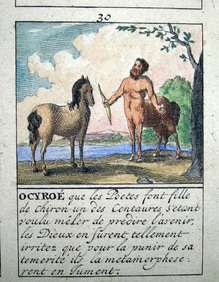

Of the Ocyrhoe story I have found only engravings.

Of the Ocyrhoe story I have found only engravings.Antonio Tempesta. 1606.

But she is shown as half human, like her father the Centaur Chiron, although she wonders in the text why she has been metamorphosed into a complete mare instead of retaining half her human figure.

This other one seems to be closer to the text... Rather nice, I think.

Roger wrote: "All true, but you still haven't explained those two at the top left of my detail "

Roger wrote: "All true, but you still haven't explained those two at the top left of my detail "I'm sorry, Roger, but I am afraid I don't hold the key to 'explaining' Poelenburgh's painting.

As I said, I see all the other nymphs in the complete picture as forming a 'domestic' arrangement - we are peeking into their private coterie: bathing, talking to each other and then the 'drama' of the pregnancy discovery. And I put the inverted commas to the 'domestic' because it is a quality so often associated with Dutch (bourgeois) painting -- an idea that the Seminar I have been attending has been trying to dilute - but which still pervades the approach to story-painting, however incidental in a landscape, in C17 Netherlands.

But may be you see something else.

Poelenburgh painted many more landscapes with Nymphs. They were very successful amongst his patrons which included King Charles I.

And there is at least one more with Callisto and Diana - this one in a private collection in NY.

Roger wrote: "I am providing a close-up:.."

Roger wrote: "I am providing a close-up:.."Thank you for the close-up, Roger. It is needed... The landscape was Poelenburgh's interest, but for us it is the Callisto story.

It was unknown to me until this afternoon.

Indeed, Diana is the one with the yellow robe... but whose face we cannot see, as I said above... the expressions of the nymphs who look at her act almost as mirrors for us to 'see' the horror that the goddess is discovering...

The whole scene also has a certain 'domestic' (and Dutch) aspect - showing other nymphs engaged in other activities, still oblivious of Callisto's drama.

Peter wrote: "One more thing that the physicist inside me appreciates: the enlivenment of the celestial constellations. There are on one side the wild animals that Phaeton must avoid, the hors of horns of Taurus..."

Peter wrote: "One more thing that the physicist inside me appreciates: the enlivenment of the celestial constellations. There are on one side the wild animals that Phaeton must avoid, the hors of horns of Taurus..."Peter, when I read this passage I thought of the comment you would be writing on this - giving us a further insight.

I had not thought of the etymology of 'settentrione' - in Spanish 'septentrional'.

Thank you.

Roger wrote: "Callisto Paintings: heroic, and not so much

Roger wrote: "Callisto Paintings: heroic, and not so much."

Today I was in a Seminar on the Dutch 'Italianate landscape painters of the C17 and the following was shown...

Cornelis van Poelenburgh. First Half C17. Hermitage.

Apart from the lovely landscape, I find interesting the whole 'coterie' of nymphs and the very subtle depiction of the tension when Diana is discovering Callisto's state.... Two of the nymphs are looking with apprehension at the goddess and Callisto is looking away.

We do not see Diana's face..

Roger wrote: "But Jupiter appears in so many forms: bull, swan, shower of gold, misty cloud. Testosterone for the bull, yes, but for the cloud?..."

Roger wrote: "But Jupiter appears in so many forms: bull, swan, shower of gold, misty cloud. Testosterone for the bull, yes, but for the cloud?..."That may be is the only attractive aspect of Jupiter, his malleability - always in the service of lechery and deceit, though... He is a comical figure...

Of all the 'creations' or 're-creations' of the universe, before it was first put in order or after a disaster, this is the first time that Jupiter has any doing in the restoration.

He not only stops the Phaeton disaster but also checks that everything is back in order -- paying closer attention to 'his' area, Arcadia, and as soon as it is possible, identifying his next pray. Incorrigible.

Anyway, all the previous times, it was not him the 'doer'.

Jim wrote: "The snorting, aggressive, testosterone-driven image is impossible to ignore. ..."

Jim wrote: "The snorting, aggressive, testosterone-driven image is impossible to ignore. ..."Yes. Impossible to ignore.

One of my editions (I am juggling three) has a note on the last line of the Callisto episode. She is identified as a daughter of Lycaeon. This is an inconsistency for in theory all human kind were destroyed with the exception of Deucalion and Pyrrha.

One of my editions (I am juggling three) has a note on the last line of the Callisto episode. She is identified as a daughter of Lycaeon. This is an inconsistency for in theory all human kind were destroyed with the exception of Deucalion and Pyrrha.

Roger wrote: "

Roger wrote: "I might as well post the great Titian painting of Diana discovering Callisto's pregnancy, one of the seven "poesies," or scenes from Ovid, painted for P..."

I have just reread the Callisto episode and looked again at your images, Roger. All very powerful and effective in their different way. I have paid more attention to the earlier scene, that of the seduction for, as you say, it provided a 'different' erotic scene. It makes me wonder how they were perceived by either gender.... Interesting that at least three Bouchers have survived. My favourite is the Kansas one.

I also like the Rubens (I always like the Rubens)...

Although a different 'theme', the pictorial rendition of this seduction scene made me think of the later and very daring painting.

Courbet. Le Sommeil. 1866. Petit Palais, Paris.

Roger wrote: "the hands-down winner for me is the Jordaens, largely because of the strength of his drawing of the foreshortened figure, and the trompe-l'oeuil effect of having him br..."

Roger wrote: "the hands-down winner for me is the Jordaens, largely because of the strength of his drawing of the foreshortened figure, and the trompe-l'oeuil effect of having him br..."Yes, and remember that this ceiling medallion Jordaens painted for his own mansion.

I liked the 'overperfumed' expression for Moreau... I agree he is somewhat of an 'acquired taste' - but many of the younger French painters found him very inspiring.... I don't like the lion - the rest I do.. so fantastical...

Roman Clodia wrote: "Women authors in the C16th-17th centuries seem to be more attracted to Ovid's Heroides which enable female authorship.

Roman Clodia wrote: "Women authors in the C16th-17th centuries seem to be more attracted to Ovid's Heroides which enable female authorship. ..."

I guess I will have to read the Heroids after the Met..

:)

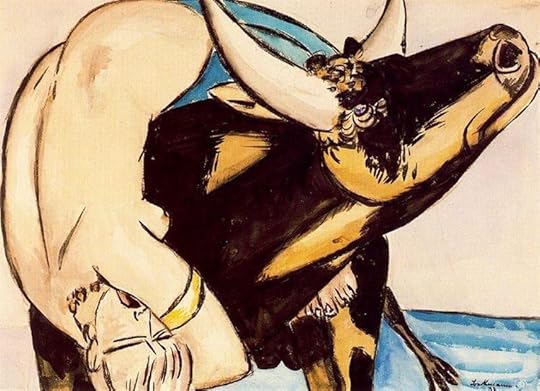

Roger wrote: "I believe Kalliope will be posting some pictures of Europa—and there are so many to choose from! But she probably won't choose this, which I found on the web. No information whatever, except the na..."

Roger wrote: "I believe Kalliope will be posting some pictures of Europa—and there are so many to choose from! But she probably won't choose this, which I found on the web. No information whatever, except the na..."Thank you, Roger.... No I did not know this image... intriguing indeed, as you say... Europa seems somewhat blasée about it all.

The image is also striking because the bull, the sea, and even Europa seem petrified. Out of stone.

I will be posting on Europa later on, as I have read the text more closely, and there are certainly many to chose from.. I wonder why was it such a popular subject.

But today I was the whole day in a Symposium on the German painter Max Beckmann, at the Thyssen museum, and they showed this one, which I had never seen before.

Max Beckmann. 1933. Private Collection.

Check the year... the political charge is substantial....

Fionnuala wrote: "

Fionnuala wrote: "How amazing it must be to stand beneath such a tumbl..."

Thank you... I hope the posting of images brings out the text in a different way...

And yes, the Phaeton is a perfect subject for a ceiling depiction.

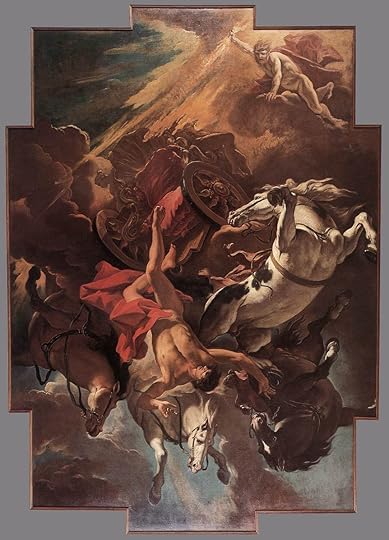

On paintings on the Phaeton episode. I posted above the Rubens because I was familiar with it already, but I have now searched a bit and found some other very interesting images.

On paintings on the Phaeton episode. I posted above the Rubens because I was familiar with it already, but I have now searched a bit and found some other very interesting images.Poussin shows us the section before the fall, when Phaeton is kneeling in front of his father praying to let him use the chariot. He is rather strong, not the youth we/I imagine from the story who cannot hold the reins. Helios is sitting on a 'sunny arch'. On the left I can only see one white horse and the chariot can be glimpsed.

Nicolas Poussin. 1635. Berlin Gemäldegalerie.

Unsurprisingly, Anthony Van Dyck also depicted Phaeton's fall spectacularly. As a pupil of Rubens, this kind of subject would appeal to him. It is a much later painting. As said above Rubens while still in Italy and when young and still in Italy. I don't know whether VD had seen the one by his master.

Van Dyck's composition is simpler in the sense that he has singled out the four horses falling spectacularly, the loose chariot and the helpless Phaeton.

Van Dyck. 1635. Prado Museum.

Then also in Rubens's circle we have Jordaens treating the scene for a ceiling medallion - which has the extraordinary effect of us feeling how he is falling on top of us and that we will also be drawn into the disaster that he has caused. It belongs to a series on the Zodiac signs. He originally painted them for his own mansion in Antwerp, but are currently in Paris since 1802.

Jacob Jordaens. Falling Phaeton. 1641. Palais du Luxembourg, Paris.

And one more, that also looks to be on a ceiling:

Sebastiano Ricci. 1703. Museo Civico de Belluno.

And now we jump to the C19, with another likely painter to treat such a subject, Moreau.

Gustave Moreau. 1878. Louvre.

For anyone visiting Paris, I recommend to visit Moreau's house, now a Museum.