Early American Government and Society > Likes and Comments

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

message 1:

by

Alan

(new)

Aug 10, 2021 01:45PM

This topic is being created at Feliks’s request. For Roger Williams, seventeenth-century New England theocracy, and matters pertaining to Williams’s new settlement of Providence and later colony of Rhode Island, see the topic Roger Williams (ca. 1603-1683) and Seventeenth-Century Rhode Island Government.

This topic is being created at Feliks’s request. For Roger Williams, seventeenth-century New England theocracy, and matters pertaining to Williams’s new settlement of Providence and later colony of Rhode Island, see the topic Roger Williams (ca. 1603-1683) and Seventeenth-Century Rhode Island Government.

reply

|

flag

My thanks for this opportunity.

My thanks for this opportunity. I was inspired by comments on historian David Hackett Fischer in the https://www.goodreads.com/topic/show/... thread, to air some further thoughts on early American settlements, the original thirteen colonies, etc --and to ask other members for their opinions.

For example, mention is made in passing, (in that law discussion) of Fischer's 900+ page opus, "Albion's Seed: Four British Folkways in America", Vol. I.

There are other fine historians and other fine books about this intriguing timeperiod (which likely, too few of us have read). However, Hackett's theory is particularly engaging and also lends itself readily to inspection.

Not to dwell too specifically about the "Albion's Seed" theory --but when I became acquainted with his premise it did make me wonder: just how much familiarity do I have, with early Americans?

In the aim of improving my knowledge, the following are some informal notes I've cribbed from a review of Hackett's assertions and though trivial (I think) they are stimulating in themselves. They help bring the early English settlers into focus.

Who exactly were the Quakers and the Puritans? This thread is a place to contribute impressions (and anything else we may come across in our various readings).

For example, those Puritans. Fun facts about Puritans!

1. Sir Harry Vane, who was “briefly governor of Massachusetts at the age of 24”, “was so rigorous in his Puritanism that he believed only the thrice-born to be truly saved”.

2. The great seal of the Massachusetts Bay Co. “featured an Indian, with arms beckoning, and five English words flowing from his mouth: ‘Come over and help us'”

3. Northern New Jersey was settled by Puritans who named their town after the “New Ark Of The Covenant” – modern Newark.

4. Massachusetts clergy were very powerful; Fischer records the story of a traveller asking a man “Are you the parson who serves here?” only to be corrected, “I am, sir, the parson who rules here.”

5. The Puritans tried to import African slaves, but they all died of the cold.

6. In 1639, Massachusetts declared a “Day Of Humiliation” to condemn “novelties, oppression, atheism, excesse, superfluity, idleness, contempt of authority, and trouble in other parts to be remembered”

7. The average family size in Waltham, Massachusetts in the 1730s was 9.7 children.

8. Everyone was compelled by law to live in families. Town officials would search the town for single people and, if found, order them to join a family; if they refused, they were sent to jail.

9. 98% of adult Puritan men were married, compared to only 73% of adult Englishmen in general. Women were under special pressure to marry, and a Puritan proverb said that “women dying maids lead apes in Hell”.

10. 90% of Puritan names were taken from the Bible. Some Puritans took pride in their learning by giving their children obscure Biblical names they would expect nobody else to have heard of, like 'Mahershalalhasbaz'. Others chose random Biblical terms that might not have technically been intended as names; “the son of Bostonian Samuel Pond was named "Mene Mene Tekel Upharsin Pond”. Still others chose Biblical words completely at random and named their children things like 'Maybe' or 'Notwithstanding'.

11. Puritan parents traditionally would send children away to be raised with other families, and raise those families’ children in turn, in the hopes that the lack of familiarity would make the child behave better.

12. In 1692, 25% of women over age 45 in Essex County were accused of witchcraft.

13. Massachusetts passed the first law mandating universal public education, which was called The 'Old Deluder Satan' Law in honor of its preamble, which began “It being one chief project of that old deluder, Satan, to keep men from the knowledge of the scriptures…”

14. Massachusetts cuisine was based around “meat and vegetables submerged in plain water and boiled relentlessly without seasonings of any kind”.

15. Along with the famous scarlet A for adultery, Puritans could be forced to wear a B for blasphemy, C for counterfeiting, D for drunkenness, and so on.

16. Wasting time in Massachusetts was literally a criminal offense, listed in the law code, and several people were in fact prosecuted for it.

17. This wasn’t even the nadir of weird hard-to-enforce Massachusetts laws. Another law just said “If any man shall exceed the bounds of moderation, we shall punish him severely”.

Thanks, Feliks. This was the famous (infamous) "City upon a Hill" that John Winthrop (one of Massachusetts Bay's principal founders) envisioned and which many Americans still extol. I compare the basic laws of the Massachusetts theocracy with the much more enlightened legal framework of Roger Williams’s Providence (later Rhode Island) in The First American Founder: Roger Williams and Freedom of Conscience. My analysis focuses on church-state separation and freedom of conscience and ends with Roger Williams’s death in 1683. I cite Albion’s Seed on some points.

Thanks, Feliks. This was the famous (infamous) "City upon a Hill" that John Winthrop (one of Massachusetts Bay's principal founders) envisioned and which many Americans still extol. I compare the basic laws of the Massachusetts theocracy with the much more enlightened legal framework of Roger Williams’s Providence (later Rhode Island) in The First American Founder: Roger Williams and Freedom of Conscience. My analysis focuses on church-state separation and freedom of conscience and ends with Roger Williams’s death in 1683. I cite Albion’s Seed on some points.With regard to enforcement of the Massachusetts laws, the magistrates had "minders" (like in the former Soviet Union and other totalitarian countries) who would inform the government (a mixed government of church and state) when anyone was not conforming to the strict regime.

As an eminent New England historian once put it, "The government of [seventeenth-century] Massachusetts, and of Connecticut as well, was a dictatorship, and never pretended to be anything else; it was a dictatorship, not of a single tyrant, or of an economic class, or of a political faction, but of the holy and regenerate." Perry Miller, Errand into the Wilderness (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1984), 143.

Agreed. It's hard to think of a dictatorship existing at any time in our land-of-the-free, but these communities clearly were of that sensibility. Imagine anyone after 1787 allowing such invasiveness! The Signers gave us our land-of-the-free.

Agreed. It's hard to think of a dictatorship existing at any time in our land-of-the-free, but these communities clearly were of that sensibility. Imagine anyone after 1787 allowing such invasiveness! The Signers gave us our land-of-the-free.

Feliks wrote: "Agreed. It's hard to think of a dictatorship existing at any time in our land-of-the-free, but these communities clearly were of that sensibility. Imagine anyone after 1787 allowing such invasivene..."

Feliks wrote: "Agreed. It's hard to think of a dictatorship existing at any time in our land-of-the-free, but these communities clearly were of that sensibility. Imagine anyone after 1787 allowing such invasivene..."Well, yes, except for slaves and Native Americans. Additionally, the later Bill of Rights (ratified in 1791) did not apply to state and local government until much later. Massachusetts and Connecticut continued their theocratic practices well into the nineteenth century, and some theocratic laws of various states lasted well into the twentieth century. Even today, religion and government are not fully separated in the United States.

I'm going to add some more background regarding the settlers which came under Hackett's study.

I'm going to add some more background regarding the settlers which came under Hackett's study.But for now, just a quick info-squirt. Been doing some armchair-research lately and stumbled upon an episode in Early America I can't recall, ever having heard about before.

When I was in grade school, it was dogma that Thomas Jefferson acquired the Louisiana Territory from the French in 1803. Right?

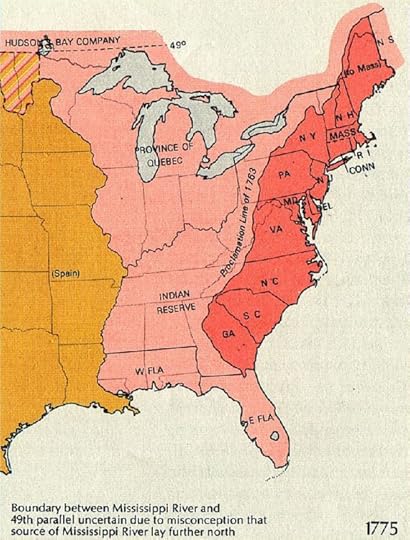

But then what on Earth was the 'Proclamation of 1763', just a few decades prior?

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Royal_P...

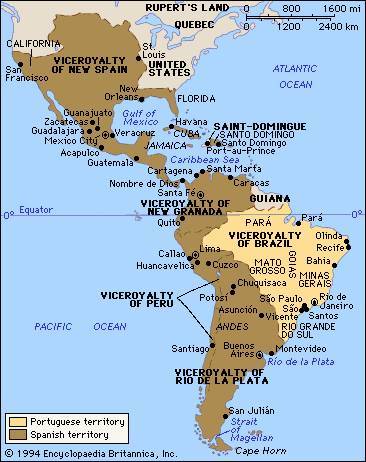

Apparently, France and Spain had been trading the North American heartland (the future USA) between them like Topps baseball cards. Just a few years prior to Jefferson's bargain.

Most of America was 'New Spain'.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Louisia...

Everything beyond a slender Mid-Atlantic DMZ of Native-American land we have Napoleon to thank for getting back from Spain to sell to us. How narrow a thing! Had to do with some sort of 'secret treaty' which let Spain save face.

Consider how much total American land-area Spain controlled:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spanish...

Might startling that Philip II had his hand on the entire western hemisphere, and fumbled it.

Apparently, the influx of wealth from the Americas, was too much for him to handle. He defaulted on his debts upwards of forty times during his splendid reign.

I just wrote a long post regarding the Proclamation of 1763 and the Louisiana Purchase, but I lost it when I tried to post it here, and I cannot recover it.

I just wrote a long post regarding the Proclamation of 1763 and the Louisiana Purchase, but I lost it when I tried to post it here, and I cannot recover it.The essential point is that Americans refused to comply with the Proclamation of 1763 by nevertheless invading American Indian lands beyond the Proclamation line. The Louisiana Purchase exacerbated this American incursion on Native lands.

For some reason, many Americans think that “freedom” means their right to physically harm others. The logical conclusions of such a view are that criminal law must be thrown out the window and the Hobbesian war of all against all must prevail. We see this notion of “freedumb” today, where many Americans refuse to comply with Covid mask-wearing and social-distancing requirements. It is a blatant violation of the bedrock libertarian principle that no one has a right to initiate force against another. Contemporary libertarians and anarchocapitalists have largely abandoned that principle with regard to individual action, but they insist upon it with regard to governmental action (thus opposing all taxes and governmental regulation). In truth, it should be the other way around. This is one of the themes I will develop in my forthcoming books on ethical and political philosophy.

*Wince* at the loss of a big chunk of text! Whew. I use 'Ditto' (free) clipboard manager. Whenever I'm typing something lengthy, I frequently 'select all' text and then copy it. Ditto then saves each version as I go along, in case the web browser or Word application suddenly crashes. :(

*Wince* at the loss of a big chunk of text! Whew. I use 'Ditto' (free) clipboard manager. Whenever I'm typing something lengthy, I frequently 'select all' text and then copy it. Ditto then saves each version as I go along, in case the web browser or Word application suddenly crashes. :(

Feliks wrote: "*Wince* at the loss of a big chunk of text like that. Whew. I use 'Ditto' (free) clipboard manager. Whenever I'm typing something lengthy, I frequently 'select all' text and then copy it; Ditto wil..."

Feliks wrote: "*Wince* at the loss of a big chunk of text like that. Whew. I use 'Ditto' (free) clipboard manager. Whenever I'm typing something lengthy, I frequently 'select all' text and then copy it; Ditto wil..."I usually compose longer posts in Word, and I frequently save the Word document to prevent it from disappearing. For some reason, I forgot to do that this morning. I had forgotten how temperamental Goodreads can be, since it hadn't happened to me for a long time. Never again!

Alan, I think I agree with your notion of "freedumb." But it seems to me that the "freedumb" see themselves as invoking the libertarian principle that no one has the right to force them to do anything. They seem to me to be a unintended parody of this principle.

Alan, I think I agree with your notion of "freedumb." But it seems to me that the "freedumb" see themselves as invoking the libertarian principle that no one has the right to force them to do anything. They seem to me to be a unintended parody of this principle. Maybe I misunderstand "freedumb."

Robert wrote: "Alan, I think I agree with your notion of "freedumb." But it seems to me that the "freedumb" see themselves as invoking the libertarian principle that no one has the right to force them to do anyth..."

Robert wrote: "Alan, I think I agree with your notion of "freedumb." But it seems to me that the "freedumb" see themselves as invoking the libertarian principle that no one has the right to force them to do anyth..."Right. That's exactly what they think, and that's where the "dumb" part comes in. It is criminal—literally and figurately.

My apologies for using a politically incorrect term in this context. "Dumb" does not, in its derivation from Middle English, mean stupid. Rather, I am using it in the derivation from the German dumm, which does mean stupid, as in dummkopf. Still, the conflation of the meanings in ordinary American speech has not been welcome to those who have a medical condition corresponding to the Middle English derivation. I would normally not use “dumb” in the German sense, but here the homonym cries out for such usage because it is so appropriate.

re: 'medical condition', do you mean the speech impediment? If so, I can confirm that the deaf community has long since abandoned that term; simply because the principle is that anyone who cannot hear also cannot speak. So it was always redundant. They do understand that outsiders occasionally still use it due to unfamiliarity with deafness; and they aren't quick to take offense over it.

re: 'medical condition', do you mean the speech impediment? If so, I can confirm that the deaf community has long since abandoned that term; simply because the principle is that anyone who cannot hear also cannot speak. So it was always redundant. They do understand that outsiders occasionally still use it due to unfamiliarity with deafness; and they aren't quick to take offense over it.

Feliks wrote: "re: 'medical condition', do you mean the speech impediment? If so, I can confirm that the deaf community has long since abandoned that term; simply because the principle is that anyone who cannot h..."

Feliks wrote: "re: 'medical condition', do you mean the speech impediment? If so, I can confirm that the deaf community has long since abandoned that term; simply because the principle is that anyone who cannot h..."Yes, I mean the inability to speak. In my observation, however, I note that some people who are even mostly deaf are able to learn how to speak, often with the use of hearing aids or surgery. My first wife was one of these individuals. Of course, they probably cannot learn how to speak until they have appropriate hearing aids or surgery.

Also, is it not true that some people who can hear cannot speak? I'm not at all an expert on this, but I recall reading something about it long ago.

Also, is it not true that some people who can hear cannot speak? I'm not at all an expert on this, but I recall reading something about it long ago.I seem to recall that Einstein did not say much in his early childhood, which gave rise to my own joke: "Einstein didn't say anything until one day he came out with "E = mc2."

It's been a while since I gave it any thought myself. All I can say is that I seem to recall this was one of the first tenets impressed upon me when I was training to be an interpreter. ASL was my first language in college. They told us "deaf and dumb do not go together". Similarly "deaf-mute". We were taught to divorce these conjoined terms. Maybe the 'missing middle' in my recollection is this: if you are born deaf, you may be able to make sounds; but sounds incoherent to others? Suffice to say there's deep connections between hearing, speaking, and reading; therefore literacy is also an issue for the deaf.

It's been a while since I gave it any thought myself. All I can say is that I seem to recall this was one of the first tenets impressed upon me when I was training to be an interpreter. ASL was my first language in college. They told us "deaf and dumb do not go together". Similarly "deaf-mute". We were taught to divorce these conjoined terms. Maybe the 'missing middle' in my recollection is this: if you are born deaf, you may be able to make sounds; but sounds incoherent to others? Suffice to say there's deep connections between hearing, speaking, and reading; therefore literacy is also an issue for the deaf.Einstein joke: vaudeville lives again!

Feliks wrote: "It's been a while since I gave it any thought myself. All I can say is that I seem to recall this was one of the first tenets impressed upon me when I was training to be an interpreter. ASL was my ..."

Feliks wrote: "It's been a while since I gave it any thought myself. All I can say is that I seem to recall this was one of the first tenets impressed upon me when I was training to be an interpreter. ASL was my ..."Thank you for the information.

Unrelated to last six msgs:

Unrelated to last six msgs: I sometimes think the early Americans are more easy to relate to than it would at first appear. They seem strangely familiar. Many of them were looking for new home, new surroundings; packing-up- their-things-and-heading-out-in-search-of-a-new life. This is very modern.

I also like how, it was not often that these proto-Americans were not fighting each other. That of course is unlike today when everyone's neighbor is their enemy; and no one sees eye-to-eye. The early Americans were usually united against the British or the French or the Spanish or (unfortunately) the First Nations peoples. I'm speaking broadly, but nevertheless it is refreshing and charming to follow --through the pages of our historians--our forebears struggling shoulder-to-shoulder.

Feliks wrote: "Unrelated to last six msgs:

Feliks wrote: "Unrelated to last six msgs: I sometimes think the early Americans are more easy to relate to than it would at first appear. They seem strangely familiar. Many of them were looking for new home, n..."

They were, at least in New England, united against heretics, i.e., anyone who did not accept their particular version of Christianity. Quakers, for example, were tortured and executed. Ingroup-outgroup behavior. When Roger Williams established Providence and Rhode Island, the other New England colonies ganged up on RI and tried to conquer them and make them conform to the strict Puritan theocracy. It was not a pretty picture. There was a lot of international politics involved, as the various factions tried to influence the governmental authorities in England to grant them control of RI.

Another one of the four 'British folkway groups' which (hypothetically) wielded an influence in the development of US Demographics: the English 'Cavaliers'.

Another one of the four 'British folkway groups' which (hypothetically) wielded an influence in the development of US Demographics: the English 'Cavaliers'.Massachusetts Puritans fled England in the 1620s partly due to oppression by the king and his nobles. In the 1640s, Puritans under Oliver Cromwell rebelled, took over the English government, and killed the king.

The original Jamestown settlers (1607) had mostly died of disease. Nevertheless, when the British nobility (aka, these 'Cavaliers' of southern England) found themselves on the run, they made Virginia a haven where they could maintain their social supremacy.

As late as 1775, every member of Virginia’s twelve-member royal council was descended from a councilor who had originally served in 1660.

Each of these aristocratic landowners ruled their new estates with an iron hand. The gender ratio was 4:1 in favor of men. Women were treated as chattels; many even brought there by kidnap.

The problem was that the tens of thousands of indentured servants the Royalists brought with them as part of their system of manorial labor, began dying out.

Europeans didn't adapt well to the warm climate of Virginia. Worker mortality was high from malaria, typhoid fever, amoebiasis, and dysentery.

The aristocrats started importing black slaves according to the Caribbean model; thus the stage was set for the antebellum South.

Interesting Cavalier Facts:

Interesting Cavalier Facts:1. Three-quarters of 17th-century Virginian children lost at least one parent before turning 18.

2. Cousin marriage was an important custom that helped cement bonds among the Virginian elite, and “many an Anglican lady changed her condition but not her name”.

3. In Virginia, women were sometimes (un-ironically) called “breeders”; English women were sometimes referred to as “She-Britons”.

4. Early Virginia didn’t have many large towns. The Chesapeake Bay was such a giant maze of rivers and estuaries and waterways that there wasn’t much need for land transport hubs. Instead, the unit-of-settlement was the plantation, which consisted of an aristocratic planter, his wife and family, his servants, his slaves, (and numerous guests who hung around and mooched-off-him, in accordance with the 'ancient custom of hospitality').

5. Virginian society considered everyone who lived in a plantation home to be a kind of “family”, with the aristocrat both as the literal father and as a sort of 'abstracted patriarch' with complete control over his domain.

6. Virginia Governor William Berkeley probably would not be described by moderns as ‘strong on education’. He said in a speech that “I thank God there are no free schools nor printing [in Virginia], and I hope we shall not have these for a hundred years, for learning has brought disobedience, and heresy, and sects into the world, and printing has divuldged them, and libels against the best government. God keep us from both!”

7. Virginian recreation mostly revolved around hunting and bloodsports. Great lords hunted deer, lesser gentry hunted foxes, indentured servants had a weird game in which they essentially draw-and-quartered geese, young children “killed and tortured songbirds”. Also: “at the bottom of this hierarchy of bloody games were male infants who prepared themselves for the larger pleasures of maturity by torturing snakes, maiming frogs, and pulling the wings off butterflies. Thus, every red-blooded male in Virginia was permitted to slaughter some animal or other, and the size of his victim was proportioned to his social rank.”

8. “In 1747, an Anglican minister named William Kay infuriated the great planter Landon Carter by preaching a sermon against pride. The planter took it personally and sent his [relations] and ordered them to nail up the doors and windows of all the churches in which Kay preached.”

9. Our word “condescension” comes from a ritual attitude that leading Virginians were supposed to display to their inferiors. Originally condescension was supposed to be a polite way of showing respect those who were socially inferior to you; our modern use of the term probably says a lot about what Virginians actually did with it.

10. Virginia had a rule that if a female indentured servant became pregnant, a few extra years could be added on to their indenture, supposedly because 'they would be working less hard during their pregnancy and child-rearing' (so it wasn’t fair to their owner). Virginian aristocrats would consequently molest some of their female servants, then add a 'penalty term' on to their indenture for becoming pregnant.

Happened to be reading up on this Roman statesman this weekend: "Fabius Maximus." He saved ancient Rome from Hannibal's forces.

Happened to be reading up on this Roman statesman this weekend: "Fabius Maximus." He saved ancient Rome from Hannibal's forces.https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quintus...

I did not know --but found out --that our George Washington is sometimes praised as 'the American Fabius' for adopting the "Fabian strategy" of delaying and harassing a larger enemy.

As a schoolchild I always found GW to be one of the most difficult of our founders to "get-a-feel-for", personality-wise. Even though I was fed --as all youngsters are --swathes of information on the man, even though his face is revealed to us in oils and coins, and even though his name bedecks our streets and ships, our bridges and cities.

I know that modern biographers laud his sagacity, his perspicacity, etc. and --wile I have never dug too deeply into his life story --I tend to believe he possessed mental gifts in great measure. I'm glad he led our country's fight for independence, and I think he did a great job setting us on a path to stable nationhood.

But I never got the idea from elementary school textbooks that he was this kind of general, this "guerrilla leader" style of leader; fighting a 'sneaky war' of sabotage and interdiction behind-enemy-lines.

School textbooks always seemed to present him in the opposite light --standing up straight, tall, and resolute, always at the head of his men, always gazing staunchly forward at opposing British infantry. 'Crossing the Delaware', etc.

I wonder whether it would ever change American sensibilities if the more accurate view was related.

Maybe this belongs under another topic, but lately I'm wondering: what were the most widely read books in America, during the 1700s and 1800s? What were the books found in typical everyday American households? There are discrepancies depending on what authority one refers to.

Maybe this belongs under another topic, but lately I'm wondering: what were the most widely read books in America, during the 1700s and 1800s? What were the books found in typical everyday American households? There are discrepancies depending on what authority one refers to. There are lists of popular works, and there are lists of 'important milestone' works, but I can't find a definitive list of what people actually bought, ranked by sales figures.

I have a few titles pinned down with relative certainty, but it's tough because it was that strange era of circulars and pamphlets, circulars and town-criers.

I think it's a subject worth knowing more about. What did people actually read?

Feliks wrote: "Maybe this belongs under another topic, but lately I'm wondering: what were the most widely read books in America, during the 1700s and 1800s? What were the books found in typical everyday American..."

Feliks wrote: "Maybe this belongs under another topic, but lately I'm wondering: what were the most widely read books in America, during the 1700s and 1800s? What were the books found in typical everyday American..."Without question, the Bible was number 1. Most families would have had the Bible and nothing else. Only in the upper middle and upper classes would one find private libraries, e.g. the Adamses (father and son), Jefferson, Madison, Washington, and others among the founding generation. My guess is that the reading level went down during the nineteenth century, but that's just a speculation on my part.

My own parents, who were middle class, owned only a Bible and a handful of other books (I remember Arthur Koestler's Darkness at Noon, but my parents were not Commies!) that they had somehow acquired over the years (I don't know how, and I don't remember the other titles). Even worse, the town in which I grew up didn't even have a bookstore. The public and school libraries were my main sources of books until I went off to college. In my last year or two of high school, a local drug store had a rack of paperback books that included many philosophical classics, such as John Stuart Mill's Utilitarianism, which I bought at that time and still have. I also bought Paul Tillich's The Courage to Be and a few other such books off that rack. It was like manna from heaven for me, even though I would now disagree with things in all these books.

Arthur Koestler is certainly an odd name to find in a Minnesota home. Even worse: a town with no bookstore! My goodness.

Arthur Koestler is certainly an odd name to find in a Minnesota home. Even worse: a town with no bookstore! My goodness. Anyway, bravo. You sure showed them where the high road can lead to.

Dovetailing with #2 and #21, above.

Dovetailing with #2 and #21, above.Another of the four prominent waves of American colonists imbued with United Kingdom origins, were the Quakers. Alan, you're likely already very familiar with the Quakers but maybe others are not. And since I've already embarked down this thread with discussion of two of the other folkways groups cited in Fischer's "Albion's Seed" then, I may as well add the remaining two.

Of all the British-based American colonists, the Quakers seem remarkably modern and enlightened. Not so very different than hip, sensitive, ordinary folks in our era. This is not borne out in root-level detail; after all they were without a doubt, a sort of religious "cult". But at arm's length, at a glance --the Quakers aren't bad at all. By and large, they're nice guys as far as the Seventeenth Century goes.

Quakers were founded by a weaver’s son named George Fox. He believed people were basically good and had an Inner Light that connected them directly to God without a need for priesthood, ritual, Bible study, or self-denial. Fox felt that people just needed to listen to their consciences and be nice.

And, since everyone was equal before God, there was no point in holding up distinctions between lords and commoners: Quakers addressed everybody as “Friend”.

Despite the Quakers being among the most persecuted sects of their era, they developed an insistence on tolerance and freedom of religion which (unlike the Puritans) they stuck to even when shifting fortunes put them on top.

They believed in pacifism, equality of the sexes, racial harmony, and a bunch of other things which seem pretty advanced today, let alone in 1650.

England’s top Quaker in the late 1600s was William Penn. Penn is universally known to Americans as, “that guy Pennsylvania is named after” but actually was a larger-than-life 17th century superman. Born to the nobility, Penn distinguished himself early on as a military officer; he was known for beating legendary duelists in single combat and then sparing their lives with sermons about how murder was wrong. He gradually started having mystical visions, quit the military, and converted to Quakerism.

Like many Quakers, Penn was arrested for blasphemy; unlike many Quakers, they couldn’t make the conviction stick; in his trial he “conducted his defense so brilliantly that the jurors refused to convict him even when threatened with prison themselves, [and] the case became a landmark in the history of trial by jury.”

When the state finally found a pretext on which to throw Penn in prison, he spent his incarceration composing, “one of the noblest defenses of religious liberty ever written”, conducting a successful mail-based courtship with England’s most eligible noblewoman, and somehow gaining the personal friendship and admiration of King Charles II.

Upon his release, the King liked him so much that he gave him a large chunk of the Eastern United States on a flimsy pretext of repaying a family debt. Penn didn’t want to name his new territory Pennsylvania (he recommended just “Sylvania”), but everybody else overruled him and Pennyslvania it was. The grant wasn’t quite the same as the modern commonwealth's boundaries today, but it was a generous chunk of land centered around the obviously-named-by-Quakers city of "Philadelphia".

William Penn's "Quaker refuge" mandated universal religious toleration, a total ban on military activity, and a government based on checks-and-balances that would, “leave myself and successors no power of doing mischief, that the will of one man may not hinder the good of a whole country”.

His recruits – about 20,000 people in total – were Quakers from the north of England, many of them minor merchants and traders. They were joined by several German sects close enough to Quakers that they felt at home there; these became the ancestors of (among other groups) the Pennsylvania Dutch, Amish, and Mennonites.

Interesting Quaker Facts:

1. Fischer argues that the Quaker ban on military activity within their territory would have doomed them in most other American regions, but by extreme good luck the Indians in the Delaware Valley were almost as peaceful as the Quakers. As usual, at least some credit goes to William Penn, who taught himself Algonquin so he could negotiate with the Indians in their own language.

2. The Quakers’ marriage customs combined a surprisingly modern ideas of romance, with extreme bureaucracy. The wedding process itself had sixteen stages, including “ask parents”, “ask community women”, “ask community men”, “community women ask parents”, and “obtain a certificate of cleanliness”. William Penn’s marriage apparently had forty-six witnesses to testify to the good conduct and non-relatedness of both parties.

3. Possibly related: 16% of Quaker women were unmarried by age 50, compared to only about 2% of Puritans.

4. Quakers promoted gender equality, including the (at the time scandalous) custom of allowing women to preach (condemned by the Puritans as the crime of “she-preaching”).

5. But they were such prudes about sex that even the Puritans thought they went too far. Pennsylvania doctors had problems treating Quakers because they would “delicately describe everything from neck to waist as their ‘stomachs’, and anything from waist to feet as their ‘ankles'”.

6. Quakers had surprisingly modern ideas about parenting, basically sheltering and spoiling their children at a time when everyone else was trying whip the Devil out of them.

7. William Penn wrote about thirty books defending liberty of conscience throughout his life. The Quaker obsession with the individual conscience as the work of God helped invent the modern idea of conscientious objection.

8. Quakers were heavily (and uniquely for their period) opposed to animal cruelty. When foreigners introduced bullbaiting into Philadelphia during the 1700s, the mayor bought a ticket supposedly as a spectator. When the event was about to begin, he leapt into the ring, personally set the bull free, and threatened to arrest anybody who stopped him.

9. On the other hand, they were also opposed to other sports for what seem like kind of random reasons. The town of Morley declared an anathema against foot races, saying that they were “unfruitful works of darkness”.

10. The Pennsylvania Quakers became very prosperous merchants and traders. They also had a policy of loaning money at low- or zero- interest to other Quakers, which let them outcompete other, less religious businesspeople.

11. They were among the first to replace the set of bows, grovels, nods, meaningful looks, and other British customs of acknowledging rank upon greeting with a single rank-neutral equivalent – the handshake.

12. Pennsylvania was one of the first polities in the western world to abolish the death penalty.

13. The Quakers were lukewarm on education, believing that too much schooling obscured the natural Inner Light. Fischer declares it “typical of William Penn” that he wrote a book arguing against reading too much.

14. The Quakers not only instituted religious freedom, but made laws against mocking another person’s religion.

15. In the late 1600s as many as 70% of upper-class Quakers owned slaves, but Pennsylvania essentially invented modern abolitionism. Although their colonial masters in England forbade them from banning slavery outright, they applied immense social pressure and by the mid 1700s less than 10% of the wealthy had African slaves. As soon as the American Revolution started, forbidding slavery was one of independent Pennsylvania’s first actions.

Credits: salient points condensed here from Scott Alexander's book review.

Thanks, Feliks, for the additional summary from Fischer's book.

Thanks, Feliks, for the additional summary from Fischer's book.Another fact: The Quakers were not popular with the U.S. Founders, because they adhered to their pacifism at the time of the American Revolution. Some thought they were disloyal. I discuss that tension at some length in my book on Roger Williams.

I distinctly recall that Quakers were among the most visible groups opposing the Vietnam War. I happened to be acquainted at that time with a graduate student who was a Quaker. Although she was not herself an antiwar activist, she did follow her religion, which by that time was a lot more "liberal" than the version practiced in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

H'mm! I did not know that factoid re: Vietnam.

H'mm! I did not know that factoid re: Vietnam.Something else intriguing about Quakers: their sharp business practices. Of all the American immigrants, this "pacifist religious cult" spearheaded many canny ins-and-outs of the rampant American mercantilism we know so well today. They were forthright in their pursuit of commerce. They made it a respected civic virtue, one of the hallmarks of our national character. Go figure.

Feliks wrote: " Something else intriguing about Quakers: their sharp business practices. Of all the American immigrants, this "pacifist religious cult" spearheaded many canny ins-and-outs of the rampant American mercantilism we know so well today. They were forthright in their pursuit of commerce. They made it a respected civic virtue, one of the hallmarks of our national character. Go figure.”

Feliks wrote: " Something else intriguing about Quakers: their sharp business practices. Of all the American immigrants, this "pacifist religious cult" spearheaded many canny ins-and-outs of the rampant American mercantilism we know so well today. They were forthright in their pursuit of commerce. They made it a respected civic virtue, one of the hallmarks of our national character. Go figure.”Yes, between the Puritans and the Quakers, it’s no wonder that the capitalist mentality became dominant in the United States. See the Wikipedia discussion of Weber’s The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Pro.... (By the way, I don’t entirely agree with Weber’s account of Ben Franklin, who was not religious in any conventional sense; Weber missed Franklin’s deep and witty irony.)

the strange backstory of 'West Ford'

the strange backstory of 'West Ford'http://www.westfordlegacy.com/taxonom...

http://gumspringsmuseum.blogspot.com/

http://www.mtwoodleymanor.com/about-m...

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/West_Ford

Note the unusual oil paintings of G Wash as a young man. He wasn't an unhandsome fellow

Feliks wrote: "the strange backstory of 'West Ford'

Feliks wrote: "the strange backstory of 'West Ford'http://www.westfordlegacy.com/taxonom...

http://gumspringsmuseum.blogspot.com/

http://www.mtwoodleymanor.com/about-m...

https://en.wikipedia...."

I didn't know about West Ford. Thank you for the information.

Who was the first American citizen executed by the American government for the crime of treason against The United States?

Who was the first American citizen executed by the American government for the crime of treason against The United States?Would you assume that unhappy individual to have been Benedict Arnold? That's what I myself would have said. Arnold was an infamous rogue. His crimes were scandalous.

But no, it is not he, (says Wikipedia).

Apparently, it was ...(view spoiler).

Greetings Feliks and Alan, Hackett Fishers work is remarkable and so have just started his new work, “African Founders - How Enslaved People Expanded American Ideals”. This work obviously expands on his thesis in Albion’s Seed to include the transformative and more than a little minimized impact of African slaves on the colonial and post revolutionary political culture of America. I’ll keep my updates and hopefully write a review when completed

Greetings Feliks and Alan, Hackett Fishers work is remarkable and so have just started his new work, “African Founders - How Enslaved People Expanded American Ideals”. This work obviously expands on his thesis in Albion’s Seed to include the transformative and more than a little minimized impact of African slaves on the colonial and post revolutionary political culture of America. I’ll keep my updates and hopefully write a review when completed

Charles wrote: "Greetings Feliks and Alan, Hackett Fishers work is remarkable and so have just started his new work, “African Founders - How Enslaved People Expanded American Ideals”. This work obviously expands o..."

Charles wrote: "Greetings Feliks and Alan, Hackett Fishers work is remarkable and so have just started his new work, “African Founders - How Enslaved People Expanded American Ideals”. This work obviously expands o..."Thank you, Charles. I was unaware of this recent book by David Hackett Fischer and have now put it on my "To Read" list.

toothsome article about conspiracy mania in the 1800s

toothsome article about conspiracy mania in the 1800sWashington Post --not sure whether it is visible to everyone --but fun reading

https://www.washingtonpost.com/outloo...

Feliks wrote: "toothsome article about conspiracy mania in the 1800s

Feliks wrote: "toothsome article about conspiracy mania in the 1800sWashington Post --not sure whether it is visible to everyone --but fun reading

https://www.washingtonpost.com/outloo......"

Good one. I wasn't aware of this.

Gordon S. Wood’s July 2, 2024 essay “What Explains the Genius of the American Founders?”

Gordon S. Wood’s July 2, 2024 essay “What Explains the Genius of the American Founders?”The author of this essay (https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinio...) is Gordon S. Wood, an eminent historian. Although I don't agree with everything he has written, I have always been impressed by the breadth and depth of his scholarship. His book The Creation of the American Republic, 1776-1787 is a masterpiece. His present essay is a distillation of decades of study and writing about the founding era. (As a result of my Washington Post subscription, the foregoing link can be accessed without charge for fourteen days, notwithstanding the usual Washington Post paywall.)

The medieval European device colloquially referred to as a 'ducking stool' --

The medieval European device colloquially referred to as a 'ducking stool' --https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ducking...

and the 'skimmington' (a type of public parade)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charivari

--both had brief tenure in early American society, apparently. The notorious 'scarlet letter' kind of shaming, depicted so well by author Nathaniel Hawthorne.

But I wonder whether the principles of public humiliation are truly an antiquated urge --or if they have merely been replaced by more modern media and newsmedia?

Just musing out loud.

For how seventeenth-century Massachusetts Bay used such procedures against Quakers, see the following excerpt from page 240 of my book The First American Founder: Roger Williams and Freedom of Conscience (endnotes omitted):

For how seventeenth-century Massachusetts Bay used such procedures against Quakers, see the following excerpt from page 240 of my book The First American Founder: Roger Williams and Freedom of Conscience (endnotes omitted): Quakers began arriving in New England in 1656. Massachusetts Bay considered them heretics and passed numerous laws against them, including whippings, fines, imprisonments, mutilations, and banishments. When those laws, which were severely enforced, failed to stem the immigration tide, Massachusetts provided that Quakers who returned after being banished would be put to death. As a result, four Quakers, including one woman, were executed between 1659 and 1661.

Popular discontent with the executions along with anticipated corrective action by the restored King Charles II resulted in Massachusetts passing, on May 22, 1661, legislation that became known as the Vagabond Act or the Cart and Whip Act. Under this law, all those found to be “wandering” Quakers (defined to mean virtually all Quakers) were to be “stripped naked from the middle upwards, & tied to a carts tayle, & whipped through the towne, & from thence immediately conveyed to the constable of the next towne towards the borders of our jurisdiction . . . & so from connstable to connstable till they be conveyed through any the outward most townes of our jurisdiction.”

Hi Alan (& everyone)

Hi Alan (& everyone)This is a rather strange assertion I'm about to make. It may be totally unfounded; I don't quite know as I haven't pondered it through yet.

And the War of 1812 is not something which crosses my mind very frequently these days.

But I'm thinking about how most of the war was fought in the north --and how, in that northern campaign, America was very soundly thrashed by the Brits. Humiliating defeat after defeat.

Finally --though the Treaty of Ghent was signed several days before --America wins the spectacular Battle of New Orleans. A very satisfying final round; although the war officially closed in rather a stalemate, or 'draw'.

The war didn't continue, but if it had, the Brits would've probably withdrawn, finding that some regions of our nation are no pushover.

So --of all the least likely saviors --wasn't it the American South which preserved American military pride? The swampers and the water-rats of the bayou country?

Is it unfair to put the episode in these admittedly simplistic terms?

We know that 1812 propelled several men to fame. Jackson, Harrison, Johnson, Taylor, Tyler, Perry, Winfield Scott.

But I wonder why the South never gets any credit for saving the nation from ignominy?

Did the later War Between the States invoke such bitterness that the Secessionist States lost all such respect?

Feliks wrote: "Hi Alan (& everyone)

Feliks wrote: "Hi Alan (& everyone)This is a rather strange assertion I'm about to make. It may be totally unfounded; I don't quite know as I haven't pondered it through yet.

And the War of 1812 is not someth..."

It's been a long time since I read about the battlefield history of the War of 1812, and I don't now recall the details. I don't know whether it is accurate to say that that the South "preserved American pride." It's true that the Southern War Hawks (Calhoun et al.) got us into the war, but the major Southern victory (New Orleans) occurred, as you observe, after the peace treaty was signed. That success propelled Andrew Jackson (one of Trump's heroes) to the White House, which is a dubious accomplishment considering his genocide of Native Americans (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trail_o...).

Interesting fact: The US tried to "liberate" Canada by invading it during the War of 1812, but the Canadians weren't interested, just as they weren't interested when the US invaded them in the War for Independence and just as they are not interested now in being annexed by King Trump. To quote Bob Dylan, "When will they [we] ever learn?"

Rumor has it that Ken Burns is coming out with a new documentary series on the American War for Independence.

Rumor has it that Ken Burns is coming out with a new documentary series on the American War for Independence.https://www.pbs.org/kenburns/the-amer...

Alan E, we'll be keen to hear your criticisms!

Feliks wrote: "Rumor has it that Ken Burns is coming out with a new documentary series on the American War for Independence.

Feliks wrote: "Rumor has it that Ken Burns is coming out with a new documentary series on the American War for Independence.https://www.pbs.org/kenburns/the-amer...

Alan E, we'll be keen to hear yo..."

I look forward to watching it. Ken Burns certainly has his heart in the right place, and his work is usually very good. If I have any criticisms, they will probably be very minor. I admire his dedication. Would that more people in his world were as conscientious.

William A. Alcott of Massachusetts. Whew.

William A. Alcott of Massachusetts. Whew.They sure don't make Americans like this anymore. [Or, do they? Somewhere?]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William...

https://www.goodreads.com/author/show...

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/3...

Alcott has numerous titles on Goodreads; and I was almost going to cite him under one of the group's two, 'Education' topics.

Reason: Alcott was an early influence on our education system as well as one of the most prolific authors of his heyday.

But he doesn't seem to fit under either 'Libraries' or 'Civics'.

Ah well. I'm merely calling him to the attention of this body, because he was certainly a character. Good grief.

Alan E., --having worked in Education yourself --you may get a kick out of this.

Been thinking about who gets blame or credit over the War of 1812.

Been thinking about who gets blame or credit over the War of 1812.Traditionally the US Navy is celebrated (as against the Army) for both squadron actions on the lakes and frigate actions on the high seas. British politicians had dismissed the tiny American fleet as consisting of “fir-built frigates with bits of bunting at the masthead, manned by outlaws and bastards.” The 44-gun American frigates knocked British 36 or 38 gun counterparts to so much kindling wood: in fact they burned the British hulls as beyond safe sailing to an American port.

Of course, with Napoleon out of the way, the Royal Navy was at last free to transfer ships of the line to the American coast.

And the conclusion of the Peninsular War ended the odd arrangement of allowing American ships to deliver grain to Spain and Portugal, well beyond British resources. Which had helped maintain the American economy….

Ian wrote: "Been thinking about who gets blame or credit over the War of 1812.

Ian wrote: "Been thinking about who gets blame or credit over the War of 1812.Traditionally the US Navy is celebrated (as against the Army) for both squadron actions on the lakes and frigate actions on the h..."

The War of 1812 was one of those episodes of history where no matter what the president (Madison, in this case) and Congress did, or did not do, there was not going to be much of a positive outcome. When the smoke was cleared from the fighting, the parties were basically back to where they were at the beginning. It is a sad commentary on the human condition as exemplified in international politics. More recent examples include Vietnam, Afghanistan, and Iraq.

Bradford Perkins’ Prologue to War: England and the United States, 1805-1812 is a detailed analysis of mainly diplomatic disputes, but with a good deal on American and British “public opinion,” meaning mainly views of the political class.

Bradford Perkins’ Prologue to War: England and the United States, 1805-1812 is a detailed analysis of mainly diplomatic disputes, but with a good deal on American and British “public opinion,” meaning mainly views of the political class.Unlike some historians, Perkins does not confuse Porcupine’s Gazette, a British propaganda arm, with a source for American policy. (“Peter Porcupine” was a pseudonym of William Cobbett in his chauvinistic English mode — never mind that he had found sanctuary in the US from charges of sedition at home)

"Rules of Civility and Decent Behavior in Company and Conversation"

"Rules of Civility and Decent Behavior in Company and Conversation"The book that shaped George Washington's character.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rules_o...

https://www.mountvernon.org/library/d...

https://washingtonpapers.org/document...