Questionable: Red Herrings and Gotchas

Sure Thing asked

Sure Thing asked

“With mysteries, what about red herrings and misdirection in terms of plot? How far is too far that it may end up being a gotcha?”

Spoiler Warning: The endings of The Sixth Sense and The Murder of Roger Ackroyd are revealed below.

Let’s backtrack to the underlying assumption here which is that readers must believe in the authority in the text; that is, that the success of a story depends on the feeling that the writer knows what she is doing and sees the reader as a partner to be treated fairly, not a mark to duped. And that basically comes down to asking if the reversal/surprise/red herring/whatever is in the narrative as a legitimate part of the story or if it’s there to provoke and trick the reader.

One of the most lauded reversals in film comes at the end of The Sixth Sense when the little boy tells the point-of-view character that he’s dead. This is pretty universally regarded as a great surprise ending because it’s completely fair: if you watch the movie again, the clues are all there, but the fact is never onscreen because the point-of-view character thinks he’s still alive. But another reason for its impact is that this information is important; it’s not there just to be a surprise ending, it changes the entire story so that when you watch the movie again, you’re not seeing a little boy traumatized by his ability to see and speak with the dead being helped by a kind psychologist, you’re seeing a little boy traumatized by his ability to see and speak with the dead being helped by a kind, dead psychologist. The reversal at the end actually makes the movie better by making the child’s situation even more traumatic and his journey to stability even more poignant.

One of the most contested reversals in detective fiction is in The Murder of Roger Ackroyd because of its revelation at the end that the narrator is the murderer. This is not because the clues aren’t there throughout the story; in that sense the story is fair. It’s because the first-person point-of-view character knows he did the murder and skips over that part as he narrates the story. He tells of talking with Ackroyd in his library when Ackroyd gets a letter. He asks Ackroyd to read while he’s there, and Ackroyd refuses. And then . . .

“The letter had been brought in at twenty minutes to nine.

It was just on ten minutes to nine when I left him, the letter still unread. I hesitated with my hand on the door handle, looking back and wondering if there was anything I had left undone. I could think of nothing. With a shake of the head I passed out and closed the door behind me.”

See that paragraph break? That where he murdered Ackroyd. He (and Christie) deliberately leave out information that he would have been thinking about in order to dupe the reader. The reversal doesn’t cast the narrative in a new light or make it better. It’s a trick, not an extra layer of story. Christie tried to finesse her trickery by making the story a manuscript that the murderer was writing as the one case that Hercule Poirot never solved, which of course Poirot solves. So faced with ruin, he ends his manuscript with this confession (and suicide):

“I am rather pleased with myself as a writer. What could be neater, for instance, than the following:

‘The letters were brought in at twenty minutes to nine. It was just on ten minutes to nine when I left him, the letter still unread.

I hesitated with my hand on the door handle, looking back and wondering if there was anything I had left undone.’

All true, you see. But suppose I had put a row of stars after the first sentence! Would somebody then have wondered what exactly happened in that blank ten minutes?”

The problem with that is that even though it’s clever and fair since the narrative is being written by a sociopath, it still came across as a gotcha to many readers. And in readership as in so much else, perception is reality. They felt swindled and Christie’s rationale there at the end (and it’s hers, not just the murderer’s) doesn’t make up for the cheat.

So one way to think of it is that a reversal is “I surprised you and the surprise made the story new and better,” and a bad reversal/gotcha is “I duped you.”

Which brings us to Sure Thing’s question: What about red herrings?

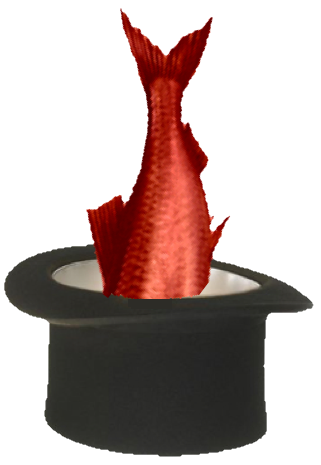

Red herrings in a story are misdirections, analagous to a magician directing the audience to look at his glamorous assistant while he’s putting the rabbit in the hat. There is nothing stopping the audience from seeing the rabbit go into the hat, they’ve just been given two choices and they’re going for the one that’s bigger and better lit. Once they realize what’s going on, they can catch the magician’s act again, refuse to look away, and see that the rabbit was clearly there from the beginning. They play fair with viewer/reader because the truth is always on the page.

Red herrings go bad when the writer unfairly or illogically withholds crucial information. “We did a complete background check on that guy, but forgot to mention that he has a twin brother because it didn’t seem important.” No.

That means your red herring is fine if it’s part of the entire package of information the reader needs to solve the mystery. If your red herring is only that lovely color because important information is missing, it’s bad fish.

As a writer, you’re not required to say, “Hey, LOOK OVER HERE, this is IMPORTANT,” but you are required to put the information on the page if it’s something that would be known to the point-of-view character or would come to light in the logical progression of story events. You can gesture to the glamorous clue that’s better lit as a red herring, but you also have to put the rabbit in the hat on the page or it’s a gotcha.

The post Questionable: Red Herrings and Gotchas appeared first on Argh Ink.