Carpe Noctem Chapbook Interview With Jessica Walsh

ELJ Editions THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…

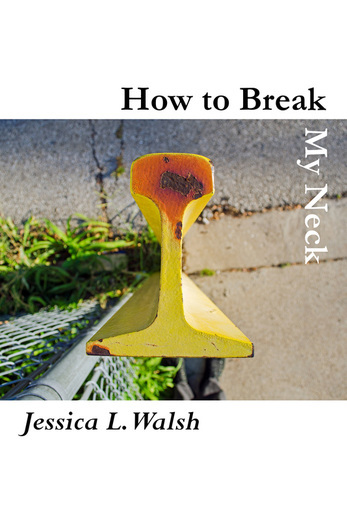

ELJ Editions THINGS WE’RE DYING TO KNOW…Let’s start with the book’s title and your cover image. How did you choose each? And, if I asked you to describe or sum up your book, what three words immediately come to mind?

I was watching a true crime show, the kind with horrible re-enactments. The man very gently came up behind a woman, and for a moment he resembled a lover about to kiss her neck. But of course that’s not what happened. He broke her neck. And I was deeply bothered by how much the vulnerability of love resembled the risk of violence. That’s how it is, right? If I let someone into my life, that person is always on the line between loving and destroying me. So the poetry is my bare neck, I suppose, and I’m putting it out there for anyone to hold or break.

The cover image is by a colleague of mine, a wonderful artist and genuinely good human, Charles Roderick. I went to his work right away. The image of the rusted beam from his Platform series,conjured that mix of vulnerability and beauty that I wanted to capture in the book.

Three words I’d use to describe my book: rusty jilted brides. From “More Like Me.” Not really sure why, but that’s what keeps coming up.

What were you trying to achieve with your book? Tell us about the world you were trying to create, and who lives in it.

Flannery O’Connor wrote in “A Good Man is Hard to Find” about a woman who transcends her failings in the moment before she’s executed. The man who kills her says she would’ve been a good woman “if it had been somebody there to shoot her every minute of her life.” My book tries to stay in that moment when we’re at our end but also at our best. I use last words as a way to organize the collection because it serves as a reminder that we leave as we live: beautiful, absurd, brutal, merciful.

Can you describe your writing practice or process for this collection? Do you have a favorite revision strategy?

Thanks to my college, I went on sabbatical. I started by reading several hundred (thousand?) pages of last words uttered by famous/infamous/notable people, so my mind was on death the whole time. I wrote and revised in relative seclusion at my house. Working at nothing else full-time was far more emotionally bruising than I had anticipated. I had no buffer from the raw internal archaeology of writing: no teaching, no committees, no commute, no excuses. I’d write new works in wrenching outbursts. I’d look at old pieces and fight with lines for days, knowing that there was something in there I wanted to save. Sometimes I’d go to a coffee shop not to write but to be among living people rather than the restless revision ghosts.

How did you order the poems in the collection? Do you have a specific method for arranging your poems or is it sort of haphazard, like you lay the pages out on the floor and see what order you pick them back up in?

Organizing the book involved reams of paper, I’m afraid. I laid out the poems across the living room floor clustered around sticky notes of the last words I wanted to use, at which point my dog would spread out across the papers as if to remind me of how little any of it mattered. So I’d pet him and slide papers out from under him and talk to myself about what went where. He was my muse of ennui.

What do you love to find in a poem you read, or love to craft into a poem you’re writing?

I want words to take me past words. I want sighs and punched-in-the-gut grunts. I want to read (and write) lines that leave me staring past whatever I can see.

Can you share an excerpt from your book? And tell us why you chose this poem for us to read – did it galvanize the writing of the rest of the collection? Is it your book’s heart? Is it the first or last poem you wrote for the book?

The very last poem in the book, “Peopled,” calls on a lot of themes that pervade my writing: desire to escape, self-loathing, the futility of doing what I absolutely must do, even the odd trope of head injuries that I can’t really explain but can’t escape.

Peopled

I apologize

for the pollution of my footprint

and the ugly fossiled record

of having passed through.

Today I take to new country

that seems fertile from afar.

Come with me: we’ll unfound

a place intent on forgetting.

We will write on paper

then scatter pages

good and bad alike

to the south wind.

When the scraps fall back

like wordy unchilled snowballs

we will till them into the amnesiac earth

where each harvest

yields crops we never planted.

Surprise is a side effect of life concussed:

Were we really poets? Why?

If you had to convince someone walking by you in the park to read your book right then and there, what would you say?

Handing you this book is the most naked moment of my life. I want you to read not just my poems but the ‘me’ exposed in these pages, and I’m terrified that you will.

For you, what is it to be a poet? What scares you most about being a writer? Gives you the most pleasure?

I have trouble being vulnerable and asking for help. But in truth I am breakable, and I do need help to keep the pieces together. Poetry is my chance at connection. It’s my “buried life,” unearthed and shared. Because of that, poetry offers me both the most wonderful and most frightening possibilities. Being a poet is like walking around with bare wrists and handing razors to strangers. You hope they don’t cut, but you know you’re exposed.

Are there other types of writing (dictionaries, romance novels, comics, science textbooks, etc.) that help you to write poetry?

I find a lot of inspiration in nonfiction, mostly history and true crime, preferably a mix of both. Reading exploration narratives is also wonderfully poetic — I’ll read a medieval travel narrative in which someone tries to figure out how to describe something he (almost always a he, alas) has never seen. How do put a banana into words? It’s all metaphor and simile and imagery. Dictionaries are the absolute best. My first indulgent purchase when I landed a full-time, tenure-track job was the compact OED, complete with official magnifying glass. A dictionary is an endless, brilliant story of humanity.

What are you working on now?

When I started submitting the manuscript for How to Break My Neck, an editor commented that my poetry was quite good, “but very gendered.” That threw me into self-doubt — was my gender identity something I needed to “fix” or hide? But ultimately I’m a feminist; my identity as a woman can’t be neutered to create a poetic voice that ultimately coddles the ego of cis-gender men. All of this gave rise to my new manuscript, Banished, concerning a woman who is so unpleasant that she’s exiled from two consecutive towns. The basis is a Tibetan folktale about the toxicity of anger, but I decided to embrace the anger. And I set it in a rural Gothic poetic landscape to capture the sense of alienation and non-belonging.

What book are you reading that we should also be reading?

To get ready for my next semester of teaching, I’m re-reading one of my favorite novels, We Have Always Lived in the Castle by Shirley Jackson. It’s amazing. I have Bonnie Jo Campbell’s Mothers, Tell Your Daughters on my list next.

Without stopping to think, write a list of five poets whose work you would tattoo on your body, or at least write in permanent marker on your clothing, to take with you at all times.

Charlotte Mew, Stevie Smith, Philip Larkin, Tennyson, Shakespeare. That list is way too white, and Larkin was just an asshole. But I’m trying to play by the rules and not stop to think.

What’s a question you wish I asked? (And how would you answer it?)

Q. What are you most afraid of?

A. That I will always be who I am.

Purchase How to Break My Neck from ELJ Editions.

Jessica Walsh is a professor at Harper College, a two-year school outside of Chicago. I grew up in a small Michigan town on the Lake. I live with my husband Robert Frolick and our amazing daughter Stella, who is nearly 9 years old and would like me to write funny poems. I have two chapbooks out, Knocked Around and The Division of Standards. Find her online at www.jessicalwalsh.com.

Jessica Walsh is a professor at Harper College, a two-year school outside of Chicago. I grew up in a small Michigan town on the Lake. I live with my husband Robert Frolick and our amazing daughter Stella, who is nearly 9 years old and would like me to write funny poems. I have two chapbooks out, Knocked Around and The Division of Standards. Find her online at www.jessicalwalsh.com.

Published on February 22, 2016 06:04

No comments have been added yet.