Proper Planning Prevents… Something

I should have thought about the title a bit more before I started.

I should have thought about the title a bit more before I started.

A while back (last year in fact) Dan Morley asked me the following question about the nitty-gritty of planning my writing.

“How long do you plan (hours/days/weeks/months)? Do you sit and stare at a structure diagram for a couple of hours and then off you go? What I’m really asking is what a regular day’s planning looks like and whether it’s a case of repeating it the next day.”

At the time I was busy finishing my second contribution to The Beast Arises series so couldn’t answer in full, but I thought it was a great question which deserved proper consideration, and which may help others with their writing process.

*******************************

Most of my planning happens before I start the writing – it’s the initial part of the process rather than a day-to-day thing. At its heart, my daily planning usually boils down to ‘write another 3,000 words’.

If I was to break down the process into defined stages (and they usually don’t all occur in such a neat order) it would be Concept/ Brief – Themes – Scenes – Structure – Synopsis. Let’s have a look at each of those.

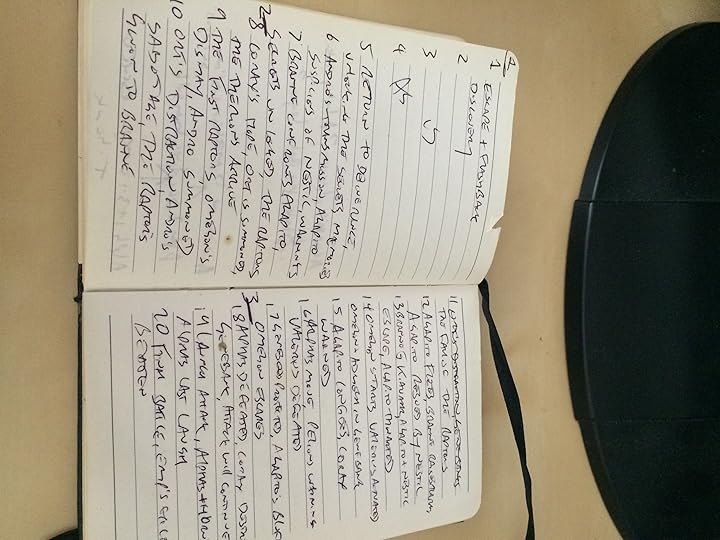

Early notes for The Bloody-Handed novella. Red ink=bloody! This story changed completely after a re-plan

This is the most basic element of the story, and it will either come from a random idea or a desire I have, or be given to me – either directly such as with some Black Library stories, or indirectly in the case of a themed anthology, for instance.

We’re not even at ‘elevator pitch’ stage yet. We’re at ‘It’s about Phoenix Lords’, ‘A story about beer’, ‘No dialogue’ and that’s it.

You may have lots of ideas for stories. Pick one and concentrate on it. Write down other ideas if you need to, but put them away. They aren’t important until you have finished this story.

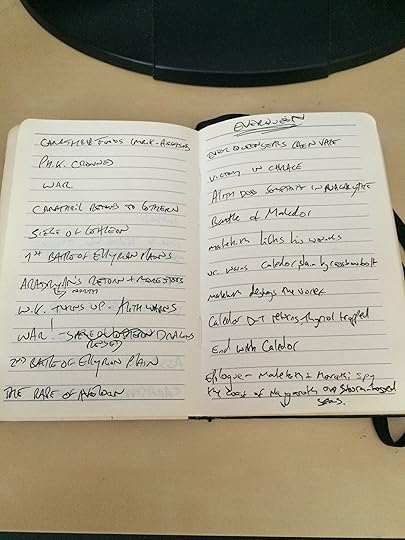

Plan for Caledor Plan for Caledor

Themes

Almost immediately after picking the concept/ receiving the brief, I’ll start noodling* about the themes that come with the idea. As an example, in my forthcoming Horus Heresy novel Angels of Caliban, I explore the nature of honour and loyalty. I looked at the cast of characters available and assigned thematic roles for them – what aspects of the themes would their actions embody?

Some thoughts for The Crown of the Conqueror

*Noodling is our catch-all term for any kind of thinking that requires time away from the keyboard, be it on a thorny issue of a current piece, or coming up with ideas for the future. To noodle is to do the brain part of writing rather than the finger part of writing. For this I might go for a walk, or do the ironing etc – any activity that doesn’t require too much brain power.

Themes may develop in later stages, but you need to have at least one, and more if the work is longer. As I’ve noted before, this is what the story is about rather than what happens. The themes should spring from the concept – in fact the initial idea may be a particular theme or question you want to examine.

Scenes

Certain plot points, lines of dialogue and specific vignettes or sequences start to come out of the theme. If your story is about betrayal, for example, there is going to have to be one at some point. As I write genre fiction this is also where some of the raw imagery comes from – things that are just cool in themselves, whether it’ll be a particular action sequence, a strange character or environment, and so-on.

I write down these disparate flashes of stuff. These are like a mood board for the story – set pieces and story beats that need to be or could be included. This is the most amorphous part of the process, which may be a couple of days if I have to come up with something on a tight deadline, or could be weeks, months or years in the percolation. As an example, some of the thoughts I’d had about craftworlds and Aspect Shrines that eventually appeared in my Path of the Eldar series had been bubbling away for a decade or so. There are still plenty I haven’t used yet.

More from The Crown of the Conqueror, putting ideas into a narrative sequence

More from The Crown of the Conqueror, putting ideas into a narrative sequence

This is not the stage to be critical. As Jim Swallow has said on panels, “Ideas are your currency, you need to spend them.” Not all of them will make the final cut, or end up in the exact same state in the final manuscript, but don’t pre-judge them.

This is notebook territory. Start a fresh page, write the name of the project at the top and jot down whatever comes to mind at any given time. Title ideas often come this way too.

This is also the most common type of day-to-day planning I do – I have an idea for the current project and I sit down and work out where in the plan I can fit it. It might be something that’s occurred to me while writing – like having to go back and insert some set up for a cool sub-plot that’s developed – or it might be something I want to include later. In the latter case, I make a note

[[[like this]]]

on the plan where I think the line of dialogue or scene should go.

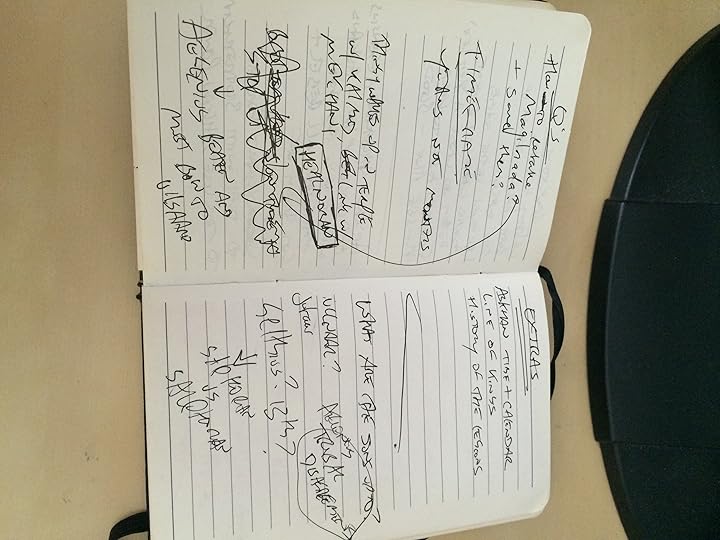

Questions and plot points for Deliverance Lost

StructureDepending on what sort of timeline I have there can be quite an overlap between the previous stage and this stage. This is where ideas are turned into stories; taking the different scenes, plots hooks, moments of awesomeness and deep despair, wrangling them into a coherent narrative.

At this juncture knowledge and experience of structure and pacing come into their own. I almost always start with a basic three-act approach. Intro-development-conclusion. The intro should be as brief as possible, getting into the meat of the story from the outset. This is also where the plot needs to get straightened out. If character A is going to have an awesome fight scene, how do we engineer that. It is also where the characters get fleshed out – notes on their motivations, backstory, etc.

Physically at this stage I often use a large flipchart and write on a sheet all the disparate nuggets of coolness and plot that I have. I annotate them with character notes and draw lines between them, connecting the dots of the character(s) journey.

Oh, did I mention I almost always start at the end? I have said this a few times, but you can’t plan well unless you know what you are aiming for. Start with the final scene, the big payoff and work backwards. For Z to have happened, Y needs to be in place. To move Y into place she needs to have overcome her fear of chickens in scene X… And so forth, lining up all of the ideas in turn so that when viewed from the start they move seamlessly from the start of the story to its inevitable conclusion.

More Deliverance Lost planning

More Deliverance Lost planning

There are of course gaps. This is where ‘targeted noodling’ needs to come into play. The plan then becomes one of coming up with solutions to particular plot points or character development issues. For example, do you need another scene that shows the character’s short temper, setting up their pivotal outburst later in the story? How exactly does the princess steal the sword from the dwarfs? The goal here is not to come up with an answer – that’s pretty straightforward – but to come up with the most entertaining and appropriate answers.

Some writers, particular screenwriters, like to use a ‘beat sheet’, which is sort of a written storyboard. You can find a nice introduction to the concept here by Larry Brooks. Some programs like Scrivener are set up to allow you to create a kind of interactive beat sheet, allowing you to mix and match scenes and move stuff around like file cards before collating them into a single document. I want to try Scrivener again when I have a bit more time, I think it will prove really useful if I can get my practises moved over to its interface. (Also, don’t you hate it when you reach the bottom of a page on Word and have to scroll down because you need to see the space into which you are typing? Scrivener doesn’t do that, it keeps the active line in the middle of the screen. Small but very useful things like that can make a difference to focus and writing speed.)

It is a lack of extra noodling at this stage that most often catches me out during the writing itself. I am faced with reaching a point at the start of a chapter, for instance, and not knowing already exactly what is going to happen or how the scene looks and feels. This really slows me down, forcing me out of typing mode and into noodling mode.

Noodle-thoughts for Deliverance Lost

SynopsisThe last part of planning (though not always definitive) is the synopsis. This is where you take the pages of notes, squiggly lines, margin comments and doodles and turn them into a coherent set of words. The format here can vary from bullet points to lengthy description and chapter-by-chapter breakdown. Or a mix depending on how much info you need at any given point in the book – more detail on the set up and ending, less in the middle sometimes (though this is often where novels in particular can lose their momentum, having laid down the foundations but not ready to start the build up to the climax – make every scene push forward to the conclusion). Whatever works for you to have a narrative template to work from.

I used to have quite specific chapter breakdowns in my synopses, because it helped me gauge the length. For instance, if I assumed an average of 2,000 words per chapter (not uncommon) I would need enough story for 45-50 chapters to write a 100,000 word novel. Or perhaps I wanted each chapter to be longer, encompassing several scenes, changes of perspective and so on, so I would break the story down into 25 chapter to allow 4,000 words per chapter.

I don’t do that so much now, because I’ve run into situations where I’ve included something on a chapter plan that, in the course of writing, is clearly only going to be a few hundred words; conversely some single chapters, particularly big battles, might end up sprawling over more chapters than intended. These days I will often just write the whole thing in scenes and sections and then insert the chapter breaks at suitable, natural cut-off points in the writing.

Early plotting notes for The Lion

The important thing to remember is that any plan, even a synopsis approved by an editor, is subject to change if a better idea comes along. Having the plan, having the structure in place to allow you to analyse and manipulate the story detached from the actual words and sentences, allow you to look at when you hit high and low points with more clarity. It is like an x-ray of the skeleton from which the flesh of the narrative is hanging, revealing any fractures and painful contortions beneath that need to be fixed. Without this kind of plan, it can sometimes be hard to work out why a story seems to flag in the middle, or the ending seems drawn out or rushed, or many other problems that beset stories and novels form time to time. Seeing the scenes, the story beats, unadorned with beautiful prose leaves them bare to your scrutiny.

If you’ve found this interesting, take a look at my other blogs on planning. If you have a completely different way of approaching your planning process, I’d love to hear about it in the comments (along with any other questions you have about the writing process).

**To make sure you don’t miss out on any blog posts, you can keep up-to-date with everything Gav by signing up to my monthly newsletter. As a bonus, every other month I randomly pick a newsletter subscriber to receive a free signed copy of one of my books.**