Interview With R.M. Huffman

I very much enjoyed R.M. Huffman’s novel Leviathan: Book One of the Antediluvian Legacy, and it was an honor to have the opportunity to ask Dr. Huffman some questions about his life, his work, and his faith, all of which figure prominently in his writing.

You’re a practicing physician, writer, illustrator, husband, and father of four small children. How do you find time to create?

I started writing the book that became Leviathan when I was an intern. Every few days I’d be post-call, which means I’d have most of the day off after spending the night at the hospital, and – this is the key part – I can’t take naps. I’ve just never been able to do it. Writing turned out to be a relaxing sort of thing I could do while resting on the couch, sometimes with a baby sleeping on me, and at some point during my residency I had done enough of it that I had an entire manuscript. These days, the writing is a bit lower on the priority list and gets done a couple hundred words at a time, early in the morning or late at night or if I have a long break between cases. It’s slow going, but it goes, and I’ve written 75K+ words in the sequel (and about 10K in book 3). The cliched-but-true moral of this story: if I can do this, anybody can.

You’ve mentioned C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien as influences on your world-building. Who are some of your other favorite fantasy authors?

You’ve mentioned C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien as influences on your world-building. Who are some of your other favorite fantasy authors?

My favorite current (urban) fantasy series is The Dresden Files, by Jim Butcher. His world-building is top-notch, and he’s kept it consistently entertaining for fourteen or fifteen books now. Robert E. Howard’s Conan stories probably have the most “pre-flood world” flavor of any well-known fantasy setting, but my favorite character of his is Solomon Kane, whose somber, no-nonsense Puritanical attitude and wandering monster-killing ways probably seeped into Noah’s characterization, especially in book 2.

If there’s anything philosophical or theological you’d like readers to take away from Leviathan, what would it be?

That the plain text of Genesis 2 through 6 is completely fascinating and deserving of more interest and study than it gets now, which is virtually nil. Also, half-angel giants riding dinosaurs is almost certainly a thing that really happened.

How far do you plan to take The Antediluvian Legacy series? To the building of the Ark? The Flood and beyond?

The series is planned to be a trilogy, and book 3 will include the building of the ark, the flood, and the immediate aftermath. The last third or so of the book will be the “Noah’s ark” narrative that’s familiar to most people, but hopefully with an emotional and historical context that will make it more harrowing and compelling than the typical smiling, white-bearded-man-with-happy-giraffes Sunday School version of the story.

You’ve made many of the Naphil characters in Leviathan decent, moral people, but the Lord sends the Flood, in part, to clear the world of Nephilim. How can the modern reader square God’s erasing of the Nephilim from the Earth with the idea that the Nephilim are not responsible for their parentage? Doesn’t that seem unjust?

The Nephilim are described as “heroes of old, men of renown,” so I felt like it was reasonable, at least initially, to depict them as such. Now, because of the worldwide judgment of the flood, we know that they eventually become irredeemably evil, but so did everyone else. I get into this in the books, but I do think that there were probably a great many pre-flood folks, Nephilim included, who clung faithfully to a God-fearing morality and were killed for it, much like Christians under Nero or Jews in the Holocaust or [pick another of many awful examples throughout history]. Anyway, I don’t believe that the Nephilim were necessarily condemned by their parentage (at least, the text of Genesis doesn’t state such a thing). It does seem that a driving motivation for Joshua-era Israel’s mandate to destroy the inhabitants of the promised land could have been that many of them were of the “…and also afterwards” Nephilim ilk (Rephaim, Emim, Zamzummin, Anakim – see Deuteronomy chapter 2), but

even then, cultural depravity was likely the main (or only) factor. However it ultimately went down, I know that 1) God is perfectly just, 2) Genesis 6 gives very little specific information about either the Nephilim or the global depravity that demanded that a just God destroy the earth, which means that 3) despite any semblance of unfairness, if we had complete information about the societal milieu and individual behaviors of the antediluvian world immediately preceding the flood, we would have no doubt that destroying the world was a just God’s only option. In fact, that’s going to be the challenge in the third book: how does one depict a world that becomes so bad that the reader feels a sense of massive relief and cathartic satisfaction when the flood judgment finally does come? Hint: it’ll be a bit worse than “Noah’s neighbors make fun of him while he’s building the ark.”

Many people consider Creationism to be anti-science. How do you reconcile being a practicing anesthesiologist and a Creationist?

This deserves a 10,000 word answer that encompasses epistemology, the original text of Genesis, the nature of “macro-” versus “micro-” evolution, and the history of scientific philosophy beginning with James Hutton and uniformitarianism, but I’ll just hit the high points. An “evolutionary biologist” is a scientist in the sense that someone fluent in Orcish or Klingon is a philologist, and the works of Richard Dawkins are comparable to Rudyard Kipling’s Just So Stories. It’s worth noting the difference between empirical science (experimental, measurable, repeatable, responsible for antibiotics and airplanes) and historical science (data is interpreted within an axiomatic paradigm). Whether one is a creationist or a Darwinist depends not on evidence, but interpretation of the evidence, which becomes a philosophical matter, not a scientific one. As a Christian, my axiom is “the Bible is authoritative in every respect,” and its explanatory power as relates to everything from natural history to human behavior is immensely satisfactory. As far as Biblical creation being an idea that’s “anti-science,” the following people would disagree: Newton, Kepler, Mendel, Pasteur, Pascal, Cuvier, Faraday, Kelvin, Boyle, Linnaeus, and Francis Bacon, who came up with the concept of the modern scientific method in the first place. Anesthesiology is a pragmatic medical specialty (for example, do you know how modern volatile anesthetic gas works? Neither does anybody else, but it does! Hooray for the Manhattan project, where its chemistry was developed!) and not particularly beholden to belief about origins, but as a physician, I’ll say this: the idea that the self-replicating, self-healing, autoregulating, sentient machine that is the human body is a product of chance mutations of a spontaneously-arising functional DNA/protein interface is scientific nonsense. Mutations cause trisomies and cancer, and the number of known mutations that have been found to be both beneficial to survival and additive to a genome is exactly zero. A Creator with intelligence beyond our capacity to comprehend is the only reasonable conclusion; in fact, Francis Crick, co-discoverer of DNA, strongly rejected belief in God but had such a problem with the materialistic origin of life that he ended up espousing panspermia, the idea that life on earth was seeded by aliens.

So, that was only like a 5,000 word answer. Even shorter: it isn’t hard, and those people are silly.

What were the hardest parts of the novel to write? The easiest?

Hardest: romantic stuff. Easiest: violent encounters between prehistoric beasts and people with cool weapons.

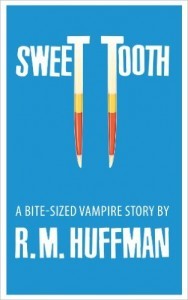

Tell us about your Sweet Tooth series. Are you more comfortable writing that sort of lighthearted humor than the serious material in Leviathan?

Sweet Tooth originated from the (hilarious!) idea that the glucose-laden blood of an uncontrolled diabetic would be like candy to a vampire. I wrote the story, I was highly entertained by doing so, and I did five more with the same character. They’re sort of urban fantasy/horror with, yes, lighthearted humor, each one with a different holiday theme. I did find them easier to write, actually. With these, I didn’t have to worry about anachronisms or avoiding modern idioms or creating a fantasy setting, and with a protagonist who’s a sarcastic vampire doctor and myself being two out of three of those, I pretty much just used my own voice. I’m biased, of course, but I have to say, I think most people would like them and find them to be subversively clever.

When Noah speaks, do you imagine him having the voice of John Huston in The Bible: In the Beginning… or Russell Crowe in Noah?

Great question. I’m honestly not sure, but I figure I’ll find out when Mel Gibson, bringing his Braveheart/Passion of the Christ/Apocalypto directorial sensibilities and playing the part of Methuselah, casts the Antediluvian Legacy movies (filmed back-to-back-to-back, of course).