Hello Sweetheart…Get Me Val Sears

Hello, sweetheart. Yeah, get me rewrite will you? One of the giants has fallen, Val Sears, a newspaper legend out of a time of newspaper legends.

Whaddya mean you don’t know who Val Sears is. Val wrote features and covered politics in Ottawa, Washington, and London for the old Toronto Telegram and later for the Toronto Star. He wrote the great Canadian memoir about the Toronto newspaper wars of the 1950s, Hello Sweetheart…Get Me Rewrite.

Val was class, let me tell you; elegance and grace personified, both in print and in life. He was sort of the Scaramouche of newspapermen, blessed with the gift of laughter and a sense that the world was mad.

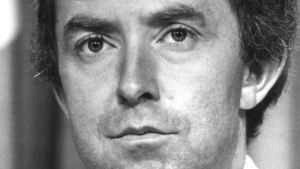

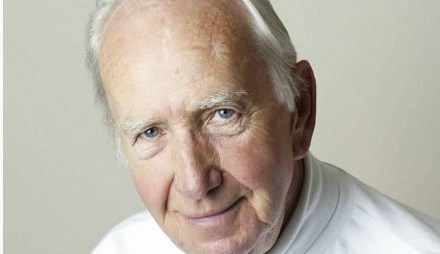

Yeah, hold on a minute, will you, sweetheart, while I brush away a tear. This is one of the tough ones. I loved the guy. When I grow up, I want to be a newspaperman like Val Sears. He was tall, laconic, with snowy hair pushed back from a smooth face, mouth turned at an angle as if he knew instinctively that whatever words came out of it were going to be laced with acid, and he was already savoring them.

Val moved slowly when he came into a newsroom or a bar or a cocktail party, taking in the world at his leisure. If he didn’t already know everyone in the joint, he soon would. Val was on the press plane when U.S. presidential candidate Ronald Reagan insisted a female reporter run her fingers through his hair to demonstrate that he didn’t dye it. Val still didn’t believe him, of course. Val never believed much of anything that a politician ever said.

The first time I met him, it was at a press reception then-Opposition leader Joe Clark threw in the garden of his Stornoway residence. I was in Ottawa doing a magazine piece on a controversial Progressive Conservative member of Parliament named Tom Cossitt. Cossitt is forgotten now, but at the time he had caused the Conservatives considerable embarrassment with his outbursts against bilingualism.

I wanted to talk to Clark about Cossitt. However, the people around their leader didn’t want anything to do with the story. They told me I could come to the reception but to stay away from Clark.

I was standing there wondering what to do when Val entered, lazily taking in his surroundings and then sauntering over. We introduced ourselves; he wondered what I was doing in town. I told him I was writing about Cossitt, but they wouldn’t let me talk to his boss.

“Joe?” Val said with that crooked, sardonic grin of his. “Hold on a minute.” He immediately went over to Clark spoke to him, nodded in my direction, and the next thing I knew I was talking to the Conservative leader, getting the quotes I needed for the story.

After that, Val and I became friends—or I liked to think of him as a friend. I was dazzled by him, his intelligence, his humor, the way he carried himself, the way nothing seemed to faze him, certainly not politicians, newspaper editors or women.

Okay, hold on, sweetheart. Maybe women could shake him up a bit. After all, he was human.

I always looked forward to our encounters, listening to that easy patrician drawl as it declaimed about the politics of the day in Ottawa, Washington, and in that particularly scabrous hotbed of gossip and rumor, the Star newsroom.

The homages to Val all pointed to the time in 1962 when Prime Minister John Diefenbaker called an election, and Val strolled into the press gallery—he never would have hurried—and announced, “To work, gentlemen, we have a government to bring down.”

But my favorite Val aphorism was “I’ve been around since the earth cooled.” Well, you got that right, sweetheart, I’ve now been around long enough to use the phrase myself, and I always think of Val when I do.

Yeah, I guess I am a little choked up. When I heard about Val’s death at the age of eighty-eight, I sat alone for a few minutes and let the tears flow. Yes, of course for Val, sweetheart, but also for the era that’s gone with him.

It’s probably mostly in my imagination at this point, but in those days newspapermen—a few women back then, but mostly men—were colorful, larger-than-life characters, livelier than most of the people they covered, world-weary, cynical, not taking guff from anyone. I was a kid then, freshly escaped from small town Ontario, newly arrived in this enthralling newspaper world, totally in awe of these guys.

Val, well, he loomed larger than any of his contemporaries. He was certainly more colorful, a little more world-weary and a lot more cynical and funny, with an added dash of sophistication thrown in for good measure. In his heyday, Cary Grant could have played Val. Or maybe it was Val who was playing a variation on Cary Grant. Hard to tell.

So that’s it, sweetheart, let’s dry the tears and put 30 on this. Whaddya mean you don’t know what “30” means? That’s the newspaper term for the end of the story. When you saw 30 back in the day, you knew it was over. Finished.

So you put “30” on Val’s life, will you? Hate to do it. Hate to think he’s not around anymore.

If I still drank, I’d lift a glass to Val Sears and the lost newspaper era in which he flowered. As it is, I think I’ll just sit here for a while and remember the guy who’d been around since the earth cooled. That earth is a little duller today.

Yeah, thanks, sweetheart. Tell you what? Why don’t we get together later at the press club for a drink? Listen, if my mother calls, don’t tell her I’m a newspaperman, okay?

She still thinks I’m a piano player in a whorehouse.

30

![old-typewriter[1]](https://i.gr-assets.com/images/S/compressed.photo.goodreads.com/hostedimages/1453808427i/17873947._SX540_.jpg)