The RMB’s Future: Four Views

At the last ASSA meetings in San Francisco, I participated in a Society for the Study of Emerging Markets panel entitled “Can the Chinese Renminbi Rule?: If So, How and When?”

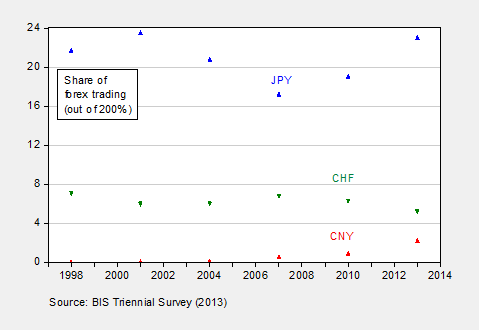

Figure 1: Share of currency in foreign exchange trading (out of 200%), in April. Source: BIS triennial survey.

Here’s the program.

Panel Moderator: ALI KUTAN (Southern Illinois University Edwardsville)

MENZIE D. CHINN (University of Wisconsin–Madison)

ESWAR S. PRASAD (Cornell University)

ROBERT MCCAULEY (Bank for International Settlements)

WING THYE WOO (University of California–Davis)

I began the discussion with a review of what is necessary for a currency to become an international currency, based upon my assessment of BRIC currencies as reserve currencies, and my analysis with Hiro Ito of invoicing currencies. In both cases I stressed the role of network effects and hence inertia, combined with the importance of financial development. I did argue that more East Asian currencies are anchoring to the CNY over time.

In his presentation, Eswar Prasad highlighted the progress that has been made in RMB usage in international markets, use as a reserve currency, but the doubts that the RMB could become a safe-haven currency, like the dollar. Some of these points are made in his June 2015 FT piece:

The renminbi is on a seemingly inexorable march towards becoming a global currency. It is already widely used in international trade and finance transactions. Now China wants the International Monetary Fund to label the renminbi an official reserve currency by including it in the exclusive group that make up its unit of account, the Special Drawing Rights. That group comprises the dollar, the euro, the yen and sterling.

There are good reasons to welcome the renminbi’s rise. Its trajectory is closely correlated with banking and other reforms that will make China’s economy more market friendly. These are necessary to establish a more balanced and less-risky growth path, one that is less dependent on investment, generates more employment and reduces environmental degradation.

Bob McCauley argues that country-specific attributes are not the key to determining whether a currency becomes an international one; rather global factors are. His presentation is here.

Finally, Wing Thye Woo argues that time is of the essence. In his presentation [slides to come], he repeats these points:

n the first scenario, China becomes caught in a middle-income trap, with per capita GDP stuck at 30% of America’s – an outcome that has characterized Latin America’s five largest economies since at least 1960, and Malaysia since 1994. This would put China’s economic strength relative to the US at 1.1 – well below the necessary ratio.

In the second, more favorable scenario, China’s per capita GDP would reach 80% of America’s – higher than the 70% average rate for the five largest Western European countries since 1960 – and its economic strength relative to the US would amount to roughly 2.8. This would make the renminbi eligible for IVC status and enable Shanghai to choose whether to become a 1-IFC. But China’s economy still would not be strong enough relative to the US for natural market forces to ensure the renminbi’s international success.

Given this, the Chinese government would have to implement decisive measures to encourage international traders and creditors to price their transactions in renminbi. Specifically, China would have to use its market power to promote pricing in renminbi for relevant manufactured exports and raw-material imports, and encourage renminbi denomination of foreign financial assets that China purchases (which the country’s status as a net creditor should facilitate).

Menzie David Chinn's Blog