Questionable: Patterned Structure

Briana wrote:

I am fascinated by and want more about patterned structures in story-telling. I don’t have a specific question, though . . . .

To understand patterned structure, you have to forget cause-and-effect, chronological order, and time as indicators of story movement. Patterned structure is an entirely different animal, in many ways female to the overtly male linear structure.

So you have a story in mind, but it’s not about how something happened. It’s about how things layer with each other or bump up against each other, and in so doing take on new meanings because of that juxtaposition. It’s structure built on relationships instead of cause and effect.

So here’s a scene:

It’s about Mary who’s arguing with Harold about the danger of acid rain.

Here’s another scene.

This one’s about Harold telling Marvin that his meteorological research is crap.

Here’s another scene.

This one is Harold and Mary trapped inside an isolated cabin by a bad snowstorm.

These scenes are all separate. Harold’s argument with Mary does not lead to him yelling at Marvin or getting trapped by a snowstorm with Mary. It doesn’t matter when these scenes happened because there’s no cause and effect. But if you look at them closely, you begin to see relationships. The more scenes you have, the more the relationships emerge:

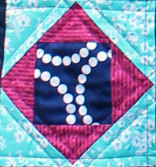

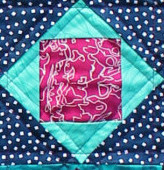

Just as you see repeated colors, textures, and patterns in the quilt blocks, you see repeated characters (Harold and Mary), repeated subjects (the weather), repeated actions (people at war with each other) in the story. The more blocks/scenes you see, the more relationships emerge: Marvin is Mary’s brother, Mary is Harold’s lover, Harold is Marvin’s boss. When all the pieces are in place, all the scenes are written, the pieces combine into a whole that illuminates what the story is all about. Like this:

The individual pieces aren’t important; it’s the way they combine in the viewer/reader’s perception to make a whole that matters.

Two excellent literary examples are Mary McCarthy’s The Company She Keeps (1942) and Margaret Atwood’s “Rape Fantasies”. Spoilers below.

McCarthy’s novel at first seems to be a collection of six short stories about different men in the 1930’s, but as you read through the pieces you see the pattern: they’re all about the same woman, Margaret, who changes with the different men she’s with, attempting to define herself each time, trying to fit into a world that defines her by the men she’s been with, what her current husband calls her “bad record: a divorce, three broken engagements, a whole series of love affairs abandoned in media res.” (The subtext is clear that the abandonments were media res because the men weren’t ready to abandon them, but Margaret was.) It’s not until the sixth story, this time with Margaret’s psychoanalyst, that the pieces come together. Margaret’s last words are “Preserve me in disunity,” a promise that she won’t fit in, that she’ll be all of the women she’s been and will be, a multiplicity. There’s no other way to tell Margaret’s story effectively except to tell it in pieces because Margaret is in pieces and is determined to stay that way, refusing to be assembled into a pleasing, linear line that men will understand.

Atwood’s “Rape Fantasies” is a pattern of funny scenes that form a poignant whole. It begins with the narrator, Estelle, telling somebody about talking about rape fantasies with three women at work on their lunch hour two days previously. Estelle explains that the other three told rape fantasies that are really sex fantasies and not rape at all, as she points out: “Rape is when they have a knife and you don’t want to.” Then she tells one of her rape fantasies: she’s walking along the street and this guy grabs her arm, and she says, “You’re trying to rape me, aren’t you?” and he nods, so she piles all the stuff in her purse into his hands (he’s polite) until she finds the plastic lemon juice lemon she keeps there, but she can’t get the lid off, so he helps her, and then she squirts him in the eye.

Estelle feels that was kind of mean since he was being so helpful, so she drops the “I was at work” part of her story and goes on telling whoever’s listening about other rape fantasies she has, and they’re all different, pathetic guys, crazy guys, dying guys, but you begin to see the similarities: in every one of her fantasies she escapes by talking her way out, telling them about herself, recommending her dermatologist, establishing relationships. And just when you think this woman is funny but nuts, Atwood hits you with the end that pulls all the different pieces into the patterned whole. Estelle tells her listener that she’s always careful when she goes out for a drink:

“Like here, for instance, the waiters all know me, and if anybody bothers me . . . I don’t know why I’m telling you all this, except that I think it helps you to get to know a person.”

The last thing Estelle says in her story is:

“Like how could a fellow do that to a person he’s just had a long conversation with, once you let them know you’re human, you have a life, too. I don’t see how they could go ahead with it, right? I mean, I know it happens, but I just don’t understand it, that’s the part I really don’t understand.”

And there’s Estelle in brilliant detail, all her fantasies given in conversation with a man she’s talking to in the hope that he’ll ease her lonely life and not rape her because she’s talked to him. You can’t tell Estelle’s story in linear structure because her fantasies aren’t linear, one doesn’t cause the next one, they’re pieces in the puzzle that is lonely, fearful, funny Estelle.

Modern movies have done some great things with patterned structure, Pulp Fiction being the real trail blazer there, but my favorite patterned film is Out of Sight, the story of Jack, an escaped convict who falls for Karen, a federal marshall. Except it’s so much more, so the only way to destroy the deadening effect a linear structure would have on the story is to break the linearity and tell it out of chronological order, juxtaposing scenes so their meaning is in their relationships and not in cause and effect. This approach also led to one of the greatest love scenes ever filmed. Jennifer Lopez’s Karen has traveled from Florida to Detroit to bring in George Clooney’s Jack even though she’s half in love with him and he’s besotted by her. She’s having a drink in her hotel, having fended off some terrible passes from guys in suits at the bar, when Jack sits down across from her and they begin to pretend they’re not cop and criminal, they’re Celeste and Gary, normal people meeting in a bar.

Steven Soderbergh, the movie’s director, could have done what follows in two scenes, the two of them talking in the bar followed by the two of them making love in her hotel room. Instead he fragments both scenes and puts them together in a pattern, illuminating both scenes in a way that chronological linearity could never have accomplished:

Now try to imagine that as two chronological scenes. All of that intensity and emotion would have been lost. In fact, watch Out of Sight in its entirety–it’s a terrific movie–and then go back and imagine the same scenes told in chronological order and you’ll see that the story loses all of its impact and becomes just another cop movie. Because the story is about everything both of these people are colliding at this one time, patterned structure is the most effective way to go.

However, there’s a drawback: Patterned structure is difficult as hell to do well and really only works when the story itself demands it because unless the story depends on the fragmentation, the collection of out-of-sync scenes will just confuse readers and viewers who are trained to understand narrative in chronological order. You have to be a master storyteller to make patterned structure work, one of the many reasons I’ll never do it.

[Quilt is by Cath Hall of Wombat Quilts.]

The post Questionable: Patterned Structure appeared first on Argh Ink.