Now What? Why Revising Your Novel Can Mean Filling It With Stuff You Like

You wrote a novel! Now what? NaNoWriMo’s “Now What?” Months are here—this January and February, we’ll be helping you guide your novel through the revision and publishing process. Today, Michelle Hodkin, author of The Mara Dyer Trilogy, shares her revision structure… and why revision involves thinking about the treasures you’re storing away for your future reader:

Dear Novelist,

I say ‘novelist’ because you are, in fact, a novelist now. You put one word after the other, created page after page, and you wrote 50,000 words in one month. It’s incredible, what you’ve done—I have three books under my belt, but I’ve never achieved what you have. Because here’s my dirty little secret: the act of drafting, of putting words on a page where none existed before? It’s my least favorite thing about writing.

Which, given that that is writing, probably makes you wonder what I’m doing writing books anyway and where I get off Telling You How to Do it. That is a valid question. Here’s my honest answer: my first novel just poured out of me. I didn’t think before I sat down to do it—my big idea was literally, “Something happens to someone.” But for whatever reason, some strange alchemical compound of compulsion mixed with ignorance and confidence, I ended up with 80,000 words in four months.

That was the first, and only, time that a book ever happened to me. Now, I have to happen to my books. And when I’m faced with a blinking cursor and blank space, I panic. There are so many words in the world, so many ideas, so many characters and plots and subplots to choose from, I freeze. Every day I’m confronted with infinite possibilities for what could happen, and having to choose is paralyzing.

But somehow, I pass that point. I’m astounded when it happens, and I’m not sure I completely understand how it happens. But it does. And the result is a document full of words and ideas and feelings—a mess of them. The document resembles word soup more strongly than it resembles a book.

But that’s when my favorite part of writing kicks in: revision.

One thing I’m not going to do here is Tell You How to Revise. Because writing happens differently for everybody—some writers need a windowless room and a typewriter and nine interrupted hours a day to do it. Other people need wine. The point is, like writing, the revision process is going to be different for you than it is for me, because we are different people, and our first drafts are different beasts. So what I’m going to tell you is How I Do It. YMMV.

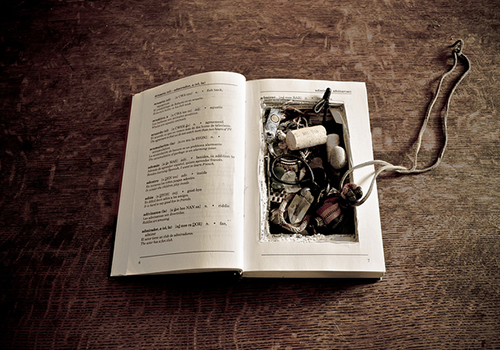

When I face off against the first blank page of a new novel, I create two documents—one is called Sh*t I Like, the other is called Sh*t I Want. Since I don’t want to keep repeating the word sh*t, let’s just call them bins. In the Like Bin, I’d put in everything I wanted my embryonic book to feel like, or in some cases, just things I was thinking about when I wrote it. Examples include: Jurassic Park (I’m always thinking about Jurassic Park). SAW. The Little Prince. Invitation to a Beheading by Vladimir Nabokov. Magneto and Professor X. Hey Dude. Lorde. Pretty Monsters by Kelly Link. Ronin. Horns by Joe Hill. The Ring. Adventure Time (the Jake vs. Me-Mow episode specifically). When I write, I’m like a magpie—I read books and watch movies and eavesdrop on conversations on the subway and when I hear or see or feel something new or interesting or shiny, I snatch it.

In the Want Bin, I’d put in stuff I knew I wanted to write into the book. I wanted a subway tunnel. I wanted the No Name Pub on No Name Key, FL (real place, BTW). I wanted a vivisection, didn’t care whose, didn’t care why. I wanted an accountant named Ira Ginsberg. I wanted some hitchhiking and some auto-theft. I wanted a mannequin factory. I wanted to put in a sex scene I wrote in November 2012 and had been dying to use ever since.

And when my draft was finished, I would feel relief so powerful that I would actually shed tears. And then I’d get to work, the work I love, the work of fixing it.

Make no mistake: it’s hard work. Novelist Sara Zarr said, “Revision is where you earn your money, and if you haven’t earned any money yet, revision is where you pay your dues.” And because the way I write is so chaotic, my revision process tends to be pretty structured.

The first thing I do when I begin my revisions is create another document. Before even reading over the draft, I make a list of all of the things that I know I’ll need to fix. I label this document BIG PROBLEMS. As I read through the draft, I’ll create another list, and call it “small problems.” Easy enough, right?

Then I read through the draft and I add to the lists. But while I’m adding Problems, I’m also looking at the two bin documents where I put all the thoughts, feelings, ideas, and general crap that I originally hoped the book would feel like, and all of the things I wanted to write into the book. I think about my draft, and I think about my readers. This is important to me—I think about whether the things I’ve written are going to produce the feelings I want my readers to experience. Which leads me to the next step.

As a novelist, before anything else, I want my books to be fun and entertaining. But you can’t please everybody, so what I did, and do, is think about who my audience is. Who my Dream Reader is. In my case, that is fifteen-year-old me. Then I check the bins to see if any bits in there would make her bored enough to abandon the book to play Donkey Kong Country instead, or would make Teen Me roll her eyes when I was hoping she would genuinely laugh. If I can recognize those bits myself, I add them to my “Problems To Be Dealt With At Some Future Date, Not Today,” list. But inevitably, there are bits in those bins that I might love, but aren’t serving my story, and I’m too close to my draft to recognize that. And that’s where my Readers come in.

Readers, beta readers, critique partners—it doesn’t matter what you call them. These are people who are going to examine your minimally clothed, badly dressed, possibly malodorous draft and tell you what they like and what they hate about it. They are people you need to trust. If that trust isn’t there, you might honestly be better off going it alone—I’ve had a bad critique partner experience, and it was nothing less than scarring. I don’t know any writers who go it alone by choice, and I’m lucky to have moved past my crappy experience to have found some truly incredible people who have taught me incredible things.

There’s my First Reader, who sees my draft before I’ve even attempted to fix any of its Problems, which is like taking off your clothes and saying, “Now, please inspect my body with a magnifying glass and point out each and every flaw.”

I trust her to tell me the hard truths in a way that won’t break my spirit to hear them. After I get her notes, I add them to my lists of Problems, and then, finally, I start to address them. I fix as many as I can in the best way I know how. But there are always going to be times when the best way I know how is not good enough.

So I send the book to my Second Readers, a small group of two or three people who are extra excellent at the novel-writing skills I’m least confident in. In my case, those are structure and plot. I also give these readers my lists and my bins and ask them, if I’m struggling with something specific, if they can help me think of how to write my way out of it. Sometimes that way involves changing which characters are in a scene. Sometimes that way involves cutting a scene entirely. And sometimes, after I read their notes, I’ll realize that to turn the draft into the book I want it to be, I need to rewrite the whole thing.

It could happen to you. I’m not saying this to scare you, I’m saying this because it’s happened to me one, two…four times, maybe, if not more. I’ve scrapped all but a few thousand words and started over completely, blowing deadlines and disappointing readers. It was painful, but my book rose out of the ashes sleeker and sharper and just better in every way than it was before. And ultimately, what people remember is how good your book is—not the date it came out.

But that is an In Case of Emergency Break Glass move, and you shouldn’t attempt it before you spend some time away from your book. Don’t break up with it—just, you know, go on a break. Read some other books. Spend time with your kids/pets/friends so you can recognize them in a crowd again. Then, after two weeks, or two months, or as long as you can afford to stay away—take your book back.

When I read mine for the last time, I look at those documents I started with, the lists and the bins, and I see what made the cut, what didn’t, and whether the book is better for each of the changes I made. Some novelists at this stage are able to decide for themselves whether the pages they hold are from the book they meant to write. I’m not one of them. I’ve finished three books, but I still don’t have that kind of confidence. I second guess myself all the way through.

Which is why I also have a Last Reader. When I send my final, final draft to her, it’s like stripping naked again—I’m even more nervous and vulnerable than I was in the beginning, because I’ve invested so much time and effort trying to make my book beautiful. When she tells me it is, I truly believe her, and I can finally let it go.

You will make your book beautiful, too. And if you can’t quite believe that yet, your first step is to find someone who will.

See you on the other side,

Michelle

Michelle Hodkin is the author of the New York Times bestselling Mara Dyer Trilogy, which includes The Unbecoming of Mara Dyer , The Evolution of Mara Dyer , and The Retribution of Mara Dyer , one of TIME.com’s Top 10 YA Books of 2014. Michelle grew up in Florida, went to college in New York, and studied law in Michigan before finally settling in Brooklyn. When she isn’t writing, she can usually be found prying strange objects from the mouths of her two rescued pets. You can visit her online at michellehodkin.com.

Top photo by Flickr user Mike Shaheen.

Chris Baty's Blog

- Chris Baty's profile

- 63 followers