Pierre Boulez and the sound universe

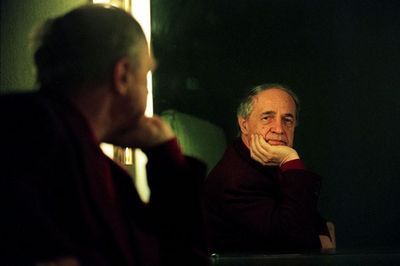

Photo Mike Powell/Times Newspapers Ltd

News of the death of Pierre Boulez ��� the composer, conductor, innovator and then icon ��� comes several months after the conclusion of celebrations marking his ninetieth birthday. Boulez���s was a long life of notable achievements: the seminal serialism of Le marteau sans ma��tre (1955); an international conducting career; many notable recordings of a wide orchestral repertoire; instigating the Cit�� de la Musique in Paris's Parc de la Villette; the live electronics of R��pons (1981) that emerged from his research centre in Paris, the Institut de Recherche et Coordination Acoustique/Musique (IRCAM), opened in 1977. That was also the year in which Boulez���s wise words about technology and music appeared in the TLS. . . .

Boulez is far from being the only musician who���s written for the paper. For one thing, there���s a band of notable composers who have shown in the TLS they can write critical prose, as well as musical notes for performance, with Hugh Wood, Judith Weir and Thomas Ad��s among them. (And in the early years, Elgar contributed a few erudite letters on literary notes, including Tennyson's use of the word "poluphloisboisterous".) Yet "Technology and the composer", published on May 6, 1977, may be of especial interest, being all but a personal manifesto in impersonal guise. It mentions no composer or piece of music by name, but bears a clear relation to Boulez's work at the time; it also, characteristically, asks keen questions concerning music's future.

���Technology and the composer��� was the first English translation (the translator remains anonymous) of a piece that had only appeared earlier that year in French, in IRCAM's Passage du XXe si��cle. "Invention, in music", it begins, "is often subject to prohibitions and taboos which it would be dangerous to transgress." (Perhaps he was thinking back to the time when he and the ethno-musicologist Andr�� Schaeffner smuggled "gongs and tam-tams through the cellars of the Palais de Chaillot, no doubt to avoid the time, paper and expense involved in any French bureaucratic exercise".) Western culture in the twentieth century, as Boulez saw it, was "oriented towards historicism and conservation":

"As though by a defensive reflex, the greater and more powerful our technological progress, the more timidly has our culture retracted to what it sees as the immutable and imperishable values of the past. . . . Thus the 'museum' has become the centre of musical life, together with the almost obsessive preoccupation with reproducing as faithfully as possible all the conditions of the past. This exclusive historicism is a revealing symptom of the dangers a culture runs when it confesses its own poverty so openly: it is engaged not in making models, nor in destroying them in order to create fresh ones, but in reconstructing them and venerating them like totems, as symbols of a golden age which has been totally abolished."

The consequences of this backward-listening attitude, Boulez argues, include the lack of invention in the making of musical instruments themselves, at least as far as the concert hall goes (it was a different matter "in a field like pop music where there are no historical constraints"; although pop music today has heritage issues of its own), and knowing what to do with techniques of "recording, backing, transmission, reproduction", which have "developed to the point where they have betrayed their primary objective, which was faithful reproduction". Classical music had reached a crossroads: a choice between "a conservative historicism which, if it does not altogether block innovation, clearly diminishes it" or a "progressive technology whose force of expression and development are sidetracked into a proliferation of material means which may or may not be in accord with genuine musical thought".

In the end, Boulez opts for a third way, trying to attain "global, generalizable solutions" rather than solutions "which somehow remain the composer's personal property". He could relish the chance that an institution such as IRCAM (which is not mentioned by name) offered him to explore the "geography of the sound universe", using the "reasoned extension of the material" to "inspire new modes of thought"; better this than recoil from the potentially "vast, chaotic and if not inorganic at least unorganized" field of electronics and computers.

Almost forty years on, some of Boulez's TLS essay may sound outdated; with the capacity for making electronic music available on your smartphone, perhaps it sounds itself like an emanation from a musical museum. Yet we might also say that the essay's central point ��� about a questioning awareness of artistic possibilities, defined by economics as much as critical orthodoxies, about creativity and the weight of history playing against innovation and the disciplined use of technology ��� still expresses a real challenge for all artists.

Reading Paul Griffiths���s account of those ninetieth birthday celebrations reminds me that the extraordinary thing about the ���extraordinary Boulez story��� is how completely he took up and lived out that challenge himself. His sense of progress had its enemies, of course: in 1996, on the transferral of the former culture minister Andr�� Malraux���s remains to the Panth��on, Boulez muttered publicly about the canonization of a man who had spent so much of his life ���dans les fum��es du whisky et l���opium���; presumably, Malraux���s dismissal of his plans for ���thorough reform of the state-run musical institutions���, thirty years earlier, had not been entirely forgotten.

How different things must have looked to Boulez in 1977, with the state-funded IRCAM open for business and the geography of the sound universe being mapped out before him.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers