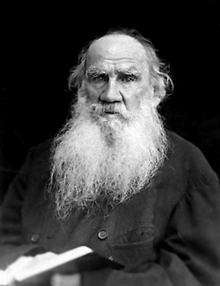

Summary of Tolstoy’s, The Death of Ivan Ilyich

Leo Tolstoy’s short novel,The Death of Ivan Ilyich, provides a great introduction to connection between death and meaning. It tells the story of a forty-five year old lawyer who is self-interested, opportunistic, and busy with mundane affairs. He has never considered his own death until disease strikes. Now, as he confronts his mortality, he wonders what his life has meant, whether he has made the right choices, and what will become of him. For the first time he is becoming … conscious.

The novel begins a few moments after Ivan’s death, as family members and acquaintances have gathered to mark his passing. These people don’t understand death, because they cannot really comprehend their own deaths. For them death is something objective which is not happening to them. They see death as Ivan did all his life, as an objective event rather than a subjective existential experience. “Well isn’t that something—he’s dead, but I’m not, was what each of them thought or felt.” They only praise God that they are not dying, and immediately consider how his death might be to their advantage in terms of money or position.

The novel then takes us back thirty years to the prime of Ivan’s life. He lives a life of mediocrity, studies law, and becomes a judge. Along the way he expels all personal emotions from his life, doing his work objectively and coldly. He is a strict disciplinarian and father figure, the quintessential Russian head of the household. Jealous and obsessed with social status, he is happy to get a job in the city where he buys and decorates a large house. While decorating he falls and hits his side, an accident that will facilitate the illness that eventually kills him. He becomes bad tempered and bitter, refusing to come to terms with his own death. As his illness progresses a peasant named Gerasim stays by his bedside, becoming his friend and confidant.

Only Gerasim shows sympathy for Ivan’s torment—offering him kindness and honesty—while his family thinks that Ivan is a bitter old man. Through his friendship with Gerasim Ivan begins to look at his life anew, realizing that the more successful he became, the less happy he was. He wonders whether he has done the right thing, and comprehends that by living as others expected him to, he may not have lived as he should. His reflection brings agony. He cannot escape the belief that the kind of man he became was not the kind of man he should have been. He is finally experiencing the existential phenomenon of death.

Gradually he becomes more contented and begins to feel sorry for those around him, realizing that they are too involved in the life he is leaving to understand that it is artificial and ephemeral. He dies in a moment of exquisite happiness. On his deathbed: “ It occurred to him that his scarcely perceptible attempts to struggle against what was considered good by the most highly placed people, those scarcely noticeable impulses which he had immediately suppressed, might have been the real thing, and all the rest false.”

Tolstoy’s story forces us to consider how painful it is to reflect on a life lived without meaning, and how the finality of death seals any possibility of future meaning. If, when we approach the end of our lives, we find that they were not meaningful—there will be nothing we can do to rectify the situation. What an awful realization that must be. It was as if Kierkegaard had Ilyich in mind when he said:

This is what is sad when one contemplates human life, that so many live out their lives in quiet lostness … they live, as it were, away from themselves and vanish like shadows. Their immoral souls are blown away, and they are not disquieted by the question of its immortality, because they are already disintegrated before they die.

Now consider an even more chilling question. What difference would it make if the life one lived had been meaningful? Wouldn’t death erase most, if not all, of its meaning anyway? Wouldn’t it be even more painful to leave a life of meaningful work and family? Perhaps we should live a meaningless life to reduce the pain we will feel when leaving it?

Summary – Confronting the reality of death forces us to reflect on the meaning of life.

____________________________________________________________________

Soren Kierkegaard, “Balance between Esthetic and Ethical,” in Either/Or, vol. II, Walter Lowrie, trans., (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1944).