Drinks before noon!

���The Worship of Bacchus��� by George Cruikshank (1860���62); Tate. Presented by R. E. Lofft and friends in 1869

By ANDREW IRWIN

It���s almost Christmas. And while there are stockings, turkey and mince pies to look forward to, the star of the show is obviously the rare acceptability of pre- (and post-) noon drinking. And so what would be more fitting for a grey December afternoon than a visit to Tate Britain���s BP spotlight, Art and Alcohol? According to Tate���s website, the one-room exhibition ��� curated by David Blayney Brown ��� ���examines the role of alcohol in British art from the nineteenth century to modern day���, as well as its ���catalytic effect���.

One might be forgiven for expecting an exploration of various artists��� relationship with alcohol as they sought Rimbaud���s ���d��r��glement de tous les sens��� ��� perhaps even an eager celebration of alcohol as inspiration, or a trigger for the Bacchanalian spirit of unbridled creativity. But no: what Tate presents is a whistle-stop tour through artists��� engagement with Britain���s changing views on alcohol.

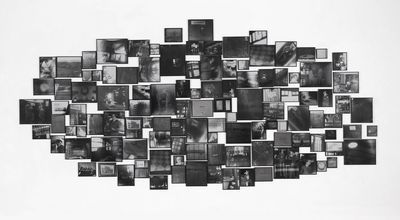

At the core of the show are two major pieces: George Cruikshank���s ���The Worship of Bacchus��� (1860���62) and, on the wall opposite it, "Balls: The evening before the morning after ��� drinking sculpture��� (1972), a multi-photograph installation by Gilbert and George. These two works, for all their dissimilarities in theme, tone and message, have a remarkable consonance.

Cruikshank���s is as didactic a work as one could imagine ��� a hellish image, in browns, blacks and greys, of a country overtaken by alcohol. The air is thick with smoke, and the top of the painting is lined with buildings ��� the police station, the lunatic asylum, the house of correction, alongside the brewery and distillery. At the centre is a statue of Bacchus; all around it revellers drink and dance, oblivious to the decay and poverty they leave in their wake. Other images crowd the scene ��� tableaux demonstrating the hypocrisy of a society whose very institutions are built on drink. As if Cruikshank feared his message too subtle, he has one man dancing on a tomb marked ���Sacrificed at the shrine of Bacchus���. The eye can barely settle, being drawn from scene to scene, face to face. A dour message, perhaps, but a dizzying spectacle.

Gilbert and George���s ���sculpture��� has much the same quality. Composed of 114 black-and-white photographs, all taken in the Balls Brothers Bar in Bethnal Green (London E2), the piece is a mimetic take on drunkenness itself. The photographs vary in both size and clarity ��� a fractured set of images on which it is difficult to focus before the gaze drifts. Hazy photographs of the artists, taken from uncomfortable angles, sit alongside images of the floor, a row of bottles, jocular bar signs, a decapitated body holding a glass ��� like an avalanche of grey, guilty memories.

"Balls: The evening before the morning after ��� drinking sculpture��� (1972) by Gilbert and George; Tate. Purchased in 1972

The other paintings in the exhibition include William Mulready���s ���Returning from the Ale-House��� (1809), in which two men amble drunkenly through a vibrant bucolic landscape; a group of children surrounds them. It is an almost affectionate portrayal, but when the painting was exhibited it met with public disapproval, and sold only in 1840, after the title was changed to ���Fair Time���.

David Wilkie���s ���The Village Holiday��� (1809���11) is similar in subject matter; but with its overcast sky and more muted colour palette, it seems less benevolent. At the painting���s centre, a man outside the tavern is tugged in both directions ��� on one side are his friends, clad in reds and blacks, pulling him back to the bar; on the other, his wife and child, in blue and white and cream, try to lead him away.

Robert Braithwaite Martineau���s ���The Last Day in The Old Home��� (1862) presents an aristocratic family on the verge of losing its ancestral estate (all dark woods and suits of armour). The husband blithely raises a glass, encouraging his son to do the same. Julius Caesar Ibbetson���s pair ���A Married Sailor���s Return��� and ���An Unmarried Sailor���s Return��� (c.1800) contrasts two scenes. In one, a seaman sits at a table opposite his wife, with his children and dog jostling for his attention. In the other, a bar full of women and dancing awaits him. The former, apparently, is the artist���s prescription.

The whole exhibition is curated as a series of binaries, nicely captured in Wilkie���s man torn between drinking and home. There is the shift from the artist as distant eye, passing judgement on others, to the artist as his own subject (as with Gilbert and George). And there is, naturally, the conflict between alcohol as benign pleasure and destructive vice. Something to consider, perhaps, on Christmas morning.

"The Last Day in the Old Home" (1862) by Robert Braithwaite Martineau; Tate; presented by E. H. Martineau, 1896

Art and Alcohol, a free exhibition, runs until autumn 2016.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers