Art as knowledge?

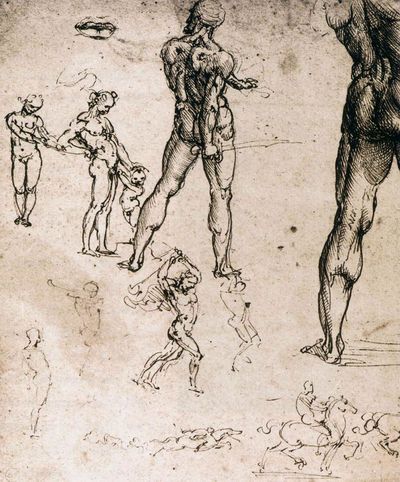

Leonardo da Vinci, figure study, 1505

By GABRIEL ROLFE

���Art as Knowledge?���, a discussion held at the London School of Economics last week, was the latest instalment in its now-twenty-year-old Forum for European Philosophy. The intellectual component in art, the climate of art���s reception and the social standing of the artist were all touched on, suggesting just how fertile this question is ��� even if the speakers kept their distance from an answer.

In the early Renaissance, painter and sculptor fought for inclusion in the so-called liberal arts. The theoretical writings of Leon Battista Alberti and Lorenzo Ghiberti gave unprecedented attention to the intellectual and inter-disciplinary knowledge required of the artist, which included philosophy and mathematics. In Leonardo da Vinci���s writings, we find the first exaltation of a unique knowledge belonging to the artist: the understanding of perspective. But the purview of this evening���s discussion was emphatically modern.

The chair of the discussion, Vid Simoniti, steered things with a playful off-handedness. He didn���t have much choice, settling down with an apology for the absence of Alexander Massouras ��� the panel���s sole practising artist was caught in traffic. Cottoning on to the sighs, Simoniti played it off as less disappointing than fitting ��� Plato had, after all, cast out the artist from his republic. But Aristotle took pity on the poor soul; and now here we were.

At this point, Matthew Kieran, Professor of Philosophy and the Arts at Leeds University, cleared his throat. He sketched for us an antagonist: the sceptic for whom art has no knowledge of its own whatsoever ��� it is simply telling us what we already know, from psychology, anthropology and science generally. Kieran almost lost himself in this dark ventriloquy, before reminding the room that, as an old-fashioned, paid-up humanist, he didn���t believe it. He pointed out a projection on the wall of the French artist JR���s "Women Are Heroes", in which eyes have been painted on the fa��ades of Rio���s favelas ��� the eyes of its female inhabitants. Conceding that the image may not impart any new knowledge as such, Kieran suggested that it made a kind of emotional understanding possible.

Neither he nor the audience seemed thrilled by this. Whether the ���emotional��� is a criterion for appraisal in itself was not pursued.

Kathleen Soriano, former director of exhibitions at the Royal Academy, brought a new image to bear ��� one central to the RA���s recent Anselm Kiefer retrospective, which she curated. "Ashflower" now hovered on the wall. Soriano relayed her experience of conceptualizing that show with Kiefer. She insisted that Kiefer���s intellectual ���seriousness��� ��� his monumental sublimations of history, poetry, philosophy ��� was both a tortured inward turn and an engagement with public discourse. But she agreed with Kieran that art consumes other knowledge, and ventured that, in exceptional instances such as Kiefer���s, art is capable of viscerally transmitting that knowledge into a ���common language���.

At this point, hands flew up in indignation. A flustered Kantian asked Kieran and Soriano to stop politely avoiding the business of aesthetics. With eerie ease, the panel offered their placation: ���some things are just beautiful���, and sure, art can be ���not about meaning���. Another audience member then decried the exclusive attention being given to the ���Western eye���.

A different energy wandered in with the belated panellist Alexander Massouras, painter and Leverhulme Early Career Fellow at Ruskin College in Oxford. His personal insistences were raw and winning. Of one of his own paintings, now being projected (from the series Nine flare paintings with octagonal aperture I, 2012���13), he recalled: ���I might have written an essay, but the ideas seemed more economically expressed in a painting���. Soriano interjected that there surely must have been a sense of the visceral, of the unthinking, to it. But Massouras either couldn���t or wouldn���t accept a distinction between an intellectual inspiration and the painting itself.

What Walter Pater once called ���true pictorial quality��� ��� the ���knowledge��� that physical, compositional elements such as form and line represent ��� remained disquietingly off the table. We are some way from the time when artists struggled to escape the standing of mere artisans. As Massouras matter-of-factly explained, the social imperative is now towards intellectualization, towards ���Theory���. And for the most part, the LSE Forum exemplified this. The artist���s struggle, then, is getting back to craft.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers