IT STARTED EARLY

You watch the tawdry spectacle of modern politics, and can only imagine with embarrassment what the Founding Fathers would think about it. Here’s an autocratic demagogue slandering foreigners, there’s a dysfunctional House of Representatives no one wants to lead, a circus of campaigns is railing against the media, and the politics of personality overshadow the issues of substance. What would the Framers of the Declaration of Independence say, those dignified patriots with their philosophical ideals? Actually, if they could peer into the future of today, they’d likely sigh and say not much has changed.

You watch the tawdry spectacle of modern politics, and can only imagine with embarrassment what the Founding Fathers would think about it. Here’s an autocratic demagogue slandering foreigners, there’s a dysfunctional House of Representatives no one wants to lead, a circus of campaigns is railing against the media, and the politics of personality overshadow the issues of substance. What would the Framers of the Declaration of Independence say, those dignified patriots with their philosophical ideals? Actually, if they could peer into the future of today, they’d likely sigh and say not much has changed.

Consider the elections of 1796 and 1800, which both pitted John Adams of Massachusetts against Thomas Jefferson of Virginia. You can’t get more Founding Father than that, two of the three members of the Declaration of Independence committee (Ben Franklin was the other). Was it a principled discourse on how best to achieve ordered liberty in a representative democracy? Not hardly.

By the end of George Washington’s two terms, the nation was already polarized into two political parties. Adams was a Federalist, Jefferson a Democratic-Republican. You can’t really line those parties up with modern Democrats and Republicans. Federalists, like today’s Democrats, believed in a strong central government, but also supported a large military budget and were somewhat conservative in adhering to the British model. The Democratic-Republicans, like modern Republicans, advocated small government and state’s rights, but also tended to be more idealistic and progressive. Regardless of the particulars, they fought like cats and dogs.

When Jefferson challenged Adams as excessively pro-British and monarchist, Adams made it personal by charging Jefferson as being too French and loose in character. Much as now, regional politics carried sway, with the northeast favoring Adams and the south Jefferson. Adams won the first election by a narrow margin, and under the rules of the day Jefferson as runner-up became Vice President. It was not an internally complacent administration.

When they ran against each other again in 1800, Jefferson got nasty. He retained a journalist to publish incendiary pamphlets attacking Adams, who retaliated in kind. It was a smear campaign that would make Lee Atwater blush. Adams was described as a “blind, bald, crippled, toothless man who is a hideous hermaphroditical character”; Jefferson was called the “mean-spirited, low-lived” offspring of a “half-breed Indian squaw” and a “mulatto father.” The Federalists were painted as anti-immigrant due to their support of the Alien and Sedition Acts. The Democratic-Republicans were depicted as bloodthirsty radicals sympathetic to French revolutionaries.

This time, the Democratic-Republicans won out, but Jefferson ended up with the same number of electoral votes as Aaron Burr. The battleground shifted to the House of Representatives, still controlled by the lame-duck Federalists. For thirty-five ballots there was gridlock. Finally Alexander Hamilton, the arch-Federalist and political enemy of both Jefferson and Adams, convinced his coalition to support Jefferson as the lesser of two evils. That’s why Aaron Burr is not on Mount Rushmore.

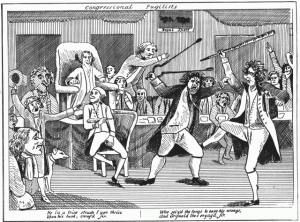

As a post-script to how hardcore the politics was in those days, Burr later, while Vice President, shot Hamilton dead with a gun. It sounds more dashing to describe it as a duel, but they shot at each other with handguns and Burr took out Mr. Ten-Dollar Bill. Can you imagine Joe Biden doing that to, say, Mitch McConnell? Burr was charged with murder, but was never prosecuted. The sensibilities of the times were sensitive enough, though, that his political career was over.

Yes, the process remains undignified, and unscrupulous, and at times downright detestable, and everyone is annoyed by attack ads, partisan media hysteria and snide personal insults. But at least the candidates are no longer shooting each other with guns in broad daylight. We’ve come that far.