A good death?

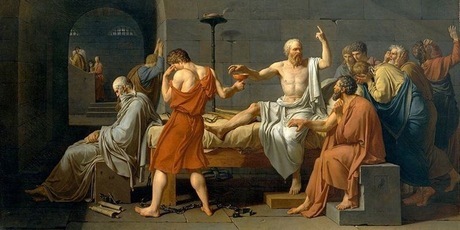

"The Death of Socrates" by Jacques Louis David, 1787

By WILLIAM REES

Perhaps it is fitting that the most interesting moment of A Good Death?, a symposium about death and dying which took place at Senate House last Wednesday, came towards the evening���s end. Professor Andrew Cooper of Tavistock and Portman NHS Trust, the fourth speaker to address an audience of about fifty, explained that while a few of us would die suddenly and unexpectedly, and a few peacefully, the majority of us would die slowly and incrementally, either of, or with, dementia. A gasp silently passed through the room.

Not that Professor Cooper paused to sigh or to laugh at our predictable response ��� already he was off, talking in his erudite, humane and generous way about the precarious communicative channels between the living and the dying.

The interdisciplinary event comprised four speakers: two experts on the ancient world and two on modern practice. Professor Eleanor Robson (of University College London) spoke about ancient Mesopotamia ��� in particular about the Epic of Gilgamesh, and the eponymous king���s struggles to understand mortality. Professor Robson had some interesting comments to make about the ���medicalization��� of death, a term that became a leitmotif for the evening, fluttering back and forth between the speakers.

Jumping forward a millennium-and-a-half, Professor Michael Trapp (of King's College London) spoke about Epicurus and Socrates, the two classical thinkers who have left the biggest imprints on philosophical ideas about death. For Socrates, philosophy itself is a preparation for death, and to die well is to die as oneself. For Epicurus, of course, all of that could be disposed with: one should not think too much about death: for as long as I am, death is not; and when death is, I am not.

On the face of it, these two positions are poles apart; are they not united, though, by their attempts to domesticate death ��� to control it, respectively, by staring it down or by turning away? It has never been clear to me that either has much relevance to the modern experience of dying, which is often very protracted, hardly ignorable and usually leaves us dispossessed of control long before the final dispossession.

But is the ���good��� death not anyway a rather suspect concept? This question, implicit in the title's punctuation, was taken up by Dr Mary Bradbury (of the British Psychoanalytical Society), who asked a startlingly simple question: for whom is the good death good? Dr Bradbury argued that the professionalization of death ��� what we might call the ���death industry��� ��� is an ambivalent development, both for the dying and for those they leave behind. In a crowded social context, with so many competing claims to what constitutes a good death (medical, (inter)personal, religious), would it not be wiser to search instead for a ���good enough death���?

Dr Bradbury left this question tantalizingly open; but it was taken up by the final speaker, Professor Cooper. The good death, he argued, is a distraction from the messier, more pressing issue of the oft knotty communication between those who are dying and those who are not yet. Impassioned but never moralizing, Cooper spoke about how our failure to rise to the challenge, to imagine more productive forms of communication that could take place between the living and the dying, led to those who are dying facing a ���social death���, which sometimes comes long before that other one.

The question-and-answer session that followed was, as is often the case, too short. After all, this is the one topic in which every person has a stake ��� a point cast poignantly into relief when a young boy, probably no more than twelve years-old, stood up and asked an eloquent and affirming question (about whether our obsession with what comes after death distracts us from life). As the evening came to a close, the accumulation of voices and perspectives pointed to how, far from being in conflict with or displaced by science, philosophy remains as important as ever. Advances in medicine have prolonged our lives ��� and our deaths. In doing so science has raised questions that it alone cannot answer; it has, in other words, breathed new life into philosophy���s ebbing relationship with death: a challenge to which philosophy must rise.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers