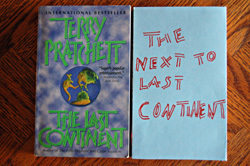

TT: The Next To Last Continent

JANE: The other day, when I was adding The Shepherd’s Crown to my shelf of Terry Pratchett novels, I saw The Last Continent. As I know you know, in addition to being a fun novel, it’s also a brilliant look at all the things that are characteristically – even stereotypically – “known” about Australia.

Uniquely New Zealand?

And suddenly I found myself wondering… Could Pratchett have done a sequel, called, say, The Next to Last Continent, about a Discworld New Zealand? Is there a National Type for New Zealanders or are they just like Australians?

ALAN: What a good question! Before I came to live here, like everybody else I lumped Australians and New Zealanders together. To me they seemed indistinguishable, in both their accent and their culture. I just thought of them as “antipodean,” and left it at that. But once I settled in and got used to how things worked, I began to realise that although the two countries do have a lot of similarities, there are some significant differences as well.

JANE: That’s fascinating! I definitely want to know more. Let’s start with the accent. How do people speak on “The Next to Last Continent”?

ALAN: The New Zealand accent has some peculiarities that really make it stand out from its Australian cousin. For example, New Zealanders have a very odd way of pronouncing some single syllable words – they tend to add syllables where none exist. So “known” and “grown” become “knowen” and “growen,” for example. And the word “no” has at least three syllables when spoken by a typical New Zealander, and I’ll swear that on occasion I’ve heard five…

JANE: Can you try to spell “no” as said by New Zealanders?

ALAN: Something like Naooohu. It’s a very odd sound indeed. I wonder what your spelling checker will make of that combination of letters…

JANE: It is puzzled. I am telling it to just put up with it!

ALAN: Conversely, there is a tendency to drop syllables out of multi-syllabic words. A certain very prominent New Zealand politician cannot actually pronounce the name of the country he helps to govern. It comes out sounding rather like “New Zlnd”.

JANE: Ah… An interesting contrast, however, not completely alien. At least when I was a kid – I don’t know if the accent has survived to now – Marylanders often said “Balmer, Merlin” for “Baltimore, Maryland.” Sounds like a magic spell…

Tell me more!

ALAN: New Zealanders also have a habit of turning declarative statements into something that sounds like a question, but isn’t. They do this by putting the word “eh?” at the end. So someone might say, “This is an interesting tangent, eh?” But despite the rising inflection and the question mark, it isn’t a question at all, it’s just a simple statement of fact. I’m told that Canadians do something similar, but I don’t know any Canadians, so I can’t be sure. Have you come across it? You are a lot closer to Canada than I am.

JANE: I have, although, here at least, the sound is usually given a long “a” sound, rather than the short “e” usually associated with “eh.” Which sound do New Zealanders use? Long “a” or short “e”?

ALAN: Definitely a short “e”.

JANE: You asked if I knew any Canadians. I do, in fact. My first editor, John Douglas, was Canadian. He’d lived in the U.S. for many years, but he said that whenever he went home to visit family, his accent would get “recharged.”

By contrast, author Charles de Lint and his wife, MaryAnn Harris, are both Canadian, and I don’t recall either of them using that characteristic verbal trick.

Maybe some of our Canadian readers – I know we have several – could weigh in and explain this for me.

ALAN: Good idea. When in doubt, consult the experts.

JANE: Your comment also makes me think about a tendency my husband, Jim, has, in his speech patterns. He doesn’t say “eh,” but he often ends statements with a rising inflection that turns them into a question. “Today we’re going to the grocery store,” can become a question.

This can drive me nuts, since we’ve usually discussed that we are indeed going grocery shopping, and I don’t know why he’s suddenly asking. Now I wonder if he was influenced by Canadian speech patterns. He grew up in a part of Michigan that is close enough to Canada that he could see it across the Detroit River, so this isn’t unlikely. A couple of the guys in his dorm were from the Iron Mountain area of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. He said that, based on their speech patterns, anyone would have thought they were Canadians.

I remember you mentioning that New Zealanders also shift vowel sounds. I bet that really complicates the situation!

ALAN: Yes, that’s an odd one. New Zealanders have completely lost the sounds of “a” and “e” – those sounds have slid over towards “i” and “o.” And of course “i” and “o” themselves have moved a bit in the direction of “u.” So “yes” becomes “yis” and “peg” becomes “pig”. If you go into a shop to buy a pin, you will leave with a writing implement.

Australians love to tease us by claiming, with some degree of truth, that New Zealanders dine on “fush and chups.” Mind you, Australians do funny things with vowels as well; they elongate them. Therefore I could easily get my own back by pointing out that Australians dine on “feesh and cheeps.” So there!

JANE: Yuck! Both versions create nasty mental images for me.

ALAN: But by far the most interesting effect of the vowel shift is that “woman” and “women” have become homonyms. Both are pronounced “woman” and you simply have to depend on context in order to figure out whether the singular or the plural is being used. Even after all the years that I’ve lived here, I still find this one very confusing.

JANE: Wait! You say they are both pronounced “woman,” but if you don’t use “a,” than the sound is more like “wo-min”? Am I right?

ALAN: Sort of. The sound is actually closer to “wo-mun.”

JANE: I’m beginning to be surprised that Roger and I could understand you people at all when we were there. Maybe you made a special effort. I do recall that Vonda McIntyre had become something closer to “Vondurr.”

ALAN: What makes you think that you understood us?

JANE: (choking with laughter). Maybe we didn’t! Still, we all managed.

I also wondered whether New Zealanders had odd words, like the Australian “bonzer.” (I think that’s right; I didn’t look it up.) There’s Pakeha, of course, which is a loan word from Maori that’s become part of general use, but are there others?

ALAN: We have a lot of Maori loan words of course (Pakeha is a perfect example), but we also have some constructions that are uniquely our own. If you wander around aimlessly, you are taking a “tiki tour.” Something that is broken is “munted.” When you are very angry, you are “ropeable” and when you are very happy, you are “stoked.” When you go swimming you wear your “togs.” If you want to take a quick look at something you will “have a wee squiz” at it. When you want someone to hurry up, you might tell them to “rattle your dags.” Are those odd enough for you? They certainly sounded more than a little peculiar to me when I first heard them.

JANE: Hmm… I’ve heard of “swimming togs.” We use that here, sometimes, but the others are completely alien and seem vaguely Scottish, somehow.

ALAN: Well spotted! Much of the South Island was settled from Scotland, and some of their colourful phrasing has made its way into the mainstream of day to day Kiwi conversation. “Wee” in the sense of small is a particularly good example and is very common.

JANE: I feel almost like a linguist!

We’ve certainly had fun with the language. I bet those language changes – especially some of the expressions you mentioned – reflect a cultural identity that’s distinct not only from the Australian, but from other nations as well. Maybe next time, you can tell me more about what makes New Zealand uniquely itself, rather than a shadow Australia.