Justin Trudeau’s Dad and Me

In Donald Brittain’s powerful 1978 television documentary The Champions, about the lifelong battle for Canada’s destiny between Pierre Trudeau and René Lévesque, there is a shot of Trudeau being interviewed in the midst of the 1968 Liberal leadership convention.

Days away from becoming prime minister, Trudeau is seated in a glass-walled TV studio in the midst of the convention. The camera pans around delegates and members of the media pressed against the glass for a look at this emerging phenomenon.

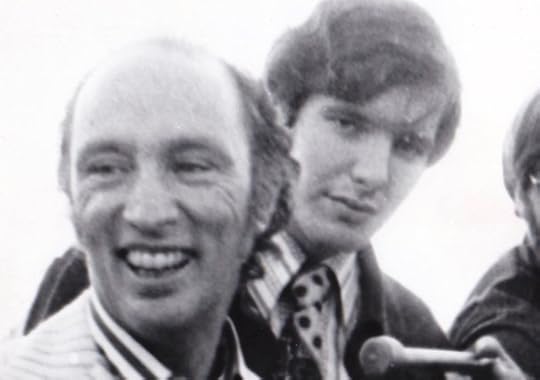

The panning camera comes to a stop and briefly focuses on a skinny kid in a trench coat fumbling with a camera.

That skinny kid is me, in grainy black and white, trying to take Pierre Trudeau’s picture. I must say, I am no better with a camera today than I was way back then.

To my amazement, I found Brittain’s documentary online (at the National Film Board’s web site). I sat watching it on my computer screen, fascinated all over again, not only by my (very) brief appearance but overwhelmed by the realization I have now lived long enough to witness not only the ascension of Pierre Elliott Trudeau into Canadian life, but now his son, Justin.

To view scenes from that convention all these years later as Justin Trudeau becomes prime minister of Canada is to be reminded how much we have changed in this country.

Today, as Pierre’s son takes power, I’ve become an old man, contemplating the end of things, not their beginnings. Back then I was just starting out, everything in front of me, a not-very-enthusiastic student at Ottawa’s Algonquin College journalism school. Somehow, our teacher, a quiet, patient man named Merv Kelly, had scored accreditation so our class could attend the Liberal convention.

I can’t imagine the press today having the kind of unfettered access we had that weekend at the Ottawa Civic Center. It seems to me we could wander just about anywhere, and rub shoulders with all the candidates, although, in truth, the only one that interested me was Trudeau. I trailed him around everywhere.

Friday night we all crowded into the lobby of Ottawa’s Chateau Laurier Hotel to hear the folk duo of Ian and Sylvia–very popular at the time–performing live. Suddenly, there was a stirring at the back of the lobby, followed by a wave of excitement as Trudeau appeared unexpectedly and was hoisted through the cheering crowd. If there was security, it wasn’t evident. There seemed to be only Trudeau up on a makeshift podium with Ian and Sylvia, making an impromptu speech, the crowd going crazy.

Friday night we all crowded into the lobby of Ottawa’s Chateau Laurier Hotel to hear the folk duo of Ian and Sylvia–very popular at the time–performing live. Suddenly, there was a stirring at the back of the lobby, followed by a wave of excitement as Trudeau appeared unexpectedly and was hoisted through the cheering crowd. If there was security, it wasn’t evident. There seemed to be only Trudeau up on a makeshift podium with Ian and Sylvia, making an impromptu speech, the crowd going crazy.

None of the other leadership candidates caused anything approaching this kind of excitement. They all seemed old and worn out. Trudeau, on the other hand, not unlike his son nearly five decades later, was new and exciting. No one had seen anything quite like him; he was a breath of fresh air in what was then such a staid and conservative country.

Anyone who looks back on those times and remembers the good old days probably didn’t have to live through them. It was a mostly all-white society, in many ways still under the colonial shadow of Britain (Canada had achieved its own flag amid much rancor only a couple of years before). The white men who ran the country closed everything up tight on Sundays. You could not even go to a movie.There were still separate tavern entrances for men and women.

If you wanted to buy booze, you went to the government-operated liquor store, filled out a form, signed your name, and then took it to the counter and handed it to a clerk who then disappeared behind a partition to reemerge minutes later with your purchase in hand–in a plain paper bag, so no one would know you were a shiftless drunkard.

Everything was overcooked and bland. There were only a few decent restaurants and eating out was still considered a special event. In retrospect, Trudeau’s major achievement other than repatriating the constitution from Britain, may have been opening the flood gates to immigration, thereby making it possible to get a good meal in this country.

Books such as Peyton Place, James Joyce’s Ulysses, and Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer were banned outright in many quarters. In Toronto, people went to jail, literally, for displaying art that was considered pornographic.

The first time I encountered Trudeau, I was still in high school. Our Brockville Collegiate Institute class came to Ottawa to tour the Parliament buildings–you could just walk into the place back then.

We were supposed to meet with John Matheson, our very popular Liberal member of parliament (probably the last time Brockville ever elected a Liberal). However, Matheson, whom I admired tremendously, was ill that day. He did speak to us over the phone, though, and said he was sending a close friend to substitute for him.

In walked Pierre Trudeau, who was, at the time, Minister of Justice. What did I think of him that day? Was I mesmerized by the man who was soon to lead the country? Not at all. I thought he was boring.

But not at the convention a couple of years later. By then, Trudeau was electrifying the country. Those of us who were part of that time never quite lost our affection for him or forgot the sense of excitement he brought to dull Canadian life. As most Canadian politicians do, he over stayed his welcome, and, as has been the case with President Obama in the U.S., the reality of Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau never quite lived up to the promise of the sports car-driving, movie star-dating young maverick (not so young after all; it turned out Trudeau was forty-eight when he was elected leader of the party).

I won’t be so melodramatic as to say that weekend at the Liberal convention changed my life. But certainly much changed that year. A couple of months later, school behind me, I was a reporter working for a daily newspaper, The Oshawa Times, while Pierre Trudeau crisscrossed the country in his first election campaign as prime minister, mauled by huge crowds everywhere he went. Trudeaumania was in full flower.

My first day at work I was preparing to cross the street to the Times when I glanced around and saw a lanky, bald-headed man standing on the corner. I realized with a start that this was Robert Stanfield, the leader of what was then called the Progressive Conservative Party, the guy running against Trudeau to be prime minister. I couldn’t believe it. He was all alone, not a soul around him. I went over and shook his hand, understanding at that moment Stanfield didn’t stand a chance in the election. And, of course, he didn’t.

Much has happened since Pierre Trudeau stepped into Canadian life, both to me and to the country. Now, as Justin Trudeau becomes Canada’s second-youngest prime minister, I suppose there is a certain closing of the circle.

I wonder if Justin would like his picture taken.