Return to HOWL

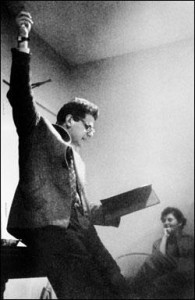

Allen Ginsberg reads at the Six Gallery in San Francisco, October 7, 1955.

Every time I think I'm out, they pull me back in. Last year it was William S. Burroughs' hundredth birthday celebrated by a European Beat Studies Network conference in Tangier. This year it's the sixtieth anniversary of Allen Ginsberg's first reading of Howl in San Francisco. I'll be in Brussels for the ESBN conference commemorating that event, performing a Ginsberg-themed piece as part of The Muttering Sickness. I don't even like the Beats, I keep telling myself. I'm not an angst-ridden teenager any more. I'm old enough to see through their genius for self-promotion, the easy recuperation by the culture of their attack on the forces of patriarchy, conformity, and capitalism. (Spontaneous Bop Capitalism, we ought to call it.) Kerouac wore khakis, Burroughs was a lowlife, Ginsberg wrote three or four indelible poems and was otherwise a bearded self-referential embarrassment. What keeps me coming back?

It's personal. When I posted that photo on Facebook, someone commented that it looked a lot like me. And while I don't have the genes to become bald or grow a beard, that simple fact--that as a young poet I could find so easily an image for myself reflected in the world--meant something.

Just look at the guy. You can see the charisma, but in spite of the black and white and the cigarette or roach he's smoking, there' s nothing cool about those glasses, the intensity of the gaze, the shockingly sensuous mouth. If Ginsberg embarrasses he embarrasses by his warmth and vulnerability and nervous joy in living. His words and image made it possible for my younger self to imagine that my inability to be cool, to live indifferent and defended, might not mean my automatic and inevitable destruction.

Or rather, that it might be possible to live with the knowledge of destruction. For Ginsberg is one of the most-death haunted poets I know. It's all over Howl and of course it's the reason for being of Kaddish, an unbearably personal poem, not least for me because my own mother, although far from mad, exhibited qualities of depression and narcissism that marked me for life, and then of course she died young, as it happens less than a mile from the "The mental hospital--state Greystone," one of the several grim palaces where Naomi Ginsberg was treated for her mental illness. (It's also where Woody Guthrie spent his last years losing the battle with Huntington's; Bob Dylan famously visited him there.)

When Ginsberg addresses Carl Solomon in Howl, when he says, "I'm with you in Rockland," he's really talking to his mother. She is the muse he cannot deny, who terrifies and threatens him, the possessor, in Allen Grossman's formulation, of "an insane idealism of which her son is heir" (Long Schoolroom 154), and for whom he musters a truly astonishing compassion. In one of the most uncanny passages of Kaddish he embraces, almost literally, the stench of mortality and sadness that has come to surround her flesh, as it surrounds all flesh, though we pretend not to smell it:

One time I thought she was trying to make me come lay her—flirting to herself at sink—lay back on huge bed that filled most of the room, dress up round her hips, big slash of hair, scars of operations, pancreas, belly wounds, abortions, appendix, stitching of incisions pulling down in the fat like hideous thick zippers—ragged long lips between her legs—What, even, smell of asshole? I was cold—later revolted a little, not much—seemed perhaps a good idea to try—know the Monster of the Beginning Womb—Perhaps—that way. Would she care? She needs a lover.

Yisborach, v’yistabach, v’yispoar, v’yisroman, v’yisnaseh, v’yishador, v’yishalleh, v’yishallol, sh’meh d’kudsho, b’rich hu.

Birthdeath, "the Monster of the Beginning Womb," revolted only "a little, not much," followed by the Hebrew that only comparatively late in life am I beginning to get a feel for, if not comprehension of: Blessed and praised, glorified and exalted, extolled and honored, adored and lauded be the name of the Holy One, blessed be He. Something I say, or ought to say, every December 21, on the anniversary of my own mother's death.

As with Ginsberg, my mother represents a portal to the incomprehensible cruelty of the past. In Naomi's case, she is haunted, sometimes comically, by the specter of Adolf Hitler--"she saw his mustache in the sink." My own mother was herself a Holocaust survivor, born in Budapest in 1942, hidden with her grandparents in the ghetto while her own parents, my grandparents, Ernest and Eva Montag, were sent to Auschwitz. Miraculously, both survived, and returned to Hungary to collect their little girl, and spent a few years in the British DP camp in Bergen Belsen before emigrating to this country, where she grew up in the long shadow of her parents' trauma, in Queens.

Fifty years ago, in the summer of '65, incessant traveler Ginsberg managed to get himself kicked out of two socialist countries in succession (Cuba and Czechoslovakia), as he writes in a long and entertaining letter to the legendary antipoet Nicanor Parra. He also, in passing and by the way, paid a visit to Auschwitz, a visit summed up in one peculiar sentence in his letter to Parra: "Then a week in Krakow which hath a beauteous cathedral with giant polychrome altarpiece by medieval woodcarver genius Wit Stoltz, and car ride to Auschwitz with some boy scout leaders who were trying to pick up schoolboys hanging around the barbed wire gazing at tourists." This borders on bad taste: is the perpetually horny Ginsberg unable to notice anything at the camp other than the vaguely predatory behavior of the "boy scout leaders" he is inexplicably traveling with? And who the hell was Wit Stoltz? Google turns up only Ginsberg's letters and, if you don't use quotation marks, footage of Eric Stoltz as Marty McFly in unused footage from Back to the Future.

On Sunday, October 25, sixty years after Howl and fifty-six years after Kaddish and fifty years after Ginsberg made nothing, at least nothing obvious, of standing on the ashen ground of Auschwitz, and eighteen years after Ginsberg's death in New York, I will visit Auschwitz-Birkenau for the first time. Although Ginsberg had already written the poems on which his reputation stands by the time of his own visit, there is a case to be made that those poems are saturated by the experience of the Shoah, as processed through the ambiguous relation of an American Jewish poet to that experience. Allen Grossman puts it this way:

The characteristic literary posture of the postwar poet in America is that of the survivor—a man who is not quite certain that he is not in fact dead…. ’Since so many like me died, and since my survival is an unaccountable accident, how can I be certain that I did not myself die and that America is not in fact Hell, as indeed all of the social critics say it is?’ Ginsberg’s poetry is the poetry of a terminal cultural situation. It is a Jewish poetry because the Jew is a symbolic representative of man overthrown by history. (153)

Grossman goes on to claim that "Ginsberg's chief artistic contribution in Kaddish is a virtually psychotic candor that affects the mind less like poetry than like some real experience that is so terrible that it cannot be understood. In America, which did not experience the Second World War on its own soil, the Jew indeed may be the proper interpreter of horror" (157). That "virtually" is interesting because what we have here are paired and opposed virtualities: the virtuality of "the bitter logic of the poetic principle" (poetry's effacement or erasure of the actual in its pursuit of representation) versus "virtually psychotic candor," a break not with representation but with reality itself. Kaddish, in other words, comes as close as any (American) poet can to presenting something like the unrepresentable horror of the war, something which can otherwise only be given in the testimony of survivors, the only discourse unbarred by the Adornian dictum "To write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric."

Implicitly or maybe explicitly, Grossman criticizes Ginsberg and other American poets for reducing the disasters of the twentieth century to the personal. But what other ground does a fundamentally lyric poetry (and I believe that Ginsberg is a lyric poet, in spite of the length of his most famous poems) have to work from? Put another way, I feel myself as a poet and writer forever trying to reconstitute the conditions that ground my imagination and its powers, however limited. I've dedicated at least one novel to trying to reimagine, from a skewed perspective, the mental life of my mother; in another novel I'm imagining the moment my parents met; in yet another project I use the Heidegger-Arendt affair as a kind of ground zero moment of the twentieth century but project it into the twenty-first, so as to make the resources we've developed around the problem of the unimaginable (in history) available for imagining the future.

For me there's no getting away from Allen Ginsberg; poetically speaking he's my gay grandfather, mon hypocrite semblable, whose drolly encompassing prosody seems to promise, as Grossman suggests, not a description of experience but experience itself. A kind of wit matched with the darkest recesses of experience, intended not to aggrandize the self but which makes the lyric I into the imperiled traveler (a drunken boat) we all are.

Standing on that bare ground, in Poland, my head bathed by the smokeless air, I will encounter neither Allen nor my grandparents nor the angel of history but sheer contingency, fragility, the monster of beginning, that which enables fate.