The honey harvest: A tutorial.

All year, in the back of our minds, it’s “how are the bees coming along?” and “Will there be a honey harvest?” Because first you keep them (and hope they don’t fly off or die) and then you check the honey (and hope there’s enough for them and us).

And they did so well this year, we got new ones as well, and we had the harvest!

My dear husband Phil, the Chief, is guest posting to tell you how it all went. We tried to be as specific as possible, so that you could picture it all in your minds. There are many places on the interwebs you could go to get info about bees. But I know you all like to hear us say it anyway.

With no further eloquence, here’s Phil!

On the beekeeping calendar, the happiest day of the year is harvesting day, when we bring in the season’s crop of honey. Would you like to walk through it with me?

The process begins a few days before the actual harvest day. But to help you understand, I’ll need to take you back much further.

My bees live in two brood boxes, where for most of the season the queen lays and the workers work, packing in pollen and honey. Once I’m confident that they have enough food stored for the winter, I add another box, called a super, in which they will collect surplus honey—just for us! [The blue ones on the left are supers ~ L]

The bees build their comb in the super, then gradually fill the comb with nectar. When that nectar is fully converted to honey—after the bees have reduced the moisture content to perfection—they cap the cells with a thin layer of wax. And when I see frames full of capped comb, I know it’s harvest time.

A few days before I plan to harvest, I put an escape board under the super. This ingenious device is probably my favorite piece of beekeeping equipment. It’s a board with a hole in the middle, and a simple maze underneath. When a bee goes down through the hole, she’ll run into a wall. If she turns to the left, she’ll go back to the super; if she turns right, she’ll go down into the brood box.

But here’s the thing:

When honey bees encounter an obstacle, they always turn to the right!

So within a day or two, most of the bees have left the super, clearing it out and making it ready to harvest.

On harvest day, I pull the super off the hive. It’s heavy! When I first put it on top of the brood boxes, full of empty frames, it weighed just a few pounds. Now it’s probably more than 50 pounds. That’s a good sign. After carefully brushing off the frames to remove the few remaining bees, I bring them indoors, and we’re ready to harvest.

We prefer to harvest in the evening, for a couple of reasons. First, when the sun goes down the bees go to bed, so they aren’t attracted by the smell. (We’ve tried harvesting in the daytime, but it’s unnerving to have bees constantly pinging off the screen windows, attracted by the powerful smell of the honey.)

Second, it’s a great time to have a few friends over, to enjoy the occasion and help crank the extractor.

The extractor is basically a centrifuge. Once the wax cappings are sliced off the frames, we whirl them around in the extractor. The honey is thrown to the sides, collects at the bottom, and then is drained out and strained. This year, because we were harvesting on an unusually cool evening, Auntie Leila thought to wrap the extractor in an electric blanket, to warm things up and make the honey flow a bit faster. Did it make a difference? I’m not sure. [I also got out the blow dryer to pump warm air in the extractor. Don’t know if it helped. ~ L]

It’s a long, laborious process. (That’s one reason why it’s nice to have different people taking turns, cranking away.)

A friend once observed that Mother Nature provides us with many different sources of sugar, but one way or another, we have to work for it. We spin and spin and spin and spin, check the frames, turn them around, and spin some more. It’s a messy, sticky business, too; you won’t want to wear your silk scarf. But licking the honey off your fingers isn’t exactly a hardship!

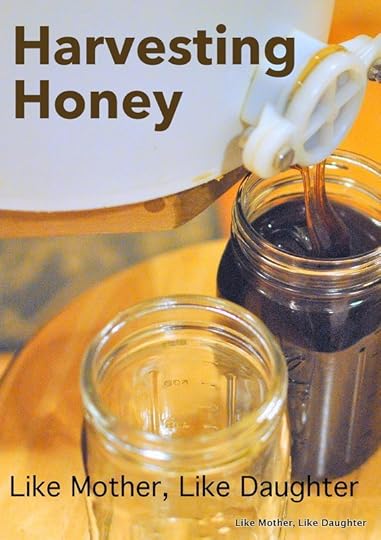

And when we finally open the tap (called a “honey gate”), and the elixir begins to flow out into the bottling bucket, it’s a beautiful moment.

This year’s product was a rich, very dark honey. Once we hit our stride, it just kept flowing. By the time we were finished there would be well over 3 gallons, or 40 pounds of the precious stuff.

We don’t sell our honey—we’re not in this for the money [I’d be happy to sell but so far we don’t get enough! ~ L] —but we should have enough to last us until the next harvest (and certainly enough to last until spring, when we’ll be harvesting our maple syrup), even after setting aside jars for family and friends.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. After the honey has been spun off the frames, it still needs to be strained, to separate out the bits of wax and pollen. We use two sieves, one finer than the other. Then Auntie Leila takes the waxy sediment caught in the filters, as well as what we’ve scraped off the frames, and after any remaining honey has dripped off, boils it down. (While she’s doing this, the entire house is suffused with a subtle, inviting smell of honey and wax.)

This produces two products: a disk of pure beeswax (pictured here still wet from the bowl), which we’ll mix with oil and use for polishing furniture and cutting boards; and a bowl of watery honey, which she’ll reduce and use for cooking. Finally, we use boiling water to clean out the extractor and bottling bucket. That water, too, is added to the pot to reduce.

There’s one more step in the clean-up process. All those frames, once thick with capped honey, are now sad sheets of torn-up wax with stubborn drops of honey still clinging to the cells. Fortunately I have recruited some volunteers to help clean them up. About 50,000 volunteers, in fact: the bees themselves. I put the ravaged frames back on top of the hive. The bees will eat the honey, clean up the wax, and within a day or two the frames will be ready to store for the winter and put back on the hive for next year’s harvest.

The post The honey harvest: A tutorial. appeared first on Like Mother Like Daughter.