Roll, Jordan, Roll: A Book Review

A self-professed communist, who got kicked out the Communist Party, included his Marxist viewpoint of American slavery in “Roll, Jordan, Roll.”

Roll, Jordan, Roll, The World the Slaves Made, winner of the 1975 Bancroft Prize, is indispensable to understanding American slavery in the antebellum South. It’s also delightfully controversial in history and content.

It was written by Eugene D. Genovese , a communist later turned conservative. He was in his Marxist phase when he wrote it, and he tried to squeeze his image of slavery into his perspective of ideological class conflict and exploitation. I found his communist theorizing for the most part easy to ignore, though tedious at times, but I appreciated his comparisons of slaves in the Old South with workers and slaves and their circumstances around the world. Some readers, however, thought his social theories devalued Roll, Jordan, Row.

Roll, Jordan, Roll: A Theory of Paternalism

Other reviewers have complained Genovese wrote of slavery as one Goodreads reviewer claims focusing “on slavery as a system of paternalism. It tries hard but in its efforts reduces slaves to one dimensional caricatures who have bought into and welcome the system of slavery.” I can’t imagine we’re thinking of the same book.

But it’s not just casual reviewers have who disputed the book’s perspective: In its obituary for the author, the New York Times noted “historian Edward L. Ayers . . . called it ‘the best book ever written about American slavery'” while historian Eric Foner held that “the buying and selling of slaves could hardly be considered paternalistic; parents do not normally sell their children.”

Sounds to me like a semantic disagreement.

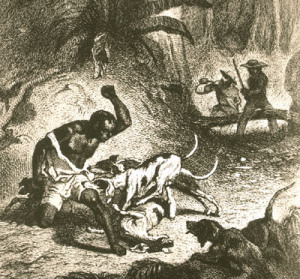

“Row, Jordan, Row” notes specially trained dogs, often owned by poor whites, tracked runaways, maiming and killing if not pulled quickly from the escaping slaves.

Genovese does write extensively in Roll, Jordan, Roll about paternalism but never suggests slaves bought into or welcomed the abominable social order or system. There was never a doubt in my mind that the complete wrongness of slavery in all its forms under-girded Genovese intent and work in the book. To me Roll, Jordan, Roll did exactly the opposite of what such detractors claim. It portrays a range of slaves and slave experiences, always presenting the victims as individual human beings under unbearable circumstances. His major premise is slaves individually and collectively created meaningful lives and community, stubbornly refusing to adopt slaveholder will as their own. As Genovese writes:

Slavery, a particularly savage system of oppression and exploitation, made its slaves victims. But the human beings it made victims did not consent to be just that; they struggled to make life bearable and to find as much joy in it as they could. Up to a point even the harshest of masters had to help them do so. The logic of slavery pushed the masters to try to break their slaves’ spirit and to reconstruct it as an unthinking and unfeeling extension of their own will, but the slaves’ own resistance to dehumanization compelled the masters to compromise in order to get an adequate level of work out of them.

In this quote, I hear criticism of slaveholders and their dehumanization of slaves in their pursuit of wealth—a legitimate attack on the capitalism of the antebellum past North and South which conspired against Africans stolen from their homelands. In no sense does the quote above, which captures the spirit of the tome, hold that slaves approved of or passively accepted their state. When the author wrote about slave revolts (or lack of them), he reprises the theme:

In the United States those prospects [of revolting], minimal during the eighteenth century, declined toward zero during the nineteenth. The slaves of the Old South should not have to answer for their failure to mount more frequent and effective revolts; they should be honored for having tried at all under the most discouraging circumstances.

As time went on those conditions became steadily more discouraging: the hinterland filled up with armed whites; the population ratios swung against the blacks; creoles [I believe he uses creole in the sense of American born] replaced Africans; and the regime grew in power and cohesion. . . . Meeting necessity with their own creativity, the slaves built an Afro-American community life in the interstices of the system and laid the foundations for their future as a people. But their very strategy for survival enmeshed them in a web of paternalistic relationships which sustained the slaveholders’ regime despite the deep antagonisms it engendered.

The slaves’ success in forging a world of their own within a wider world shaped primarily by the oppressors sapped their will to revolt, not so much because they succumbed to the baubles of amelioration as because they themselves were creating conditions worth living in as slaves while simultaneously facing overwhelming power that discouraged frontal attack.

Neither quote suggests to me a view of slaves as willing, docile human beings accepting happily their state, willingly ceding their independence and will to the slaveholder. But the author also is not presenting a simplistic view of slavery that offers all slaves as heroes and all slave owners as despotic. In his work, Genovese portrays a complex system where players (some better than others) by choice and others without choice work for their own purposes, exacting as much as they can from the other side.

Roll, Jordan, Roll depicts slaveholders consciously manipulating the feelings and loyalties of their slaves to their own purposes. Included in those manipulations is granting “privileges” as one-time “gifts” to slaves, but the slaves successfully seized many such privileges, claiming them as rights for the future, thus bettering as best they could their living conditions. Over time, this give and take developed into recognized, “accepted” traditions. Thus “masters had the upper hand, but slaves set limits as best they could” in a series of horrible compromises. Such a view seems consistent with the complexity of all human relations and therefore appears credible.

Clearly, however and unfortunately, both master and slave consciously or unconsciously bought into a paternalistic relationship and strengthened it by their respective behavior based on masters generally taking responsibility for clothing, feeding and protecting (not necessarily well) and slaves coming to expect it. This led to some slave owners believing their own propaganda and feeling betrayed by the “lack of gratitude” slaves showed when they would run away or had the audacity to leave the plantation or farm after the war or Union army freed them.

Varied Voices

For me, the best aspect of Roll, Jordan, Roll was Genovese’s use of quotes from slaveholders and slaves across the wide array of topics covered, offering varied voices and circumstances to create a broader, more textured understanding of the state of slavery in the South.

I also appreciated the book’s discussion of the development of an ironic style of communication among slaves. They didn’t have the freedom to speak the truth so they developed the ability to speak “undercover,” saying at times the opposite of what they meant. Roll, Jordan, Roll never gives us a stereotypical slave as fool, while it does capture slaves sometimes playing the fool to manage masters, some of whom understood and at times appreciate the theater and some who become the fools by not recognizing the manipulation.

Another appreciated aspect of Roll, Jordan, Roll was revelation of the flexibility of the slave work calendar. Sometimes we’re left with the impression slaves were worked 14-16 hours a day constantly for years on end, always leaving one wondering how they could survive. That was the lot of some slaves in other countries in the hemisphere where they were literally worked to death. But in the American South, master self-interest meant slaves generally were not required to work such long hours in all weather conditions year round. During specific seasons and activities, such as cotton harvest, they did labor exceptionally long days. But that was, Genovese suggests, the exception. That’s not to imply slave life was pleasurable because of a “shortened” work day as forced labor and hours are wrong and miserable on any scale. But it presents a more realistic perspective on work hours.

Roll, Jordan, Roll is dense, long (nearly 700 pages; over 800 with notes) and complicated. It covers a wide expanse of topics, including religion, law, work and work conditions, freedmen, mammys, runaways, love, sex, drivers and overseers, marriage, the elderly, children, cooking and funerals. (Researching the last topic is why I picked up the book in the first place.) Necessarily some topics aren’t covered in as much depth as I would have liked. But the book is a major accomplishment and a unique contribution to our understanding of the world the slaves made. In the end it is an indispensable tribute to what slaves were able to achieve in spite of being forced to play a rigged game of chance.

Mr. Genovese great labor enriched my understanding of the awful institution of slavery in the South.

Nod to transparency: Some members of my family descend from slaves held in the US and one family of ancestors held—based on census records—two slaves, a young woman and a boy under 10.

The post Roll, Jordan, Roll: A Book Review appeared first on Michael J. Roueche.