TWO VIEWS ON THE OREGON TRAIL

When I was in school, Francis Parkman’s The Oregon Trail was on my reading list. At the age of thirteen, the formal writing and the lengthy, detailed descriptions of a time, scenery and people who did not in the least interest me, turned me towards another choice of book. So here I am, some fifty years later, with other interests, more tolerance, and certainly a more receptive mind.

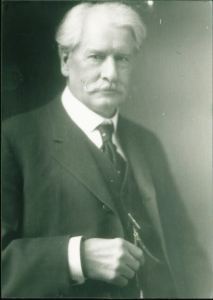

Francis Parkman

Francis Parkman was born into an aristocratic Boston family, son of a well-connected and wealthy Unitarian minister. Plagued by illness most of his childhood, he was often sent into the countryside in an attempt to make him more robust. This, combined with his own enjoyment of James Fenimore Cooper’s novels, seems to have had a lasting effect on the young man whose walks in the woods always entailed carrying a rifle, just as his hero, Hawkeye, did. At Harvard, his interest in Native Americans became evident, and his desire to write histories of the United States (as well as a love of horticulture) took root. Taking time off from college to do a Grand Tour of Europe in order to recover from one bout of his neurological illness, he visited George Catlin’s Indian Gallery in London. This may have been the final push to form plans to travel west. In May, 1846, he finally set out for Independence, MO, with his equally well-heeled cousin, Quincy Adams Shaw. The duo went on to Fort Laramie where, under the sponsorship of the American Fur Company, they were outfitted and prepared for their journey to live with the Oglalla Sioux. Parkman even dressed for the part of a westerner, kitting himself out with buckskins sewn by the Oglalla women at the fort. Years later, he still possessed the outfit when Frederic Remington prepared the illustrations for the deluxe 1892 edition of Oregon Trail.

As anyone who has read The Oregon Trail will know, Parkman pushed himself through many bouts of illness, dosing himself with opium to plod on. In the end, he lived with the Oglalla for three weeks, taking copious notes that eventually formed the book. Parkman would return to Boston where he wrote numerous histories of the United States as well as becoming a professor of horticulture at Harvard, and a founder member of the Archaeological Institute of America.

The Oregon Trail was to have a great influence on the minds and hearts of

Emigrants on the Oregon Trail

Americans. Consider that it still appeared as recommended reading for my school in 1964, and that editions are readily available today. And how many writers of western material or television scriptwriters have taken Parkman’s word and descriptions to heart?

So what is so captivating about The Oregon Trail that it has lasted this long? Parkman was very much a product of his class and times. For someone who was so intent on living with the Native Americans, he is singularly unsympathetic to their plight or their lives, repeatedly referring to them as “mongrels.” Yet while the modern reader may be rightfully appalled at these and other appellations, there is a certain fascination in how prescient Parkman’s writing is: on pg. 90 he describes a wagon train rolling past a native village: “a long train of emigrants with their heavy wagons was crossing the creek, and dragging on in slow procession by the encampment of people whom they and their descendants, in the space of a century, are to sweep from the face of the earth,” and later “…the buffalo will dwindle away, and the large wandering communities who depend on them for support must be broken and scattered. The Indians will soon be abased by whiskey and overawed by military posts…” (pg. 190) Parkman saw this as the natural march of progress much as missionaries see bringing Christianity to indigenous inhabitants a step toward civilization.

Julius Birge

Some twenty years after Parkman’s journey, Julius Birge left his Wisconsin home to take virtually the same trip. He, too, kept notes, and forty-five years later, in 1912, these would be the basis for The Awakening of the Desert. Also descended from an old New England family, Birge, while not as formally educated as Parkman, was still incredibly well-read and had also suffered illness. One of the reasons he took the trip, which was to ostensibly deliver goods to a Mormon settlement, was to recover from a bout of typhoid. But Birge had grown up in rural Wisconsin amid Pottawattamies and Winnebagos; indeed, he was reputedly the first child ever born to non-native parents in Whitewater, WI. Because of this, Birge’s interests are totally different from Parkman’s, and, perhaps, also because of this, his judgments are gentler. However, both men dealt with Native Americans and both encountered Mormons; both men spent time at the forts along the route and both lighted upon almost identical scenery. They each had treacherous river crossings and knew hardships and thieves. In 1872, in the introduction to the fourth edition of The Oregon Trail, Parkman reassessed his view of that march of progress. He wrote, “…we did not dream how Commerce and Gold would breed nations along the Pacific, the disenchanting screech of the locomotive break the spell of weird, mysterious mountains…had we foreseen it, perhaps some perverse regrets might have tempered the ardor of our rejoicing.” Birge also had the benefit of hindsight; in 1912, some forty-five years after his journey, he knew that such an advancement, more than anything, also marked the end of “…the country as God has made it…” and that western migration was “…depraving and demoralizing even the savages.” (pg.56) His view was that, “the cities and states of America have struggled to increase their population by immigration, apparently on the theory that the rate of that increase was to be the measure of growth in the happiness and prosperity of its people. When our national heritage shall have been partitioned among the nations of the earth, and the wild, wooded hillsides shall have been denuded by axe and fire, giving place for farms and cities, then those whose fortune it has been in childhood to roam through the primitive forests or over the yet free and trackless plains, would hardly exchange the memories of those years for a cycle on the streets…” (pg. 56)

The Oregon Trail by Alfred Bierstadt

I can only wonder why he saw the desert—that great American ‘desert’, the plains—as awakened. It might have been more apposite to say that it had begun its death throes. But how apt his words are today.

The Oregon Trail at South Pass today

The editions I used for this post are:

Birge, Julius C. and Birge, Barbara B., The Awakening of the Desert: An Adventure-Filled Memoir of the Old West, a CreateSpace 2014 reprint of 1912 edition, Gorham Press, Boston This book is also available at Audible.com For further information, go to http://theawakeningofthedesert.com

Parkman, Francis, The Oregon Trail, Dover Publication, Inc., Mineola, NY, 2002, reprint of 1883 edition, Little, Brown, and Company, Boston.

Parkman, Bierstadt and b & w Oregon Trail photos Public Domain; photos of Julius Birge and South Pass, courtesy of Barbara Birge