Jesus: Unethical and Unwise

On Sunday 27th I’ll be giving a short talk in LA called “Jesus: Unethical and Unwise.” The reason for my interest in this subject is that, from the very beginning of Christianity, there has been a strong desire to see the figure of Jesus as a moral teacher or wise man. While this is especially obvious in progressive circles today, one even sees it taking place in more conservative communities. Parables are explained, sayings are viewed as insights, disturbing or contradictory ideas are massaged and reformulated to become coherent and sensible ethical teachings.

It was this approach to Jesus that sent Kierkegaard’s blood pressure through the roof. For him, Jesus was anything but wise, and the Christian faith was a spear thrust into the side of ethical thinking. He even spent an entire book, Fear and Trembling, exploring how the founding event of the Hebrew scriptures was impossible to grasp from the point of view of ethics and wisdom.

Kierkegaard was baffled about how the story of an old man obeying a voice inside his head telling him to kill his kid, could possibly be domesticated by religious professionals.

In protest, he disturbs his reader by getting them to think long and hard about how unethical and just plain stupid this act was.

What ethical teacher would tell a man to obey some inner voice telling him to kill his wife?

What wise guru would counsel a woman to poison her husband because she received a sign?

I don’t want to delve into Kierkegaard’s fascinating reading of Abraham and Isaac here, except to draw out how any progressive attempt to render bible stories like this one into some kind of wise and ethical text will always result in intellectual gymnastics, bad faith arguments and embarrassment.

If you are outside of the Islamic, Jewish or Christian traditions you might simply ignore the story, but what do we do if this story is fundamental to our tradition?

To approach an answer to this we can simply reflect on what happens when someone relays a dream in therapy. The dream is accepted by the analyst as reflecting something fundamental about the subject. It touches on some central conflicts, desires, fears etc. The dream might be nonsensical, disgusting, evil etc. but the analyst neither rejects it nor simply accepts it at face value. Rather she takes it very seriously and helps the one in analysis (the analysand) to discover something about themselves in it. A process that can be profoundly transformative.

The point of a psychoanalytic interpretation is not to make sense of the dream, to make it fit within the culturally acceptable wisdom of the day, or to domesticate it. It is there to help the analysand become surprised at themselves, disturbing their everyday understanding of their desire, and bring hidden traumas to the light of day.

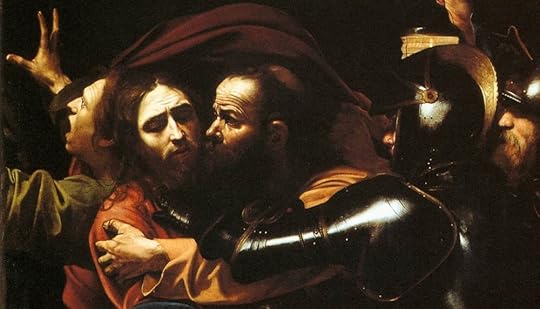

To turn briefly to the little we know of Jesus, we discover that his primary means of communication is one that disturbs and surprises his listeners. He speaks in a way that confounds the beliefs and practices of the day and, in doing so, brings up tensions, violence and traumas that were previously lying unseen. His discourse, as I explore in The Orthodox Heretic, was a type of dis-course designed to send people off-course and onto a new course (something that has strong links with the meaning of ‘repentance’).

The problem I have with the idea of theological interpretation being concerned with making sense of obscure and disturbing elements of the text has a parallel to the crisis that occurred in psychoanalysis whenever psychoanalytic interpretations became better known to the general public (post WWII).

What therapists were finding was that individuals would come to the clinic with quite thoughtful and potentially accurate readings of why they did a certain thing, e.g. I find it hard to trust woman because I was abandoned by my mother.

The problem was that the interpretations were not actually evoking transformation. It was Lacan who argued that psychoanalysis had gone off track in thinking that interpretation in the therapeutic setting was about making sense of something. Rather it was more to do with disturbing and surprising the analysand, with bringing things to the surface, with reliving the past in the present within the theater of analysis etc.

In the same way I would argue that Progressive Christianity has taken a wrong turn in attempting to make the bible (or the ‘red letters’ of the bible) into some kind of ethical teaching or set of wise aphorisms.

This is the theological equivalent of CBT. A process that can be helpful in making small adjustments to ones life, but that doesn’t touch on the reasons for our symptoms, and doesn’t help us work them through at the level of the unconscious.

Instead we should interpret the parables and sayings of Jesus in ways that make them strange again, that cut against our understanding, and that bring hidden institutional traumas to the surface.

Why?

For the same reason that one does this in therapy. Because, in doing this work, we discover the dead parts of ourselves, the hurt parts, the angry and lonely parts. In bringing those to the surface as a community we will let them heal by touching fresh air, warmth and light. And, if we are patient, the results will be seen in communities more alive to the other, more involved in making the world a better place, more gracious, more loving, and more joyful.

Peter Rollins's Blog

- Peter Rollins's profile

- 314 followers