Off The Reservation – Chapter 1, Part 1

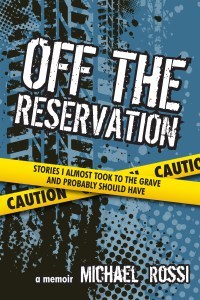

This is the next post in my ongoing plan to share as much of my memoir; Off The Reservation: Stories I Almost Took To The Grave And Probably Should Have, as I can.

This published memoir starts with childhood, but the original version I wrote did not follow chronological order. I attempted to deviate from the standard sequential format of biography to create a cause and effect description of my life. I almost immediately discovered that the great friends who agreed to be guinea pigs for my first draft had a hard time following along, so I changed the format.

I realize now that I was not yet skilled enough to take my readers along the path I desired, but I still believe that my story’s chain of circumstances is the most important aspect that you won’t find written in the book. It is my hope that some of you see it anyway.

CHAPTER 1

CARS, CATS, AND OTHER LIVING THINGS

The three of us leaned forward in the seat and whispered in unison. “Sledgehammer,” we said softly but maniacally toward the car’s vents.

After letting the threat of violence sink in for a moment, my father’s girlfriend Heather slowly turned the key in the ignition for a second time. This struggle was commonplace for the old Ford—a perfect mixture of blue and rust, with a white vinyl top so severely cracked as to give it a marble appearance. I had no understanding of cars as status symbols and what this one said about our family. To me, it was a fantastic machine, a giant blue whale of steel and glass. It had great big white pleather bench seats and came complete with a hole in the floor on the passenger side, where rust had eaten all the way to open air. Through this hole, one might watch the asphalt whiz by or drop an errant French fry or piece of candy when nobody was looking. I laughed a villainous chuckle as each victim disappeared through my trap door.

The obstinate Ford failed to start for a second time, and the wind-up was slowing, threatening back at us a dying battery. My sister and I both sat on the bench front seat, our seatbelts completely ignored, listening intently to the cranking of the starter for any proof of life.

I was six, short and thin with a giant mop of unkempt curly blond hair and blue eyes. On my skin I wore my annual coat of poison ivy, covered in dull pink calamine lotion. I was every kid in a movie that takes place in California in the early seventies, but upstate New York was as far from California as you could be.

My sister Amy was ten, much taller, a giant really. Unlike me, Amy was embossed with all of the traits of our Sicilian father: dark hair, dark eyes, and olive skin. She was every girl you ever saw in a movie about New York; she fit in.

I was always jealous of my sister’s familial dark features. Blond-haired, blue-eyed children have a tendency of standing out awkwardly in Italian family photos. I am only half-Italian, as is my sister, but we couldn’t look more different. The sight of us with our father made you wonder if perhaps there was a Swede hiding in the woodpile.

Amy and I are only half-Italian, but we were both mostly raised by whole Italians of different degrees. How Italian you are can be easily determined by how many Italian words you pepper into your everyday speech. My grandparents spoke only Italian when they were alone. Their children knew the words but only spoke it to their parents, and I don’t speak the language at all. I do actually know a little. If you would like to be called lazy and stupid, and then in four different ways be told in no uncertain terms that it would be completely acceptable for you to go and fuck yourself, I’m your guy.

Although our first two attempts to start the car had failed, I was somewhat relieved. All I could think of was the inspection under the hood we always had to do when we visited Heather’s family farm. It was imperative that you examine the motor compartment before leaving, because one cat had already died after crawling into the engine of a parked car in that driveway. Despite all of the farm’s wonders, visits meant being haunted by the idea of an angry car engine turning a cat into burger.

I was traumatized by the thought. The image of a poor, defenseless, bloody cat wrapped around a fan blade preoccupied my thoughts every time a car started. If it took two or three tries to start the car, so much the better. Maybe a trapped feline might use those moments to escape and thus save itself.

“Junkyard… Scrap metal… Trash heap.”

We all knew that whispering threats to the cantankerous Ford was the only way to get it to start, everybody in the family did. The triple dose of intimidation worked like a charm, and as the vehicle sputtered to life, we pulled from the driveway with all the animals alive and well.

I really don’t know why I was so concerned about the cats. My allergies had already swelled my face, and I was sure to wake the next morning with my eyes sealed shut thanks to our visit to the upstate New York farm and its many creatures.

I am very allergic to cats—so allergic, in fact, that they could literally be weaponized against me. Many years later, I would marry a woman who hated me with such ferocity that I would arrive home from work one day to find she had gone to the pound and adopted a little brown one out of spite. She held it close to her face and smiled at me menacingly over the fur as I came walking through the door, but that is a different story.

The glorious New York farm we were leaving was home to Heather’s parents. They weren’t farmers at all but mechanics, and instead of fixing plows in the barn, they built the best racecars in New York, or so I was told. Heather’s father Bud was a renowned driver and mechanic—famous thanks to his legendary string of wins on the New York stock-car circuit when he was young. Bud was the perfect combination of simple, gruff, and satisfied that you never meet in a city. After he hung up his gloves but before his sons were old enough to race, Bud built fantastical machines in his garage for other drivers.

The men would stand around in the barn all night, every night after dinner, to work on the racecars and drink beer. They drank Miller High Life but often discussed their common grievances about not being able to drink Coors—well, not in New York anyway. Thanks to the movie Smokey and the Bandit, which started the rumor that the beer was illegal east of the Mississippi, as well as poor distribution policies by Coors, New York beer drinkers of the late seventies and early eighties would often create elaborate conspiracy theories as to why the libation was not readily available.

The farm was surrounded by apple orchards, overrun with cats, and home to a pet skunk. It even contained a real hen house. Whenever I spent the night there, I would try to wake up before the rooster and go as close to the coop as I would dare stand so I could hear his first call to rise. Just so you know, in case you have never experienced it, chickens are fucking vicious.

In the summer and fall I would eat green unripe apples from the orchard and blackberries off the stone wall that bordered it until my stomach was in knots and my skin covered in poison ivy. Small but delicious strawberries grew wild on the side of the road; it was a magical place.

This was the summer of my seventh birthday, and I didn’t know much, but I knew that cars had souls, and ours lived in fear of the many possible punishments we threatened it with. I also knew that cats, unripe fruit, and the three-leaved plants they both hid behind were bad for me no matter how much I loved them. I will spend the rest of my life learning that there are a great many so-called cats to be love/hated, and not all cars are fearful.

I lived with my sister Amy, my father Michael, and his girlfriend Heather in the sleepy town of Fairport, New York, a small village along the Erie Canal waterfront. It was kind of a dump when I lived there, but it has become a haven for hip, happy white people since then. As a child, the only thing I liked about Fairport was the lift bridge, which hardly lifted at all.

New York summers exist in such stark contrast to its bleak winters that survival needs to be built into the character of its buildings and people. Both are constructed to be strong enough to endure the cold and snow, but soft enough to enjoy warmth and fruit. Growing up in New York means you have a deep respect for spring and the promise it brings.

My mother, Debbie, had left us a couple of years earlier—or at least it felt like years. Debbie had been raised in the poorest suburbs of St. Louis, and gotten pregnant by my father shortly after they got together. Three years later, after moving to New York, my parents decided to get married because they had accidentally gotten pregnant again, with me. The Supreme Court had ruled abortion constitutional about six months before my mother became expectant with me, so I am sort of happy they decided not to be trailblazers in the matter.

To be continued…

Post Script: When new people I meet discover that I have written a memoir, one of two statements is made. The most common response is more of a narrowing of the eyes, than a statement. They are unaware that some of the best memoir writers in the world are regular people; not famous people. The other response comes from those persons that believe that they too have a book inside of them. Some memoir writers become irritated by this question; I have read so on their blogs. They feel as if the statement somehow diminishes what they have written, because somebody believes it easy enough to do themselves. This is horse-shit. If you think you can write a book about your life you should at least try. What’s the worst that could happen? Jenny McCarthy has written nine books, and she is an idiot.