Banned Books Month Guest Post from Ann McMan: I Am Spartacus

I’ve spent the better part of six decades trying to connect the dots.

During that time, I’ve had some modest success. The pictures that emerged were pretty good, and frequently entertaining. Creating them was a lot like indulging in a real life version of the iconic Highlights magazine puzzle. Once I got a pirate ship. Another time I thought I could make out the figures of two young girls, drifting on inner tubes down a river of fire. That image was akin to one of those standard psychological tests—the ones where you’re asked to describe what’s taking place in an ambiguous photograph.

“I see Mommy hitting Daddy on the head with an axe.”

“I see Mommy hitting Daddy on the head with an axe.”

I was always pretty good at those, too.

Enter writing. Telling stories became a lifeline for me—a rope ladder that I could use to haul myself out of the muck and emotional moribundity that lined the sticky pit of my life.

I didn’t want to burnish my chains—I wanted to break them.

So I told stories. A lot of them. And even though I sometimes allowed myself to wander off the paved roads that traversed the landscape, I mostly confined myself to roaming The Known World. It was safer there. Friendlier. I know where I was going and when I’d get there. I even had maps. And there were featured attractions along the way. Quirky things—like roadside restaurants that came equipped with handy phone apps so I could transmit my orders in advance of arrival.

Nifty. Neat. No surprises.

Hamlin Garland called these literary highways Main Traveled Roads. They’re comfy. We recognize them. We know every dip and sag in the pavement. We have our favorite rest stops all picked out—and we can linger over those as long as we choose. They’re familiar. They’re safe. And they don’t scare or challenge us.

But what happens when we stumble across something that does challenge us? That does threaten the bastions of what Toni Morrison called the temples of our familiar?

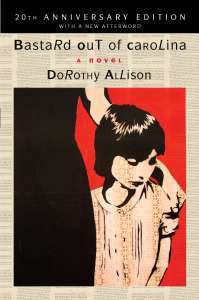

Plume; Reprint Edition, February 2012.

Chaos ensues. We panic. We circle the wagons. We vow to protect our children. We collude in our ignorance and fear and we conspire to silence the voices of authors who dare to disturb our pretty peace. And one of the best weapons in our arsenals is the ability to ban the books they write. We label them as obscene—or too graphic, too violent, too rife with harsh content that is inappropriate for children.

Dorothy Allison’s novel BASTARD OUT OF CAROLINA didn’t enter my life; it exploded in the middle of it. Allison is an irreverent prophet. A bombastic soothsayer. An unapologetic teller of truth. A teller of my truths, as it turned out. Because her story about Bone, a feisty 11-year-old girl who survives a childhood predicated by emotional, physical and sexual abuse was also my story. I always knew my own truths, of course—but it had never occurred to me that giving voice to them would offer me a kind of freedom that I’d never known before. Learning that there were other girls like me—like Bone—gave me permission to speak my own truths, and the courage to understand that calling my own demons by name was the only way I could derive them of their power.

Unfortunately, not everyone shared my epiphany.

BASTARD OUT OF CAROLINA, Allison’s first novel, was a finalist for the National Book Award in 1992. It has been celebrated by literary critics as “close to flawless.” Allison has been hailed as one of the finest writers of our generation. Yet this semi-autobiographical novel that dared to speak the truth about family violence and incest soon found a home on the banned books list in multiple states.

The power of BASTARD OUT OF CAROLINA is both emotional, and political. “The novel is mean,” Allison says, “meant to rip off all that facade of imagination and lies we place around sexual violence and children.”

Not age appropriate. That’s what they said about it. “The story is too graphic in its depictions of sexual violence against children.” One enterprising school administrator in California even suggested, “there are characters [in other books] out there that go through rape and abuse that have better endings.”

I guess “better endings” are always considered more age appropriate. Unhappily for me and at least one-in-four other girls growing up in America, those “age appropriate” stories didn’t much parallel the real lives we went home to after school. But then, we were encouraged to maintain our vows of silence because our lives—like the banned books that dared to describe them—were considered unfit topics for public discourse.

“I had imagined my novel would be a catalyst for clarity and compassion,” Allison wrote in her afterword to the 20th anniversary edition of BASTARD OUT OF CAROLINA, “not an impetus to anger and repression.”

In her memoir, TWO OR THREE THINGS I KNOW FOR SURE, Dorothy Allison explained that her job as a storyteller was not to make anyone happy. “What I am here for is to claim my life, my mama’s death, our losses and our triumphs, to name them for myself.”

But for me, the damage of Allison’s nearly perfect prose had already been done. Her words surrounded me. They resonated in my ears. Pounded in my viscera. Her truth filled up my world. And it reached down inside me to that secret place where my own truths lay hidden in their endless half-sleep—always with one eye open. She saw me. She knew me. And she called me out.

“In the writing,” she explained, “I had thought that if I get this right, I can change so much—how people think about rape and child abuse, and working-class families and the nature of resilience, and even perhaps something about how love can both save us and not save us. But also in the writing, I had thought that there was no way to get anything that right. All I could really do was tell a story the best way I could and hope to nudge some people’s notions a little more toward understanding what still does not make sense. Why would anyone beat a child? Why would anyone rape a child? Older and full of the world’s experiences as I am, I still do not know the answer to these questions.”

I don’t know the answers either. But I do know that silencing the voices of the prophets has never served us well. Education isn’t simply about rote memorization and the blind assimilation of facts. Learning requires analysis and critical thinking. Learning involves socialization and learning how to function in a complex society. Students are always better served by reading about diverse topics in a rich environment that encourages honest discussion. Safe and guided venues for thoughtful examinations of uncomfortable or controversial topics are essential to help young minds develop the cognitive skills needed to survive in an increasingly brutal and chaotic world.

“What banning books does,” Allison explained, “is continue the denial, extend that damage, and block any way for us to come together and address the reality of violence within our families and communities. We know this even as we go on wanting a world in which we do not need to tell these stories at all.”

Bywater Books, December 2015.

I am a teller of stories. I am a survivor of incest and domestic violence. I am Spartacus.

Daring to read this courageous banned book saved my life.

Writer Dorothy Allison taught me that to be my best self, I must be willing to tell the truth. I must be naked on the page. I must learn to reveal myself, and the things I’ve learned, in the stories I tell. If I don’t, I shortchange my readers. If I don’t, I waste their time. If I don’t, I embrace shame and secrecy and not life.

“My daddy was a son of a bitch, and my mama didn’t love me.”

I tell stories to live, she said. I tell stories to survive.

Maybe that school administrator in California got one thing right—sometimes, if we dare to speak the truth, there can be better endings.

Ann McMan.

Ann McMan is the author of five novels, JERICHO, DUST, AFTERMATH, HOOSIER DADDY, and FESTIVAL NURSE, and the short story collections SIDECAR and THREE. She is a recipient of the Alice B. Lavender Certificate for Outstanding Debut Novel, and a two-time winner of the Golden Crown Literary Award for short story collections. Her novel, HOOSIER DADDY, was a 2014 Lambda Literary Award finalist. Bywater Books will release her semi-autobiographical novel, BACKCAST, in December of 2015.