WHEN TRUNKO MET NESSIE?? - PARADOX OF THE PICTISH BEAST

Line diagram of the Pictish beast (public domain)

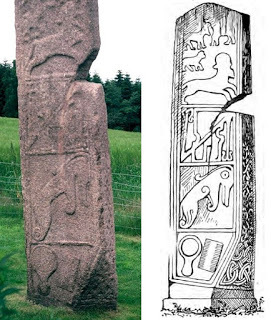

Line diagram of the Pictish beast (public domain)Named after their very distinctive body tattoos, the Picts ('painted people') inhabited northeastern Scotlandas a separate tribe from c.300 AD to 850 AD, after which they were united with the Celtic Scots under the reign of King Kenneth I. The Picts can boast as their principal claim to archaeological fame their ornately-carved symbol stones. These are elaborately decorated with various creatures, objects, and other depictions, especially the earlier, pre-Christian stones - which are designated as Class I (dating from the 6th Century, generally unshaped, and bearing line-incised symbols on at least one flat face) or Class II (of rather later date, and bearing much more intricate, flamboyant designs). Class III stones, conversely, date from when Christianity reached the Picts, so on these stones the earlier Pictish symbols have been mostly replaced by Christian ones.

Due to their realistic designs, the many different animal types carved on Class I and II Pictish symbol stones are readily identifiable – with one notable exception, that is. Appearing on about 29 Class I stones and 22 Class II stones, this bizarre-looking exception is known as the Pictish beast.

Close-up of Pictish beast depicted on Meigle 4 Stone at Meigle Sculptures Stone Museum (© Simon Burchill/Wikipedia)

Close-up of Pictish beast depicted on Meigle 4 Stone at Meigle Sculptures Stone Museum (© Simon Burchill/Wikipedia)Several very famous Pictish symbol stones bear depictions of it. These include: the Dunfallandy Stone (Class II) in Tayside; one of the Rhynie Pict stones in Aberdeenshire; and the 6-ft-tall Rodney's Stone (Class II), which is a cross-slab of grey sandstone originally present in the graveyard of the old church of Dyke and Moy but subsequently transferred to the Grampian village of Dyke to commemorate Admiral Rodney's victory and standing today on the left side of the avenue leading to Brodie Castle.

Other symbol stones depicting the Pictish Beast are a cross-slab on the Brough of Birsay at the northwestern corner of Mainland, Orkney; the 9th-Century, 10-ft-tall Maiden Stone near Pitcaple in Aberdeenshire; and a carved stone in Grampian's Port Elphinstone Henge near Inverurie (the henge itself is much older than the carvings). Perhaps the least stylised, most 'natural' portrayal of this mystifying creature can be found upon a spectacular Class II stone at Tayside's Meigle Sculptures Stone Museum, which is adorned with carvings of horse riders and a tail-biting serpent as well as the Pictish beast, plus the customary Pictish V-rod and crescent symbols.

Pictish beast depicted on Meigle 5 Stone at Meigle Sculptures Stone Museum (© Simon Burchill/Wikipedia)

Pictish beast depicted on Meigle 5 Stone at Meigle Sculptures Stone Museum (© Simon Burchill/Wikipedia)Depictions of it on such symbol stones as these portray this bizarre creature with a dolphin-like head, a long beak, four limbs that often curl backwards underneath its body (although sometimes, as on the Meigle Museum stone, only the paws curl backwards), an elongate tail with a noticeable curl at its tip, and, most distinctive of all, what may be a long slender horn or even a trunk-like projection sprouting from the top of its head and curving over its back. Indeed, this last-mentioned feature has earned the Pictish beast the alternative name of 'swimming elephant' (which all too readily conjures up some decidedly surreal images of a Celtic version of Trunko! - click here to read all about this latter onetime monster of misidentification).

Needless to say, no known species of animal resembles the Pictish beast as so portrayed, which in turn has incited appreciable speculation and controversy among historians and archaeologists as to what it may be. One popular, conservative identity for it is a dolphin (or even a beaked whale, i.e. a ziphiid), based upon its beaked, superficially dolphin-like head - as a result of which I wonder if its anomalous 'trunk' may in reality be a representation of a spout of water spurting upwards when the dolphin exhales through its blowhole (conjoined, modified nostrils), which is indeed situated on the top of this marine mammal's head. Conversely, the unequivocally leg-like limbs and non-fluked tail of the Pictish beast are radically different from the flippers and fluked tail of dolphins and other cetaceans.

Pictish beast depicted on Rodney's Stone at Brodie Castle (© Ann Harrison/Wikipedia)

Pictish beast depicted on Rodney's Stone at Brodie Castle (© Ann Harrison/Wikipedia)Other postulated suggestions include a seahorse (especially when depicted vertically), a deer, a seal, and a dragon. A bona fide elephant or even an unknown species of secondarily aquatic elephant has also been considered (albeit not seriously, for obvious reasons!). It may simply be that the Pictish beast is an entirely fictitious, imaginary creature, possibly even a composite of several different creatures, but its numerous portrayals (accounting for approximately 40 per cent of all Pictish depictions of animals) imply that it had considerable symbolic significance for the Picts.

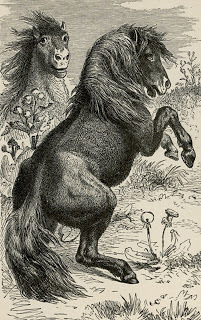

Indeed, it may even be the earliest known artistic representation of the legendary kelpie or Scottish water-horse (click here for a ShukerNature article on this malevolent entity). One of the three Aberlemno symbol stones in Tayside depicts a pair of interlaced horse-headed, elongate aquatic monsters, and some scholars have suggested that these may constitute a more sophisticated version of the Pictish beast.

A rearing kelpie – is this the identity of the Pictish beast? (public domain)

A rearing kelpie – is this the identity of the Pictish beast? (public domain)Moreover, in their book Ancient Mysteries of Britain (1986), Janet and Colin Bord proposed that the Pictish beast might be a direct representation of the elusive water monsters allegedly inhabiting various of Scotland's lochs, its 'trunk' explaining the familiar 'head and neck' or 'periscope' images often reported and even photographed by Nessie eyewitnesses. Backing up their fascinating hypothesis, the Bords make the following very telling observation:

"Since a whole range of animals and birds is accurately depicted on the symbol stones - wolf, bull, cow, stag, horse, eagle, goose - perhaps these were the creatures most familiar to the Picts in their everyday world, and 'monsters' were also familiar to them, being more often seen in the lakes than they are today, and accepted as part of the natural world just like eagles and stags."

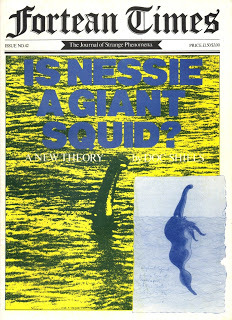

This in turn leads to the most intriguing and original (if zoologically offbeat) identity ever put forward for the Pictish beast. A familiar figure in the British Fortean community for many years, Tony 'Doc' Shiels describes himself as a monster-hunter, stage magician, surrealist artist, and shaman of the western world (among other things), and he has suggested that the Pictish beast may indeed be a depiction of the unidentified Scottish water monsters. Moreover, as he first documented in a Fortean Times article (autumn 1984) and further propounded six years later in his book Monstrum! A Wizard's Tale (1990), and as I have also referred to briefly earlier in this present book (see Chapter 7), he has speculated that these latter mystery beasts' zoological identity could in turn be a highly novel, specialised form of squid.

Front cover of Fortean Times #42 (autumn 1984), depicting 'Doc' Shiels's conjectured elephant squid at bottom-right (© Fortean Times/Tony 'Doc' Shiels)

Front cover of Fortean Times #42 (autumn 1984), depicting 'Doc' Shiels's conjectured elephant squid at bottom-right (© Fortean Times/Tony 'Doc' Shiels)But how could such a creature be equated with Nessie and company, and how firm are its basic anatomical and physiological foundations? Here is what I wrote about Shiels's proposed 'Pictish squid' in my book Mysteries of Planet Earth (1999):

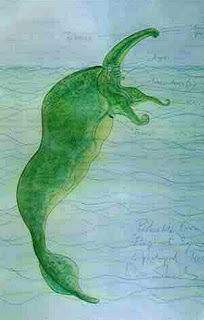

"As conceived by Shiels, the most striking feature of his hypothetical species is a long, flexible, prey-capturing proboscis-like structure (the trunk of the Pictish beast), on account of which he has dubbed this creature the elephant squid. If held out of the water, its proboscis could resemble a long neck, which Shiels believes may explain the familiar 'long-neck' images of Nessie and her kin. He also provides his elephant squid with inflatable dorsal airsacs as part of its buoyancy mechanism (which could yield the varying shape and number of humps reported for Nessie), six short tentacles, and a pair of longer curling arms (the Pictish beast's curling front legs), as well as a muscular tail bearing two horizontal lobes.

"In his accounts, Shiels proposes that this remarkable mollusc may even be able to emerge briefly onto land, which might therefore explain why certain Nessie eyewitnesses (such as the Spicers, who claimed to have spied this mystery beast on land in 1933) have likened it to an enormous, hideous snail. Quite apart from the profound morphological modifications necessary for a beast corresponding to Shiels's elephant squid to have evolved from known cephalopod (squid and octopus) stock, however, a fundamental obstacle to this hypothetical creature's plausibility is that all known species of modern-day cephalopod are exclusively marine. There is not a single species of freshwater squid or octopus on record, and for one to evolve would require drastic tissue modifications relating to osmoregulatory ability."

Doc Shiels's sketch of his hypothetical elephant squid (© Tony 'Doc' Shiels)

Doc Shiels's sketch of his hypothetical elephant squid (© Tony 'Doc' Shiels)Shiels's Fortean Timesaccount attracted considerable interest within and beyond the Fortean and cryptozoological fraternity, and summaries of his speculation subsequently appeared in a wide range of publications by other writers. Regrettably, however, many of these second-hand accounts mistakenly claimed that Shiels had formally dubbed his hypothetical elephant squid Dinoteuthis proboscideus (translating, incidentally, as 'trunked terrible squid'). In reality, conversely, as Shiels went on to explain in Monstrum!, Irish zoologist A.G. More had already given that particular name to a massive squid specimen beached at Dingle in County Kerry, Ireland, in October 1673 during a major storm. Instead, Shiels suggested that an apt name for his own, totally conjectural cephalopod would be Elephanteuthis nnidnidi - a name that needs no explanation for anyone knowing of Shiels's experiments with psychic automatism.

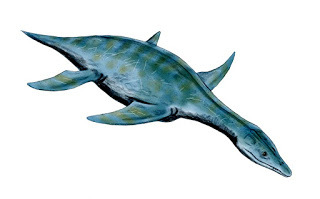

More recently, mystery beast researcher Scott Mardis from the USAhas suggested that the Pictish beast images may actually depict an evolved, surviving species of short-necked plesiosaur (and therefore quite probably a pliosaur, which also had long jaws like those of the Pictish beast). Plesiosaurs have of course been officially extinct for at least 64 million years, but an evolved, surviving representative of the long-necked, short-jawed version (elasmosaur) of these aquatic prehistoric reptiles nevertheless has long been a popular cryptozoological identity for Nessie-type water monsters.

Leptocleidus capensis

, a short-necked, long-jawed plesiosaur from the early Cretaceous (© Nobu Tamura/Wikipedia)

Leptocleidus capensis

, a short-necked, long-jawed plesiosaur from the early Cretaceous (© Nobu Tamura/Wikipedia)In short, the Pictish beast remains the subject of several interesting interpretations, but no satisfactory solutions - unless of course the answer lurks not among its petroglyphic portrayals but instead within the secretive depths of the lochs forming a major, familiar part of the landscape once inhabited by the painted people of Scotland's distant past?

This ShukerNature blog article is excerpted from my forthcoming book Here's Nessie! A Monstrous Compendium From Loch Ness .

Pictish beast depicted on the east side of the Maiden Stone in a photograph (© Ronnie Leask/Wikipedia) and a line drawing (public domain)

Pictish beast depicted on the east side of the Maiden Stone in a photograph (© Ronnie Leask/Wikipedia) and a line drawing (public domain)

Published on September 13, 2015 12:53

No comments have been added yet.

Karl Shuker's Blog

- Karl Shuker's profile

- 45 followers

Karl Shuker isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.