Reading Ta-Nehisi Coates in South Africa, Part 3

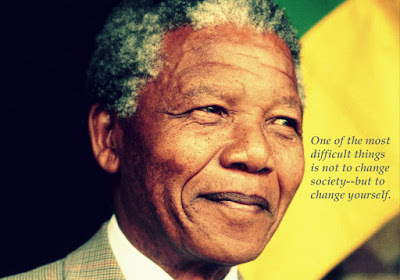

A man with a self-proclaimed beautiful smile

A man with a self-proclaimed beautiful smileOne of the things I really liked about Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Between the World and Me was its focus on the body as the operating symbol of the African American experience…past, present…and future, at least the future of Coates’s son. Norman O. Brown’s Love’s Body is the “bible” of the Nobby Works after all…and at one point, Coates fairly echoes Nobby’s work when he writes,

“There is no uplifting way to say this. I have no praise anthems, nor old Negro spirituals. The spirit and soul are the body and the brain, which are destructible…that is precisely why they are so precious.”Still, I was taken aback when Coates at least twice in his book mentions what a beautiful smile he has. I didn’t see it in the framework of the body that he had constructed for his book. It struck me at first as an anachronism…from back in the day when Nina Simone did her own Love’s Body riff Ain’t Got No Life, which ends with her, lyrically at least, basking in the glow of her own smile. Nina, like many blacks of that era…especially blacks living in the public eye…and most especially black women living in the public eye...was too often reminded of how she failed to meet (how shall we call it?) failed to meet an Aryan standard of beauty. Nowadays, black faces of both genders routinely make pop lists of “best looking,” “sexiest,” “hottest.” There is no longer the stigma once attached to African facial features that required the rise of an esteem-building black is beautiful movement.

At Coates’s second reference to his beautiful smile, I sensed some insecurity about his Africanness that caused him to uncharacteristically strut his stuff in print the way he says the young bloods of his Baltimore neighborhood strutted in order to hide their fear. It’s sometimes a short stumble from esteem building to vanity tonarcissism. In Between the World and Me, Coates, unfortunately, stumbles into narcissism.

As discussed in part 2, he’s so narcissistic as to present an anonymous woman’s pushing of his son to hurry as symbolic of all the injustices suffered by the black race. The book, for all its denial of Christianity, is full of crosses it seems only Ta-Nehisi Coates has ever had to bear. Some of the crosses are lightweight. He writes about having to endure French class as if it was particularly designed to crush his curiosity (and suggesting that he never heard white boy Paul Simon sing about “all that crap he had to learn in high school”). Some of his crosses are heavyweight, the heaviest expressed in this passage where he juxtaposes the death-by-cop of his friend Prince Jones with the attack on the Twin Towers on 9/11:

But looking out upon the ruins of America, my heart was cold. I had disasters all my own. The officer who killed Prince Jones, like all the officers who regard us so warily, was the sword of the American citizenry. I would never consider any American citizen pure. I was out of sync with the city. I kept thinking about how southern Manhattan had always been Ground Zero for us. They auctioned our bodies down there, in that same devastated, and rightly named, financial district. And there was once a burial ground for the auctioned there…Bin Laden was not the first man to bring terror to that section of the city. I never forgot that. Neither should you. In the days after, I watched the ridiculous (sic) pageantry of flags, the machismo of firemen, the overwrought slogans. Damn it all. Prince Jones was dead. And hell upon those who tell us to be twice as good and shoot us no matter….I could see no difference between the officer who killed Prince Jones and the police who died, or the firefighters who died. They were not human to me. Black, white or whatever, they were the menaces of nature, they were the fire, the comet, the storm, which could--with no justification--shatter my body.As I’ve written in the past, I believe our micro experiences can help us comprehend the macro picture. In this Ta-Nehisi Coates and I seem to differ. His personal experiences overwhelm his comprehension of grand events. A woman who pushes his son becomes a stand-in for centuries of white supremacy; the first responders who died in 9/11 are echoes, shadows…alas, ghosts of the cop who killed his friend (by the way, the cop that killed Prince Jones was black and how that is both a result of white supremacy and random as a comet is an example of pretzel logic rather than the workings of a first rate intellect). Again, Coates finds human beings acting in ways many other human beings would describe as noble and brave are dismissed by him as “ridiculous.” (In an interview when asked how he feels about the families of the victims of the Charleston church mass murder forgiving the shooter, he expresses bafflement at how they could pass on their right to hate.)

Why is this? For all his book’s emphasis on the body, Ta-Nehisi Coates is not really a Love’s Body kind of guy. He seems quite fear-stricken by how easily the body can be shattered…how imminently destructible it is…and his narcissism makes him believe these are conditions unique to him and his. The philosophy of Love’s Body is that the body’s very temporary condition…its mortality…is what should provide the passion and motivation for making the most of it. Different strokes for different folks, of course. So Coates is entitled to his view, and as a parent he’s entitled…indeed expected…to pass his worldview on to his son. But before people like Jack Hamilton and Jon Stewart start telling other parents that they should be passing Coates's view on to their sons and daughters, let’s see that view for what it really is. It is not a sound accounting of how black Americans have struggled under the dominion of white Americans. There are more fully researched, better argued books to make that case. This is the memoir of a sad and uncertain man. His book opens with his reflection on a TV interview gone wrong:

At the end of the segment, the host flashed a widely shared picture of an eleven-year-old black boy tearfully hugging a white police officer. Then she asked me about hope. And I knew then that I had failed. And I remembered that I had expected to fail. And I wondered again at the indistinct sadness welling up in me. Why exactly was I sad?If I can be so bold, Coates is sad because he can’t relate to the concepts of hope, forgiveness, redemption…all those ideals that make living bearable as generations pass on from one injustice to the other…from one side of the fault line or the other. Through DNA, upbringing, or experience, these ennobling concepts have become alien to him. And he’s written a book to pass his alienation on to his son, to whom he writes:

"The birth of a better world is not ultimately up to you, though I know, each day, there are grown men and women who will tell you otherwise."And then later to his son:

“A society, almost necessarily begins every success story with the chapter that most advantages itself, and in America, these precipitating chapters are almost always rendered as the singular action of exceptional individuals. “It only takes one person to make a change,” you are often told. This is also a myth. Perhaps one person can make a change, but not the kind of change that would raise your body to equality with your countrymen.”

As I was reading Ta-Nehisi Coates in South Africa, we were engaged in business meetings in Cape Town. Most of the participants had been members of the anti-apartheid movement as young men and gone on to serve in some capacity in Nelson Mandela’s generous and forgiving majority rule government...their bodies indisputably now the equal of their countrymen. Though none of them had forgotten the indignities and injustices they had suffered under apartheid, none of them had allowed their grievances to subvert their aspirations. And for all the challenges they saw to South Africa’s future, none of them had given up on that future. It was boycotts and protests and blood sacrifice of course that had helped make it so, but it was also greatly due to the strength and hope of one mythic figure.

One of the best parts of Between the World and Me is when Coates enlists the wisdom of black sportswriter Ralph Wiley to rebuke the troubling question asked by white novelist Saul Bellow, to wit: "Who is the Tolstoy of the Zulus?" To which Wiley sagely answered, "Tolstoy is the Tolstoy of the Zulus." It's a truth that Coates seems to grasp but momentarily and then loses, it seems, by paying too much attention to cable news coverage of current tragic events. If his heart was more open, if his intellect was more curious, if his circle was wider and more inclusive he'd find that there are a great many whites in his country who answer the question: "Who is the Nelson Mandela of the white race?" by saying, "Nelson Mandela is the Nelson Mandela of the white race." More to the point, he'd find many who answer the question: "Who is the Michael Brown of the white race?" by saying, "Michael Brown is the Michael Brown of the white race."

A man with an un-proclaimed beautiful smile

A man with an un-proclaimed beautiful smile

Published on September 09, 2015 08:10

No comments have been added yet.