George Buck – B Battery XO (Executive Officer) – Part Two

Highway 19

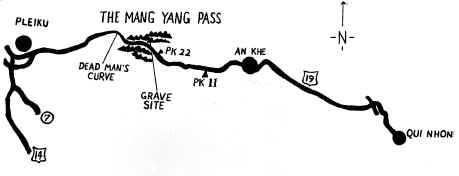

The French built Highway 19 in the early 20th century to be the main road connecting the Central Highlands with the coast. Highway 19 was a belt across the midsection of Vietnam, from Pleiku in the west to Qui Nhon on the coast. When tightened it could starve half the country. There was a saying in Vietnam: “Whoever controls Highway 19 controls the Highlands, and whoever controls the Highlands controls Vietnam.” Along its path at Mang Yang Pass in 1954, the French suffered the last and one of the bloodiest defeats of their engagement in Indochina.

My two Dusters covered a lot of territory. We traveled from near the Mang Yang Pass on Highway 19 down towards An Khe all the way up to Pleiku, then up Highway 14 to Kontum, out to a Special Forces camp near the border on an old dirt road, then to the base at Dak To. On Highway 19 near a Montagnard village is where I lost Acosta and Donovan when they drove over a land mine in my jeep.

PFC John Acosta and Specialist 4 Michael Donovan were both twenty years old when they died on January 21, 1968, just two years younger than assistant platoon leader George Buck. All three had been on their assignments for only three weeks.

Montagnard village on Highway 19 where Acosta and Donovan died

Montagnard village on Highway 19 where Acosta and Donovan died

Kill at a Distance

As assistant platoon leader – the lowest rung on the ladder for a field lieutenant – George Buck had little say in correcting the dangerous practice of riding on the dirt shoulder of a paved road. When he took over as platoon leader he was determined to make changes.

After this tragedy the platoon leader went to another assignment, and now the platoon was mine. It was an exercise in isolation. I was fifty miles from the battery commander. The battalion headquarters was down on the coast somewhere; I was never there, never ever met the battalion commander, and never saw anyone from the battalion other than the chaplain who came to our bridge site to run a memorial service for Acosta and Donovan.

I wrote letters to the families of both of our lost men, and each of the crew signed too. We got replies back from the families that helped with our sense of loss, but I swore that I would never lose another man in Vietnam, and for the rest of the year I lost no one in either Heavy Automatic Weapons or my Field Artillery assignments. Probably dumb luck but I would like to think the attention to detail on every job made a difference.

First I did not replace my jeep (a quarter ton utility vehicle). All personnel were to ride in a three quarter ton truck or preferably the two and a half ton trucks we used for hauling ammo. Every vehicle was sandbagged as much as possible, and they all carried either M-60 or 50-caliber machine guns.

I had a unique advantage in the fact I was also a Field Artillery officer, giving me the capability of fire from any artillery unit within range. Whenever possible I made contact with these artillery batteries and got preclearance from Fire Direction Control to call in artillery. Now when we got mortared I could respond with indirect fire from artillery as well as direct fire from the Dusters and Quads themselves, which was an enormous amount of firepower. (Indirect fire: heavy shells lobbed from afar. Direct fire: directly at a target.)

The mission became: Kill at a Distance, which meant don’t let the enemy get in close, go around villages if there are open fields, and don’t let anyone get close to the Dusters and Quads. This seemed to work. The platoon became much more cautious, and the only battle damage we had after that were just little bumps and bruises.

War Zone Democracy

My platoon was two Duster units, and often Quad-50 machine guns and a searchlight unit. These crews were extremely competent and only needed a mission plan to execute on their own. This was critical because they would deploy individually in the field, often at bridge sites to keep them from getting blown up at night. A Duster crew might be the only defense at that bridge and for miles on either side. It was not unusual to find them sleeping by day and working all night. Who could sleep when all you had was one Duster and a half dozen crew if you were lucky?

I maintained my platoon headquarters with one Duster at a bridge site where most of the convoy ambushes occurred. I had a second Duster crew at another bridge site closer to Pleiku where there was not as much action. I had to travel every other day or so to this other bridge site, and sometimes I would stay over. I had a problem there that was very troubling. The crew chief had a substance abuse problem of some kind. I started finding him spaced out and asleep when I would arrive. After three of these incidents within ten days, and discussions with him and the crew, I relieved him of his crew chief job. I simply told him he was being reassigned to battery headquarters.

The battery commander agreed to take him even though he did not know what he was going to do with him. At the same time he told me there were no candidates to replace him and I had to do with what I had. I said send me a fresh body and I will choose a new crew chief from the crew. I told the crew to think about who would be the best crew chief from among them. The guy had to be the best possible leader among them, nothing more. After I got the old chief on a Military Police truck and off to Pleiku the crew said they handled things and had picked a new crew chief.

He was young like all of the crew, Hispanic like most of the crew, and not someone who tried to stand out. This was my remote crew who I saw only three or four times a week. Duster crews were well oiled operations and worked best with crew chiefs who lead by example versus a strong personality. Competence was more important over charisma . This crew never missed a beat and I felt much more comfortable now that they did not have to worry about a crew chief spaced out on drugs or alcohol.

Because of the heavy casualties suffered in the heavy automatic weapons battalions they were always understaffed, and I’ll add under equipped. There were occasions where infantry and marines filled out crews. I was a prime example of someone plucked from another MOS to head a platoon. Picking a trained Duster man for a crew chief was preferable to me, and the crew knew more about itself than I did so I went with their input.

I don’t recall any training on how to handle a situation like this. Further, I was out there by myself. It is not like I had a battalion staff to help me or even the battery commander or first sergeant. The typical answer a lieutenant would get in a situation like this was simply, “Do the best you can, make it work, and don’t rock the boat too much.”

In the buildup to the American revolution the Minute Men of New England chose their own captains, who in turn selected battalion and field grade officers. Lieutenant Buck acted in that fine American tradition.

Combat Cuisine

Appetizer

We get assigned to this village and bridge site. The Ruff Puffs come out to guard the bridge and they have a dog with them. One of my guys is talking about how they are just like us: they have pets, come to our barbeques, give us bananas, and have nice villages. A shot rings out from the bridge and everyone is on the gun ready to go. Then we see poor Fido thrown on the fire. Now it is clear their pet was really their dinner.

Main Course

Two weeks after the crew chief change there is movement and noise outside the perimeter wire, which we had just reinforced as one of our security initiatives. The crew immediately opens fire with the Duster and everything goes still. The next morning what lies dead on the perimeter is an enormous water buffalo. The new crew chief calls me at my headquarters and tells me they have this problem. We weren’t supposed to shoot water buffalo, but who knew that was what it was? All they heard was noise and they opened fire. That is how you stayed alive.

I have no problem with the events, but now I have to go down there to the Montagnard village up the road and tell them what happened. We go there with the Duster so no one gets upset that they lost a water buffalo. Through sign language we tell them that they have a dead animal on the wire and please go get it. Somehow we get through to them but I have a sense they already know.

So a day goes by. Then another. This carcass on our wire blows up to the size of hot air balloon, and its legs look like little dots. Finally, after five days here comes a long line of Montagnard men with fleshing knives on long poles, like on old whaling expeditions. They carve up this rotting animal so there is nothing left but the skeleton, like what you would see in a museum.

Disgusting, but they hung it all out to dry at their village and I guess they ate it.

Dessert

On my trips between Duster sites I notice wild pigs feeding on new grasses that row up after bulldozers push the forest back from the road. The dozers do this regularly to make it tougher to ambush convoys. We have a gunner on the crew at my headquarters the guys call Country, who is a hog farmer from Missouri. Country says these wild pigs would taste good. The problem is you can’t drop them on the spot with the light round from an M16, and no one is going into the jungle to follow blood trails. You need a bigger rifle.

So back at the Headquarters bridge where the Ruff Puffs (Regional and Popular Forces) hang out I go over and speak with their lieutenant who knows English, and tell him I need an M14 or an M1 (larger cartridge weapons replaced by the M16). They have carbines (ancient French rifles) so he can’t help me right away, but if we get him something to trade he can get one. We arrange the trade for an M14 and Country becomes our pig-sniper. Within a week he makes a kill, a nice young wild pig of maybe fifty pounds.

The crew gets the pig back and hangs it from the 40 mm gun barrels and Country skins it out and starts to cut it up. Here come the Montagnards and the Ruff Puffs. One of the crew throws the hide and head into the river and before it hits the water the Montagnards and the Vietnamese are fighting over it. This is not good, typically they don’t like each other and don’t associate. So we stop the fight and declare that everyone will get something. We take the back-straps, one hindquarter and the filets for ourselves. The rest we cut up and portion out to our new friends. We use a metal drum cut in half for a barbeque pit and have a community cookout. The Montagnards give us the charcoal, which is their main industry, and the Vietnamese provide rice wine. Again I remember thinking none of this was in any of my training manuals.