Empathy and the Global Corporation

New York Times recently ran a shocking “expose” on Amazon with the ominous title “Inside Amazon: Wrestling Big Ideas in a Bruising Workplace” and the even more scary sub-heading “The company is conducting an experiment in how far it can push white-collar workers to get them to achieve its ever-expanding ambitions”. The article is worth reading. There are stories of people crying at desks, of employees seen to “practically combust” (not sure what that is, but I think I get the general drift), and then this:

A woman who had breast cancer was told that she was put on a “performance improvement plan” — Amazon code for “you’re in danger of being fired” — because “difficulties” in her “personal life” had interfered with fulfilling her work goals. Their accounts echoed others from workers who had suffered health crises and felt they had also been judged harshly instead of being given time to recover.

A former human resources executive said she was required to put a woman who had recently returned after undergoing serious surgery, and another who had just had a stillborn child, on performance improvement plans, accounts that were corroborated by a co-worker still at Amazon. “What kind of company do we want to be?” the executive recalled asking her bosses.

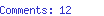

To counter this corporate PR disaster, Jeff Bezos then sent a note to his employees, where he referenced a LinkedIn post of an employee who wrote a rebuttal. While taking issue with some nominal factual inaccuracies, what the Amazon-employee says isn’t radically different from what the New York Times article tried to put forward. Ezra Klein in his excellent post on Vox explains why he thinks that’s the case [Link] (I agree) but here is my very personalized TLDR.

The Amazon employee, if you go through the note, is not really challenging the basic premise of the story. All that the man is saying, and many would agree with him, is this.

“Yeah these sissies are complaining cause they were not good enough to work in the greatest company on the world (To quote: Not everyone is qualified to work here, or will rise to the challenge. But that doesn’t mean we’re Draconian or evil. Not everyone gets into Harvard, either, or graduates from there. Same principles apply) but there are many people who are great at their work here, are motivated to work nights and weekends, and feel adequately compensated by it. Take the heat or get out of the kitchen. Booyakasha”.

Without judging the tone and tenor of his post, or sentences like “Yes. Amazon is, without question, the most innovative technology company in the world” (Psst Tesla) , I find the employee’s very alpha-male response extremely honest, as it pretty much lays out the world view of those that “win” in our present corporate environment.

James T. Kirk: Why would a Starfleet admiral ask a three-hundred-year-old frozen man for help?

Khan: Because I am better.

James T. Kirk: At what?

Khan: Everything.

Yeah. That kind.

What I am less comfortable with is what’s in Jeff Bezos’s note.

NYT article prominently features anecdotes describing shockingly callous management practices, including people being treated without empathy while enduring family tragedies and serious health problems. The article doesn’t describe the Amazon I know or the caring Amazonians I work with every day

Here is why I am not comfortable. Companies aren’t people (sorry Citizens United). People have empathy. Institutions, that exist with a profit motive, don’t. And Mr. Bezos knows this I am guessing.

Why isnt this his company? [Link]

Elmer Goris spent a year working in Amazon.com’s Lehigh Valley warehouse, where books, CDs and various other products are packed and shipped to customers who order from the world’s largest online retailer.

The 34-year-old Allentown resident, who has worked in warehouses for more than 10 years, said he quit in July because he was frustrated with the heat and demands that he work mandatory overtime. Working conditions at the warehouse got worse earlier this year, especially during summer heat waves when heat in the warehouse soared above 100 degrees, he said.

He got light-headed, he said, and his legs cramped, symptoms he never experienced in previous warehouse jobs. One hot day, Goris said, he saw a co-worker pass out at the water fountain. On other hot days, he saw paramedics bring people out of the warehouse in wheelchairs and on stretchers

And this?

Workers said they were forced to endure brutal heat inside the sprawling warehouse and were pushed to work at a pace many could not sustain. Employees were frequently reprimanded regarding their productivity and threatened with termination, workers said. The consequences of not meeting work expectations were regularly on display, as employees lost their jobs and got escorted out of the warehouse. Such sights encouraged some workers to conceal pain and push through injury lest they get fired as well, workers said.

During summer heat waves, Amazon arranged to have paramedics parked in ambulances outside, ready to treat any workers who dehydrated or suffered other forms of heat stress. Those who couldn’t quickly cool off and return to work were sent home or taken out in stretchers and wheelchairs and transported to area hospitals. And new applicants were ready to begin work at any time.

It’s easy to vilify Mr. Bezos as a heartless curmudgeon. And I am not going to. (I have an Amazon Prime membership). There is a villain here of course (all stories have them). And I am going to get there, in the time I can order something off Amazon and get it delivered to my door.

Just bear with me.

The model of corporate “benevolence” that people seem to want to hark back to is largely a romanticized ideal of the American mega- corporation in the 50s and the 60s. It was said, with some truth perhaps, that if an American worked hard and honest, he was assured of the “American way of life”, a house of his own, a car and a comfortable standard of living. Unions were strong, people still worked in manufacturing factories, and work-hours were sacrosanct. You showed up, punched in, did your work, punched out, and if your effort was honest and you didn’t steal time (or not too much), well then you were Ah-ok. Salaries were more or less even, and of course the topdogs made quite a bit though not an obscene amount more, and if that bothered you a lot, why you could go to Russia.

Then things began to change. First there was the politics. As long as the Cold War had been on, the American establishment felt obliged to show to the world and to themselves that the American working middle-class was the happiest in the world. It was one of the reasons why Communism fell, because after some time it became obvious that “capitalism” of the American kind works better for the proletariat than slave-labor-camps and communes and Politburo diktats. But once the point had been made, the American ruling class no longer really cared to keep up the pretense. Big business slowly but surely started working away at the unions, labor rights, tariff barriers and the other pesky things that get in the way of truly having fun.

Then came a new age of industrial automation through pervasive computerization and a whole lot of other manufacturing technologies that stylish tech-types would nowadays call “disruptive”. With that came that sinister word into popular lexicon.

Globalization.

The American worker found himself competing with men and women who could work hundred hour work-weeks at cents per hour, with babies strapped around their backs. Companies that still had strong unions sunk, those with weak unions renegotiated their way out. The American worker started working more for less, the forty hours became just a paper construct, and yet jobs flew away, never to return, and then Detroit happened.

Wait, you say. We know all this. I am sure you do.

But this lays the context for what Amazon and many others like them are trying to implement. The idea is not new, and it’s not rocket-science either. It’s just that the tech has finally caught up with the concept.

Let me explain.

In this world-view, you are not dealing with human beings any more. You are dealing with resources. Human beings are like…let’s say printers. You want to print out a document. There are three network printers. You see which one is not busy, you send that resource the job. There is a printer you believe is consuming too much ink. You measure printer performance, quality of print-outs, speed, with particular attention to how many pages you get out of a cartridge and the cost of cartridge. You calculate a cost per page of printing. The printer that has the highest cost per page is thrown into the dustbin, and a new printer bought. Sure you have to call in a technician to install it, and the printer costs something too, but you know that within a thousand pages (that’s what your analytics package tells you) the printer will recover that startup cost. Oh blimey. The paper keeps jamming in this printer. Junk this one too.

The challenge behind implementing this resource-driven world-view (human resource wink wink) is primarily technological. You have the problem of allocation (how do you optimize the sending of jobs to free resources) and you have the problem of measurement and decision (how do you measure which printer is “best” and how do you take decisions based on that?). It is not a coincidence that Amazon, which is primarily a retailer, has invested so much into tech. Solve these problems (or solve it better than your competitors) and you are future-proof, for a while at least.

First. Allocation.

From “Working Anything but 9 to 5: Scheduling Technology Leaves Low-Income Parents With Hours of Chaos” [Link]

Like increasing numbers of low-income mothers and fathers, Ms. Navarro is at the center of a new collision that pits sophisticated workplace technology against some fundamental requirements of parenting, with particularly harsh consequences for poor single mothers. Along with virtually every major retail and restaurant chain, Starbucks relies on software that choreographs workers in precise, intricate ballets, using sales patterns and other data to determine which of its 130,000 baristas are needed in its thousands of locations and exactly when. Big-box retailers or mall clothing chains are now capable of bringing in more hands in anticipation of a delivery truck pulling in or the weather changing, and sending workers home when real-time analyses show sales are slowing. Managers are often compensated based on the efficiency of their staffing.

Scheduling is now a powerful tool to bolster profits, allowing businesses to cut labor costs with a few keystrokes. “It’s like magic,” said Charles DeWitt, vice president for business development at Kronos, which supplies the software for Starbucks and many other chains.

Yet those advances are injecting turbulence into parents’ routines and personal relationships, undermining efforts to expand preschool access, driving some mothers out of the work force and redistributing some of the uncertainty of doing business from corporations to families, say parents, child care providers and policy experts.

Then measurement. Once upon a time, salesmen were the only ones I can think of who would continually be measured for performance. That’s because it was easy to measure their productivity. Volume of sales. Nowadays corporations are devising measures for everyone, and the lower you are in the food chain, the more you are measured. Those who have worked in call centers know what I am talking about. At retail stores, cashiers see running measures of their performance (basically how fast they are doing checkouts), and their continual employment or bonuses are dependent on staying above the average. Technology now makes it possible to continually monitor multiple sensors for data and calculate, often in real time, these metrices of performance. The companies call this instant feedback, (much of the NYT article is about Amazon’s real-time feedback system) and sometimes, just because they can be heartless, gamification.

We, of course, know what it is. The ticking timebomb on your job.

Now if you ask a captain of industry, or two, they will say that data-driven evaluations are, by definition, the most fair, removing subjectivity and bias and human error. This seems to sound kind of okay till you realize that the lower you are in the food chain, more your risk from such a metric-based evaluation system. The single mother moving the produce across the scanning machine is being judged purely on how fast her hands are moving, and how few times she has to call her manager. She has a single point of failure, herself, and so if she drops below the red-line because she has a splitting tooth-ache she can’t root-canal because she has no money to go to the dentist, she gets the pink slip. Her manager’s risk is distributed through the employees she manages, the area managers by the stores he manages. Which is why the higher you rise, the more likely you are to make your numbers, and the more likely you are to write self-congratulatory posts on Linkedin and castigate the slackers.

There is a little catch here. Since industry would like you to believe that compensation is linked purely to merit and value to company, one would have to assume the the productivity/value to company of a CEO has increased by 997% from 1978 (because salaries have) (Link) and in any year a CEO has earned, by dint of his numbers, 303 times more than the average worker. (Link).

The numbers above are worth giving a second to because it shows how the whole value-to-company “data driven” system is calibrated to benefit those at the top. It is not surprising then that the most passionate defenses of Amazon and similar companies come from the Brahmins of the company, those that get paid the most, because they have been made to believe, through the whole data-driven mumbo jumbo that they are, LO’Real style, “worth it”. The touchy-feely “we care” side of the company is exposed only to them, which is why they are genuinely gobsmacked when they hear of other employees in the same organization having radically different experiences. For instance Netflix rolled out paid maternity leave to its employees but only in its online streaming side, not the humble DVD-packers or the customer-service reps [Link]. I am sure there is some data-scientist (or a few) who earned their pay here, and a bunch of employees rolling their eyes at the complainers and moochers.

Which brings me to the point of the post. Empathy.

The modern organization, and specially the post-modern one that visionaries like Bezos dream of, do not plan for empathy. Yes empathy needs to be planned for, else it is just a nice word in a CEO note. Empathy means designing redundancy into an organization, such that the lady who has had a stillborn child is allowed a period of “low performance” because there is someone else who can pick up that work, without making that someone else burn out. That kind of planning of course almost never happens in the modern organization, especially for those at the lower end of the value scale, because the mantra is of leanness, of being pared to the bone, with no redundant cost-centers.

And if you think this is bad, you haven’t seen the future yet. The next wave of automation is round the corner, and Amazon is at the leading edge of that. Bezos will solve the Dickensian problem of workers fainting in the heat of their warehouses by replacing them with armies of robots. I have seen personally robots that implement what’s called “deep learning” and while these are research prototypes with limited functionality I have seen, the potential is truly scary. Outside the factory, Bezos will use drones for one-hour-deliveries to compete with Walmart, and you can be sure that Walmart, a company not known for its empathy, will fight back with more paring-to-the-bone, creating a hellish race for empathy rock-bottom.

For those of you engineers who are popping a beer and thinking “Haha losers”, they are going to come for you too. Remember the lucrative profession of “data entry operators”? No? Well there is a reason for that. Low-level testing jobs, the button pressing and running through scripts, are, as you read this, on the way out as sophisticated testing automaton tools become integrated into the development life-cycle. And it’s not just testing. While program-synthesis (gross oversimplification of what synthesis is: computers generating code based on a provided set of input-output sequences) has remained a pipe-dream for decades, we have now have reached the stage where the first practical implementations of program synthesis are being realized in commercial products, like Flash Fill in Excel. Which means, developers and programmers, come back in twenty years time, and tell me whether you are still a winner or part of the DVD-packing unit.

Let’s all accept this. Humans are flaky resources. They complain, break down at desks, faint during peak packing season, bad-mouth you to NYT, and get pregnant. Any dude who makes 303 times more than normal humans know that the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow is one where such flaky resources are replaced with predictable, plannable, big-data-friendly automatons.

I’ll be back.

So who is the villain here? Its not Bezos, or any of his extremely rich friends, or the Harvard MBAs who consider themselves Olympian Gods.

No it’s me. (Actually I mean you)

You see, I don’t want to deal with humans when I go to shop. I want to deal with a corporation. If I order on Amazon Prime, I expect my stuff delivered within two business days, and I couldn’t care less if you delivered your baby on the shop floor to make it happen. Tough luck, next time I will buy from Overstock. If I am at my Target checkout, the last thing I want to see is some new hire, unable to swipe a simple item and calling her supervisor for a price check, while my daughter is having a temper tantrum. If my food is cold or not done the way I want, I send it back, and I don’t care whose salary it comes from. If I want to cancel my Comcast cable account, I want to cancel it, not have to deal with an hour-long “Please stay” from an account retention executive, who is struggling to make her target and is in danger of losing her contract.

See the pattern here? I don’t have empathy when dealing with businesses and yet expect Bezos to run an organization that does.

Because no one really wants empathy, unless it’s they are talking about their own workplace. The socialist model was all about redundancy and empathy and work-life balance and more equitable pay. How has that worked? Not well.

Businesses that put employees before customers are not the people we want to buy from.

Businesses that put employees before shareholders are not the people we want to invest in.

Fun fact. People want to work for socialists but not conduct business with them. For good reason too.

They kind of suck.

And in a season where the Trump fire rages on in the US, it is doubly ironic to talk about empathy. Trump might not win in the end, but there is no doubt that his message, which can be summed as “America does not win because it has too much empathy. We need to fire some losers like I do in my show Apprentice”, is wildly popular, because many Americans, quite a few of them being the same people dubbed as “non-performing assets” by the corporations they worked for (that’s the irony part), want the same model to be applied to the country.

Because they do believe that ruthless capitalism is the best way for success.

Whether a country can be a corporation, to be run with a profit motive, is a topic for another day, but there is no doubt that of all the things that are redundant in the lean corporation of the future, there is nothing more redundant than empathy (unless it’s an euphemism for a component of a corporate benefit package to be given to that Stanford hire).

So stop hating people. And get with the game.