your second life starts when the world cracks you open

Hardships often prepare ordinary people for an extraordinary destiny. — C.S. Lewis

There’s a quote by Tom Hiddleston: “We all have two lives. The second life starts when we realize that we only have one.”

Your second life starts when the world cracks you open — usually against your will.

You learned a certain story about who you think you are and where you think you’re going. Maybe you weren’t fully conscious of what it was – we rarely are – but this story communicated itself to others through not just what you said (and didn’t say) but how you carried yourself and whom you loved (and hated) and what you wore, and what you moved toward (and crossed the street to avoid) and what you did (and didn’t do) when up against a wall.

Others reflected that story back to you, and because they were older and seemed to speak from the bones of authority, you absorbed that story more deeply into yourself, and communicated it more vividly, and others reflected it back to you…

But story truth is trickster truth. It shows itself as one thing and reveals itself as something else.

Something more.

Something that catches you – not to mention everybody else – by surprise.

If the truth of a story could be captured in words, it wouldn’t need to be a story in the first place.

Stories operate on multiple levels of knowing. That is why they engage us in ways that make us feel more alive than the actual lives we are so often living. They reach us through the senses they invoke, the emotions they take us into, the characters they leave in our memory.

Symbolism and metaphor and theme get a bad rap from high school English classes. But they are clues to the deeper life of soul, which is older than language and too complex and slippery for language to contain.

To tell you what it is, a story has to show you. Words turn to images turn to symbols: epic meaning rips through the page like the Hulk through his Bruce Banner t-shirt.

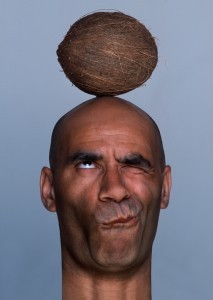

Your first life, my friend, is like a coconut.

Bear with me here.

I was walking to the farmer’s market with my eleven year old son, and for reasons that I shall leave to your imagination my son started marveling over how this thing could just fall from a tree and into the water and buoy itself along until it washes up on a beach, digs in with its slightly pointy end, roots down and grows up and out into a forest of palm trees bearing coconuts of their own.

Or else, enthused my son, some dude comes walking along the beach and says, “Oh, a coconut,” and carries it inland. He (or she) discovers that it’s food and water and dishware, all in one! Also, you can make stuff with it. Like, cool necklaces, or percussion instruments, or toys for your kids. You can use coconut timber to build houses and boats. You can make coconut oil to cook different foods. You can use coconuts to barter and trade, and develop relationships with other tribes on other islands. And no matter how many coconuts you crack open, they just keep falling and falling from the sky, no way you get them all. They keep growing, and falling, and traveling, and growing.

“What a perfect example of the selfish gene theory,” I said, taking on that professorial tone of voice that cues my son to smile and nod and drift out and in and out again.

I explained that the coconut is an excellent survival vehicle that a gene creates in partnership with other genes. These genes do not care about the coconut itself, or the joy and nourishment (not to mention the awesome accessorizing ability), it brings to people across the regions.

All a gene wants to do is replicate itself, to keep winning one of nature’s limited survival slots.

(It’s not unlike novelists competing to get on the list of a traditional publisher, with a process that is almost as brutal.)

The brilliant genes, the mastermind coconut genes, are highly specialized to perform certain functions. They team up with other masterminds that can perform other functions, and together they devise a kick-ass traveling system. The more powerful the system, the better it seeks out — or inspires other traveling systems to carry it into — the conditions needed to achieve world domination.

“Pretend that you are in a BMW,” I said to my son, “and you go up against someone in a Pinto.”

“What’s a Pinto?”

“Exactly,” I said, and felt wise.

So what if a coconut – the high-end vehicle of the plant world – serves you, but only to preserve the spark of genius that pressed pedal to metal in the first place? Is a selfish thing always a bad thing?

Life wants to live. Does it need a deeper reason?

I went to San Francisco to hear Neil Gaiman give a talk in a charming and overpacked theatre in the Castro. Neil opened with a description of trees that been on this planet for four thousand years. I can’t remember what they’re called, only that coconuts are not involved. He then recounted a dramatic story that has been in existence for as long as those trees.

The moral was this:

If you have information to send out through space and time, you must build it a story that knows how to motor.

You want people to stay away from the edge of town because there’s poison in the soil. You don’t present an academic essay. You tell about demons rising from the dirt to eat your children; and the daughter of a friend of a friend who rode her bike there on a dare and failed to return – alive and in one piece, that is.

The story grows around the unit of info like the shell of a coconut, or the gloss of your persona. We call those units memes.

The best memes win, and by best I don’t mean smartest or most factually accurate. (Some memes aren’t “true” at all: Catherine and the horse, Richard and the gerbil.) They’re in the best cars: whatever compels us to tell and retell them, pass them around, post on Twitter or Facebook or Tumblr or Instagram.

The best of the best create a sense of awe. They convey wisdom that resonates in flesh and bone.

Facts belong to surface life. The surface shifts and ripples. It goes through periodic upheavals. It reshapes into new landscapes.

We describe myths as “false on the outside, true on the inside”; we describe art as “a lie that tells the truth”; we refer to someone’s misleading statements as “emotionally true” or refer to their “reality distortion field”.

We sense, feel or imagine our way into what they’re trying to tell us, even when the words don’t align with the facts as we know them. If I describe myself as a wounded orphan when you know that I am a) in perfect health and b) so are my parents, you still ‘know’ — through the image I create in your mind — a below-the-surface truth about my childhood, my relationship to family, perhaps even the sacred wound that informs my sense of self.

Then again, I might be messing with you.

It is not ok to tell lies. We relate to each other through art partly so that we don’t have to lie, when what seems true on the surface proves false underneath.

Story truth is trickster truth.

It messes with us, but for all the right reasons.

People don’t pass around urban legends because they feel dishonest. Catherine the Great never had sex with a horse, and Richard Gere never inserted a gerbil through a cardboard tube into a place where the sun don’t shine. Sometimes the truth of the story is about the one telling it, the state of the culture and boundaries transgressed: the powerful woman who wants what she wants, the beautiful man who is wanted.

It seems fitting that the word ‘coconut’ goes back to the 15th century, originating from the word ‘coco’, which is Spanish and Portuguese for ‘grin’ or ‘monkey face’. There was something uncanny about the coconut. It was familiar enough to remind you of a head – if the head was the head of a boogeyman.

Boogeyman: a menacing version of the trickster figure who gets in your face to disrupt time and space.

He shows up to mess you up, to let you know that your coconut isn’t working anymore. Your traveling system is broken, and you must destroy it before it destroys you.

Because the purpose of your first story – the reason you co-create it with your caretakers and your culture – isn’t about truth.

It’s about survival.

It rolled you through dangerous neighborhoods, through icefields and deserts and stretches of wasteland, through mountains and forests and deepest suburbia.

You thought it was an SUV, or a Volvo, or a Mini Cooper, or a sexy Porsche, or a family camper…You see where I’m going with this. If you’re lucky, the story had some alignment with the essence of you known as psyche or soul.

But that wasn’t up to you.

The point in your life when you crack open – the why and where and how – isn’t up to you either. It happens early for some and later for others.

You move from your head to your heart.

Beneath the story you needed to live, is the other, deeper story that needs to live through you. When you’re ready (you won’t feel ready), it steps out of the shadows with love and joy — to make your life hell.

(Change is hard.)

You discover that to save yourself, you must save others.

You discover that to save others, you must save yourself.

You start to remember who you are.

From time to time you wonder at the mystery of it all. Then someone or something comes along to teach you this:

If the truth of your story could be captured in words, it wouldn’t need to be a story in the first place.

Life wants to live. Does it need a deeper reason?