Guest Contribution: “What Europeans think about Europe in the aftermath of the crisis”

Today, we’re fortunate to have a guest contribution by Jeffry Frieden, Stanfield Professor of International Peace at Harvard University, and author of the newly published book Currency Politics: The Political Economy of Exchange Rate Policy (Princeton University Press, 2015). This post is based upon this paper.

The ongoing crisis in the Eurozone has captured the world’s attention and imagination, as everyone wonders how the drama will play itself out. But the most serious crisis in the history of European integration also raises important questions for the longer run. Eventually the European economy will recover, and eventually the Eurozone will resume more or less normal operations.

Will the experience of the crisis have changed the environment within which economic policy is made? The short answer is Yes. Public opinion surveys demonstrate quite clearly that there has been a fundamental shift in attitudes toward European integration and the euro. But this shift may not be what most observers expect.

In a paper presented at a conference sponsored by the Bank of Portugal, I analyzed over ten years of Eurobarometer surveys of public opinion in the member states of the European Union, and in the member states of the Eurozone. The results paint a very clear picture of attitudes toward European integration and the euro, and of their changes over time.

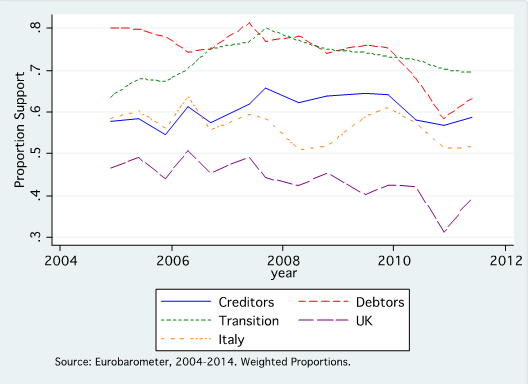

The first thing of note is that in almost every member state, with the exception of the United Kingdom and to a lesser extent Italy, European integration has been and remains quite popular. Figure 1 shows the evolution of positive answers to the question of whether the respondent thinks membership in the EU has been a benefit to his or her country, divided into country groups. Positive attitudes toward the EU have declined a bit since the crisis began, but typically 50 to 70 percent of the population thinks membership in the EU is a good thing and has benefited its country.

Figure 1: Benefit of EU membership, by region

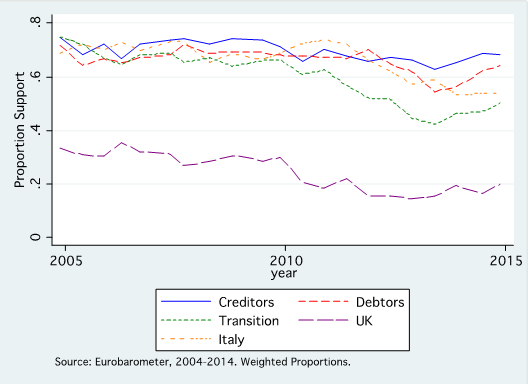

The same is true, even more so, about the euro. This is demonstrated in Figure 2. Again, among members of the Eurozone (creditors, debtors, and Italy in the figure), support for the euro is between 50 and 70 percent of the population. There has been very little erosion of support with the crisis, and in fact in some countries – such as Greece – support for membership in the Eurozone has actually risen.

Figure 2: Support for EMU

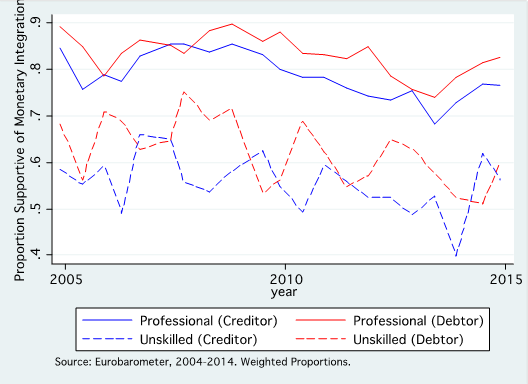

Trends at the national level obscure significant differences among socio-economic groups within countries. Indeed, there are often greater cleavages within countries than among them. Figure 3 shows patterns of support for EMU among member states of the Eurozone, differentiated between professionals and unskilled workers. As can be seen, professionals in creditor and debtor countries have virtually identical views, as do unskilled individuals in both groups of countries. On the other hand, the two socio-economic groups differ very substantially in their attitudes toward the euro, with unskilled workers about 20 percentage points less positive than professionals. There are similar differences between more highly educated Europeans and those with less education.

Figure 3: Support for EMU, groups of countries and occupational categories

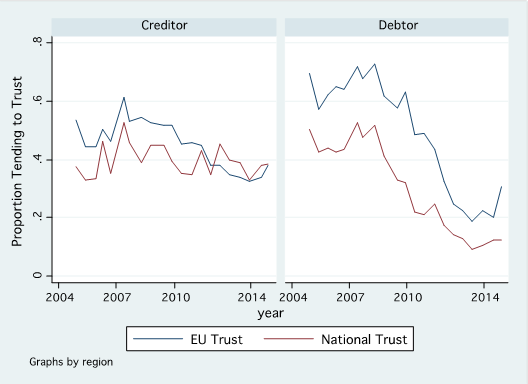

The most striking finding from a look at European public opinion, however, has to do with changes since the crisis began in 2008. The story is told graphically in Figure 4. This shows the evolution of the proportion of the population that trusts its own national government, and the institutions of the European Union, in both Eurozone creditor and debtor nations. Trends are very similar for trust in the European Central Bank among member states of the Eurozone.

Figure 4: Trust in the EU and national governments, by Eurozone country group

Since the crisis began, trust in both European and national political institutions has collapsed dramatically. In the creditor countries of Northern Europe, there has not been much erosion of trust in national governments, but trust in the EU has declined quite a bit, from a high of over 60 percent before the crisis to below 40 percent. But the real revelation is the extraordinary decline in the troubled debtor nations. National governments are seen as having failed, with trust dropping from over 50 percent to barely 10 percent. European institutions have fallen even farther, from a higher level. Before the crisis, the citizens of these peripheral Eurozone countries trusted the EU substantially more than national governments, with some 70 percent of the population having faith in the EU. By 2014, this had dropped to barely 20 percent.

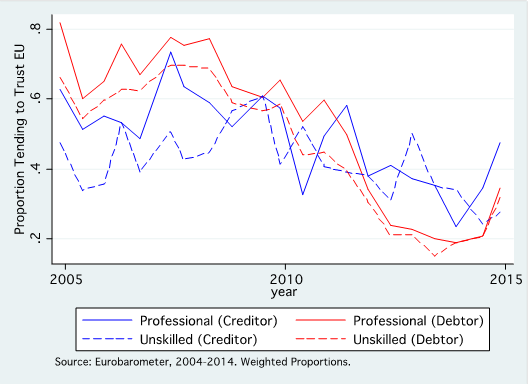

The crisis of confidence in European and national institutions is pretty much universal, especially in the debtor societies. Figure 5 shows the difference between professionals and unskilled workers. Although there is a slight gap, typically with professionals somewhat more favorable, the more important observation is the massive drop in trust among both groups in debtor societies – and a substantial decline among both groups in the creditors.

Figure 5: Trust in the EU, by country group and occupational category

Clear messages come through from the analysis of these data. They are of direct relevance to the future of the European Union, and of the euro, and they suggest a range of issues – and potential problems – that the EU and the euro will have to face going forward. I summarize them below.

Support for European integration remains high throughout the EU, and support for EMU remains high throughout the Eurozone.

There are substantial differences in the extent of this support among socio-economic groups. The differences across groups are large, and are quite similar among all member countries. Less skilled and less educated citizens are more skeptical about European integration and the euro; by contrast, the more educated and professional classes are more positive.

The differences among countries in general support for integration and the euro are not as substantial as is sometimes assumed. To be sure, non-members of the Eurozone remain unenthusiastic about EMU. But within the Eurozone, support for the euro is quite strong among all member states. And positive views of European integration more generally are quite widely shared around the Union, with the exception of in the United Kingdom.

However, the crisis has had a massive, and massively negative, impact upon attitudes toward the institutions of the European Union and of the national governments within it. Perhaps surprisingly, the crisis has not had a major effect on overall support for integration and the euro, which remains high. However, the experience of the past eight years has deeply eroded trust in the institutions of the EU and the Eurozone. Europeans, in general, still want the EU to succeed and move forward; those in the Eurozone still want the euro. But they have lost almost all confidence in the ability of European leaders and national governments to manage the problems that have arisen in the past decade.

This loss of trust in European and national institutions is particularly concentrated, as might be expected, among those who have been hardest hit by the crisis. The loss of confidence has been almost complete in the most deeply affected countries, the Eurozone debtors. Across the European Union, in general less skilled and less educated citizens, and those more likely to be unemployed, have come to hold strongly negative views about their own governments, and about the institutions of the European Union. While the data do not allow inferences about a direct relationship between this and the increasing polarization of political positions in many European countries, it is almost certainly the case that the two phenomena are related.

What are the implications of these trends for the future of European integration, and monetary union, over the coming decade? Policymakers at both the national and European level can count upon quite a deep well of support for European integration and for the euro: Europeans appear quite firmly committed to both the broad integration process and the EMU. However, they have little confidence in the ability of existing political leaders to manage both the national and European economies in ways that respond to the concerns of European citizens. This dissatisfaction is particularly concentrated in the more crisis-ridden countries, especially the debtor nations of the Eurozone. Dissatisfaction is also concentrated in those social groups that have suffered most from the crisis: the less educated and less skilled, and the unemployed.

European integration, and EMU, cannot move forward without political support from the public. At this point, such support still exists in general, but there has been such an erosion of trust in policymakers that it is hard to believe that political backing for current policies will be forthcoming for much longer unless conditions improve markedly. And, given the striking differences among socio-economic groups – and especially the great and growing skepticism of the less advantaged among Europeans – it would seem that further progress will also depend upon finding ways to include more Europeans in the gains from integration, and to shelter them from its costs.

This post written by Jeffry Frieden.

Menzie David Chinn's Blog