On Storycraft: Part 2 - Building a Story Bible.

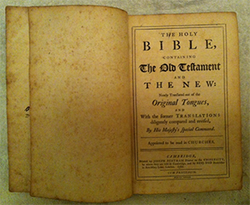

The Story Bible. The Canon of your novel, or especially a series (and, series fiction is the way to go for most fiction these days) lays down the commandments and arcana of your fictional world and should be started immediately after developing your awesome concept.

The Story Bible. The Canon of your novel, or especially a series (and, series fiction is the way to go for most fiction these days) lays down the commandments and arcana of your fictional world and should be started immediately after developing your awesome concept.There are lots of different ways to build a story bible, but my favorite is terribly disorganized and fabulously useful. If you're a stickler for proper organization in your work notes then that can be accomplished with a little elbow grease, and even give you a constant refresher on the ins and outs of your story world and the characters that populate it.

The concept has been ironed out and I'm pleased with what I have conceived. The very next step is to start a process of justification. The prime question here is: Why? Why does this story happen, why is this character at the center of it, why are the other people involved there to begin with, why are the stakes what they are? If your character, like Arthur, must assassinate a beloved senator, then you must answer the question "Why does someone want him dead in the first place?"

The universe may or may not have a divine being looking over everything with an inscrutable plan in mind, but your story absolutely does and the story bible is how you keep track of everything, justify your actions and choices in its creation. You're gong to start questioning everything: the why, who, what, when, where, and how of every aspect. Each question leads to more questions in a Socratic process of examination that will bring you a wealth of plot points and drivers, character backstory, and verisimilitude that will give credibility to your fictional world from the actions of the heroes to the monologues of your dastardly villains.

Let's keep working with the example developed in the first part of this series. "Arthur Collins didn't kill his children, but he's on death-row for their murder. When he's offered the chance at a new life, he sees the opportunity to seek vengeance and vindication for his children's death. All he has to do is kill Senator Paul Trask, a man lobbying for peace between the US and the middle east. However, when Arthur discovers a mysterious brass lamp in the Senator's home and learns of the powerful genie inside of it, he begins making wishes that not only threaten to cost him his own life, but the lives of millions of others."

There are mountains of questions to ask just from this concept blurb.

Who did kill Arthur's children if he didn't?Who offers him a chance to get off death row?Was this person or organization involved with the death of his children?Why does this agency want Arthur to kill the senator?If the senator has a genie in a bottle, has he made wishes before? What were those wishes?What were the consequences of those wishes?Where did the bottle come from in the first place? Who had it before the senator? What wishes have been made before?What wishes does Arthur make?Who else might be looking for the bottle?There's nine up front and there are many more where those came from. In answer each of these, inevitably new questions arise. I normally get out the first ten or so, answer them for myself, and then start asking questions about those answers. Sometimes, I'll give a question one or two alternative answers until I find one that I really like.

Example: First question: Who really killed Arthur's children? First answer: A man named Harvey Geissel, under the direction of a shady government organization. Why? Because of who Arthur is--not just anyone can command a genie; only people from certain bloodlines. Why? Because in the way back, it was a small cabal of Arabian sorcerers who captured and bottled the genies; only their descendants can compel a genie's power. Why did they bottle the genies? Good question...

I now have more questions! Who were the sorcerers? What kind of magic did they wield? What government organization? Why is it important to them that Arthur get his hands on the genie bottle? How did they convince Harvey Geissel to commit such an awful act of murder? Was he paid? Did he already know Arthur? What happened to him afterward?

When I enter this phase, I normally buy a new Moleskine notebook (or pull one off the stack of blank ones I collect from time to time; I buy them the way other people buy bread), label the front of it for the book/series, and then start asking and answering questions in its pages with a pen or pencil. You might prefer an e-Document of some sort. Recently I was playing around with scrivener links. One file has a list of questions, and the answers are spread out in individual files with answers; those answers are linked back to the questions so that a searchable index begins to develop. You can cross-link keywords as well; maybe you mention a particular character or setting in an answer, and want to link to information about that element - just make a new document file for it, highlight the keyword, and link it to the appropriate doc. (If you haven't already you need to be learning how to utilize scrivener, it is a marvelous tool for writers.) (Come to think of it, I may write a blog post about a bunch of nifty things you can do with scrivener.)

Ahem. As you answer questions you can organize them if you like into separate files or segments for characters, settings, foreshadowing, interior myths (that is, mythical elements interior to the story world), and so on. I like to peruse my growing story bible and mine for new questions and veins that offer richer material for scenes, shocking reveals, and so on.

The story bible is also where you'll establish the rules of the world. What kinds of wishes can our genie grant? How many does it grant? Is there any limit at all (of course there is, there should always be limits on magic or you won't end up with much conflict)? Where do genies come from? What other things exist, if they exist, and do they factor into the story at all? Are genies the only magic in the world? What is the nature of magic in this story? Is it limited, like oil, or a force, like gravity?

The purpose of the story bible is to give you a solid foundation that you can refer to as you build the plot, as well as get your creativity bubbling and boiling with ideas for where the story might go. Mine normally has snippets of dialogue, some creative description, ideas for later books if it's a series, and so on. All of this happens before the outline, but by the time I've got a little pocket note-book full of story errata, I have a much more complete sense of the story. It's beginning to come alive. Of course the whole bible isn't finished yet--that is a process that can potentially go on forever. It's world-building, myth-making, and story-prepping.

Exercise Time!

Take a good long look at your concept. Pick out at least two questions to start with about the main character, his circumstances, the event, and the consequences or stakes that your character is promised to face. It'll give you eight questions to start with. Answer these questions after you've written down all eight, and then begin the process of digging even deeper. If you hit a dead end, go back a few questions and start on another branch.

Published on May 12, 2015 19:46

No comments have been added yet.