Understanding children, special needs or not. The Miracle Worker in the Library Project

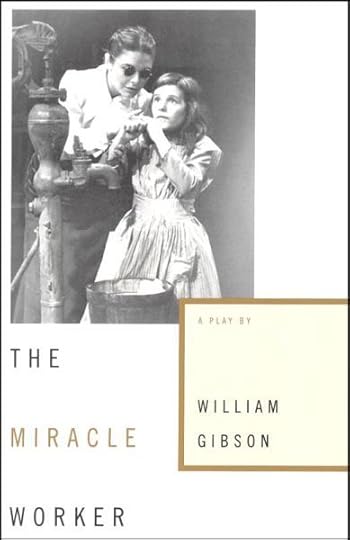

Title: The Miracle Worker: A Play

Author: William Gibson

File Under: Plays, Foundational, Child Development, Read-Aloud (and perform!), Education, Special Needs, Homeschooling

Age Group: From adolescence to old age

A work of art can convey truths in a way that no textbook ever can. If that art is based on, as they say, “a true story,” it can be even more compelling. The insight we gain is irreplaceable.

Yet, I would say that in our day-to-day life, especially when it comes to child-raising, we increasingly base our principles on textbooks, not on art or experience or even common sense. Textbooks (and studies, and scientific literature based on studies, and posts shared on Facebook) carry an air of authority, but often we forget to ask about the ontology of the conclusions presented.

In other words, we accept the findings of the experts, but we don’t inquire into their world view. What do they have in mind when they advise us on how to treat our children, difficult or otherwise? What do they know about what it means to be a human being — about human nature?

What are their goals? What is the picture they have in mind when they speak of “normal” or “appropriate” or “acceptable” or even just “possible” behavior?

What expectations do they have for the parents? What resources do they think that the parents have? Do they take into account their limitations?

Yes, my observation is that the experts view parents as very limited, but in a self-defeating way. They think that parents are hopelessly lacking in insight into their own children (which can often be true! But not fatally so!). But they utterly prescind from the question of virtue — of whether the parents have any, are seeking any, or even know that it matters.

When I was very young I read The Miracle Worker, saw the play, and watched the movie. And the story formed my attitudes about child-raising in general, although it’s about the blind, deaf, and mute Helen Keller, whom Annie Sullivan, a difficult and strong-willed young woman, rescues from a terrible fate — a life of being treated as less than human.

As you read, try to forget what you know about the important figure Keller was to become, and consider the point of view of the other family members. She was truly spoiled, as a result of the combination of her willful temperament, which was to stand her in good stead when channeled, and her family’s combined indulgence and dislike. She had seemingly overwhelming physical limitations. She was dirty (as mentioned in the play!). How hopeless it all seemed.

This short play presents in dramatic form much wisdom about the human condition, not least of which is that a person must have suffered in order to be of use to someone else who is suffering. Annie can help Helen because she has struggled with her own shortcomings — physical and moral — and the struggle has made her virtuous and wise, well beyond her years. Helen’s family cannot help her because they don’t struggle, not even against their helplessness, although they do pity and they do worry.

Literature, as so many before me have observed, offers us vicarious growth. (Thank goodness, as there is no way that any one person can undergo all the experiences necessary for acquiring all the virtues! Yet completely virtuous we must strive to be!)

So we ourselves undergo a moral transformation as we are offered in turn all the choices we can make, through the various characters in the play. As they do, we can feel paralyzed by our shortcomings and our uncertainty; we can merely pity; we can impatiently dismiss; we can have contempt.

We can do the worst thing of all, which is succumb to a kind of acedia: the apathy of not wishing to exert the energy necessary to turn to the good and change accordingly. Parents do often lose hope this way. We fail to act on what we know is good for our child.

The crux of the matter — as it is in the play — is reality.

Annie Sullivan must overcome the household’s despair to connect Helen with reality, against huge odds. But pay close attention as you read: The greatest obstacles she faces are not Helen’s physical handicaps. No, the obstacles are the other people, and that in their diverse weaknesses, no one has had the wisdom and courage to treat Helen as if they exist.

They have not given Helen any what we here at our house like to call reality feedback.

Don’t fail to notice that among other things, they think she’s too young!

Annie expresses this in terms of manners after her first encounter with Helen. Pay close attention to how manners connect with the very thing that restores Helen to her own humanity: finding meaning her connection with the world.

This lesson is one which every mother and father must internalize in order to do a good job raising children, because the whole task can be summed up as introducing the child, hopefully gradually and with firmness and affection, to the reality of the world outside them and the self-control to deal with it.

If we don’t embrace this task — including with the “special needs” child — we often find that we have consigned them to facing the task alone, later, with abruptness and often entailing what seems like cruelty from others (as when Annie isolates Helen from the family and their false pity).

Indeed, a whole category of literature deals with this very situation: that having been cheated of the curriculum of self-control in the school of virtue that the healthy family offers, the child must endure a painful rehabilitation at a later point.

I’d say most of us fall into this category! Which is why reading or watching this play can be so cathartic for us. It was for me!

What the story teaches us is that each child is unique and incomparable, with a spirit all his own, however buried under whatever we might characterize as handicaps; and that the whole adventure requires our own moral growth.

So you can see why having children is so good for us, assuming that we don’t settle for merely managing their behavior.

Which, alas, I fear is the tacit goal of many experts.

Had it not been for Annie and her virtue of fortitude, the world would have not received the gift of the extraordinary humanity of Helen Keller, with all her flaws and all her energy. And we would not have received the gift of a compelling lesson in overcoming our shortcomings for the sake of our children, because we would have no idea that this is the way to proceed.

So this is why I’m calling this book “foundational” — a book that you might spend time reading now, so that later you’ve internalized its message. Thus, this play is an excellent choice for your 6th to 8th grader who is a good reader but too young for the classics. What a study of human weaknesses and strengths!