No Relation (III & IV)

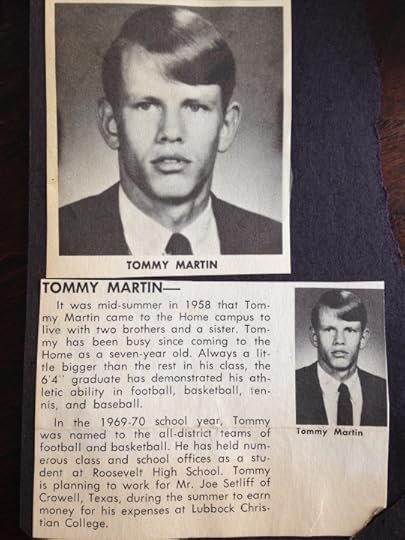

In the lead up to father’s day, I’ll be serially posting this essay on relation and the coincident, which is also a meditation on my father and Robert Creeley. The following is the last two sections, but the third section’s incomplete, so this is a working draft. (Need to treat Hawkins’ Back to Texas more directly, & would welcome interlocutors, if anyone would like to comment/read.) Pictured above: my father’s graduation announcement from the Lubbock children’s home.

III.

“The poem is a capsule where we wrap up our punishable secrets.”—The Autobiography of William Carlos Williams, p. 343

In “Inside Out,” Creeley frames Williams’ oft-cited claim about “punishable secrets” (from a passage, it bears noting, on visits with Pound at St. Elizabeths) as a Puritanical approach to autobiography. Creeley notes the “clear signs of a kind of paranoia in this mode, just that the I feels itself surrounded by a they to which its experience of itself cannot easily refer” (CE 562). Creeley’s punishable secret: that, at the time, he shared this paranoia. (Maybe not so secret, certainly not the only thing punishable.)

The formulation always strikes me as a lie or a seduction—an effort to sex up the work of doing poetry—so it’s funny that Creeley calls it Puritan (funny, too, because if WCW and RC were standing side by side, I’d likely point that finger at the latter, if forced to choose). More to the point, to write a poem and to call it work, to tuck away some sin and then hustle to sell it off to a readership, would seem to require a pretty deep well of weirdness to maintain the public interest, if that’s your model—but the truth is that so many truly punishable secrets aren’t, at least in the absence of a high public profile, so readily forgiven, even in poetry. A good hustler includes the juicy bits, but not the real transgressions.

Alternate take: Kyle phones to say Creeley was writing mileage and maintenance logs—who did what & where they did it, etc. I like it, but the more I sit with it, I start to think it’s too metaphoric, still—like the horse poetics. Most types of what I’ll call real work you can’t apply for a money prize to afford you time to do the work in the first place.

“Inside Out” was completed in Buffalo on March 22, 1973—my father’s twenty-first (false) birthday. He only found out late in life that he’d actually been born the day before. He’d taken a job hot-shotting (hauling small loads, not large freight exactly), which led to an offer to drive truck for 7-11 on a promotional tour to the east coast, passing out free t-shirts and Slurpees at special events or whatever. The drive would take him, presumably, across the border into Canada, so he’d have to get a passport, and the passport folks told him they’d need his birth certificate, which he’d never had. When he went to get it, he discovered he’d been celebrating the wrong birthday all his life, and as a consequence, had to get his license changed, too.

I’m not sure whether it was that the people who ran the children’s home relied on the kids to fill out the paperwork (who were very close to right, if that’s what happened), or whether they simply couldn’t keep the birthdays straight among the 20 or so kids who lived with each family. Either way, the news really wrecked my dad—one more joke at his expense, from beyond the grave. But he loved the trip so much he brought us all free 7-11 shirts. A friend of my mom’s wore hers to the funeral.

“I figure the most evident problem with this separation, or what to call it, will be boredom, and the restlessness that comes of it,” Creeley writes to Bobbie Louise Hawkins from Buffalo, January ’73, after a kind of nostalgic road trip across country. He’d just moved back to New York again: Hawkins had initially remained in Bolinas, and Creeley made a point to drive through New Mexico, down memory lane as it were, passing through Albuquerque and environs where they’d lived in the ‘50’s and ‘60’s, to get to Buffalo.

The letter’s longish, about settling in, unpacking, etc.—about the trip there, pollution, the weather (taking the temperature re this time apart):

Apparently local Buffalo paper had pictures of Bolinas’ flooding, house falling down hill (?)—sounds like a wild time. I hope that creek kept the waters moving off our so-called property. Albuquerque, by the way, now has smog all through the valley […] The whole city felt jumped into ultimate Princess Jean Park vision of ‘success’—later saw “The Brave Cowboy” on late-night TV, appropriately enough. Texas was COLD … panhandle frozen stiff, but in garage where I went to get push for frozen car by that point (morning), lovely conversations going on with ‘good ole boys’ and ‘waal’ and what you’d expect. Last thoughts of Albuquerque: local Buffalo radio/tv report of commissions’ recommendation that LA would have to cut down on gasoline consumption […] —reaction is, apparently, to lower the standards qualifying smog […] Too fucking much. Like the farmer’s horse living on less and less till one day he just died. What a weird imagination of success!

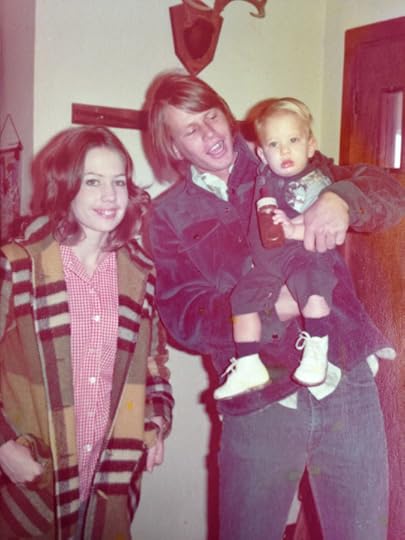

Shortly after Creeley’s trek through the panhandle, my parents met for the first time at an apartment complex in Odessa. There are two stories about how:

One version has it (and this one I grew up with) that my great grandmother, wife of a Baptist preacher, warned my mother off of the skeezy looking guy with the long hair while helping her move into her new apartment complex, and that later my dad showed up at my mom’s door in a towel to borrow soap or something. In this one, dad’s a bad seed, which fits with some of what I know about them both at that age: she frequented a rock club called The Shadows, and he was a roughneck, for one. He had a fiery temper, liked to cut loose by hustling pool, drinking, and fighting; one of his best friends was named Tom Goodnight (a super sweet biker who once let us pick up beer cans from his property for a school recycling fundraiser—mountains of cans, like an alcoholic junkyard). Dad has a black eye in my parents’ wedding photos from a bar fight the night before.

The other version I only learned recently, during my mother’s recovery from the injuries she sustained in the tornado, which resembled, one rad-tech said, a biker who slams head-on into a brick wall. A couple of weeks after the storm, my mother told a very different version to Julia of how she and my dad met, and then told me. In this one, she was out on a date. The guy driving took what she thought was a wrong turn, and when she said so, he told her that they’d go wherever it was only after she put out, that otherwise she’d be walking home. She chose to walk, a few miles or something (luckily it was really an option), and when she got there she realized she’d left her purse in the guy’s car and didn’t have her keys. So, she knocked on the door of the apartment where my dad and my uncle Gary lived and asked if she could use the phone. Only after calling whomever for her spare did she register that she’d just traded one threat for another, but she waited with them, got to talking, and she and dad hit it off. My understanding is she never told my dad exactly what brought her to his doorstep.

IV: Two Codas

“Hold on, dear house […] You are my mind / made particular” — from “This House” (Echoes)

When my parents moved Julia and me to Buffalo in the summer of ’05, my dad and I fought like we hadn’t done since my teens. He was pissed; I was impatient. There’s no room for his F-250 on the one side of Linwood Ave. that allows parking. And the parkable side of our new block changes depending on the day of the week or something, so this became a big issue for him—proof I’d chosen against him I think (moving across country for a Ph.D., settling in a ‘big city’). I maybe had, but I didn’t think that’s what I’d been doing.

Once I’d asked if he wanted me to bring anything back for him from the east coast. His response was casual, but compulsively forthright: “I never lost nothing in New York.”

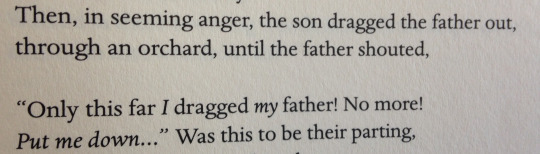

And now I think of Creeley’s repurposed folk tale of the impudent son who attempts to kick his father off his land (was never sure whether he got it from Stein or elsewhere, who uses it to open The Making of Americans):

(“For Will,” from If I Were Writing This)

Stein adds that “It is hard living down the tempers we are born with.”

… And I think maybe that’s what I’d done after all, dragged him across country to drag him out, period—my house as my mind made particular.

Whereas my dad aged out of a children’s home and moved to Odessa to be closer to the father who’d left him there. Upon arrival in 1970, he went to work on a rig for my uncle James. I remember James by his metallic green Cadillac, my Aunt Barb’s gold-sequined cigarette case. He has dementia now*, but just before the tornado he and my dad met again after I don’t know how many years. When they spoke of the oil field, James was completely lucid.

Julia and I stayed in Buffalo for less than a year before I quit Ph.D. work, then back to Texas.

Journal entry, 2-28-14

First birthday without my father is a different kind of birth. A renewed grief when I woke up that I couldn’t pin down until my mother called to wish me happy birthday & it dawned on me that it was now a half wish, a clipped conversation in the absence of his voice chiming in.

A birth to grief a few months shy of his one-year death day. I try to remember his voice, to put the words in his mouth (in my head) & best I can do is an association: at the end of Johnny Cash’s “Oney” the spoken part always reminds me of my dad, of something he’d say, so in lieu of imagining him wishing me a happy birthday, because I can’t get the sound of his voice around those words in my mind, I listen to him laugh and repeat: “Hey Oney! Own-ie!” The lyrics are the employee’s threat whose first act upon retiring is to find his boss (Oney) and beat the shit out of him. I hear him laugh and repeat the threat, letting his pitch climb on the last “Own-”—even see him kind of cock his head, a little amused at the song, at the threat.

1/8/14-3/18/15

* James died in July 2014, while I was drafting this essay.

C.J. Martin's Blog

- C.J. Martin's profile

- 11 followers