Wandering through Waterloo, pt 2

The Lion's Mound at Waterloo with the Rotunda to the left

By ADRIAN TAHOURDIN

Anyone who feels Waterlooed out need read no further. Suffice to say that although the French are alleged to be avoiding the subject altogether, Le Monde today contains a special eight-page supplement, culminating in an interview with Napoleon���s most recent biographer Andrew Roberts, who believes Waterloo need never have been fought ��� ���Napoleon was no longer a threat to peace���. Roberts���s French rival biographer Patrice Gueniffey, meanwhile, writes in Le Figaro that Napoleon���s defeat marked the true end of the French Revolution. ���Waterloo was the first day of the nineteenth century, just as August 1 1914 was the first day of the twentieth century.���

With the anniversary in mind, I thought it would be fun to look again at Stendhal���s great novel The Charterhouse of Parma: early on in the book, Stendhal sends his picaresque hero the seventeen-year-old Fabrice/Fabrizio del Dongo, from Como in northern Italy to Paris, on a heroic quest: ���He had gone with the firm intention of meeting the Emperor [during the Hundred Days]. It never occurred to him that this might be difficult . . . . In Paris, every morning he went to the courtyard of the Tuileries palace to watch Napoleon taking the salute at the march-past; but he never managed to get close to the Emperor��� (my translation). Fabrice finds his way to Waterloo, attaches himself to a regiment and a sympathetic corporal takes him under his wing. He even acquires a horse, which he is promptly relieved of. Caught up in the French retreat, he witnesses the following exchange between the corporal and a wounded general:

���You���re to give me four men,��� he said to the corporal in an exhausted voice, ���to carry me to the ambulance. I���ve got a shattered leg.���

Go f*** yourself,��� replied the corporal, ���you and all the generals. You���ve all betrayed the Emperor today.���

As Fabrice spends two weeks recovering from a battle wound in an inn at Amiens, he wonders whether what he saw was really a battle and, if so, was it Waterloo? Stendhal���s brilliant depiction of the battle is generally reckoned to be accurate in its detail.

Walter Scott was the first ���celebrity��� to visit the battlefield (although people had begun arriving from Brussels the following day to survey the carnage). Having heard news of Wellington���s victory in Edinburgh on June 24, Scott set off with three friends the following month, taking in the fortress of Bergen-op-Zoom and the sights of Brussels on the way (where he noted with satisfaction the good impression the regiments of the Highland corps had made on the citizens). It was his first foreign trip and he followed it with an extended stay in Paris. The resulting, commissioned, account, Paul���s Letters to His Kinsfolk, which is full of fascinating detail, was published in January 1816. (I reviewed a new edition, Scott on Waterloo (Vintage) and which includes Scott���s epically dreadful poem ���The Field of Waterloo��� and an excellent introduction and notes by Paul O���Keeffe, in last week���s In Brief pages of the TLS).

Robert Kershaw���s 24 Hours at Waterloo (WH Allen) is an excellent compendium of ���Voices from the battlefield���, complete with timelines and maps, which makes for absorbing if grim reading. Kershaw, a former Para turned military historian, writes that ���even by the ghastly standards of the day, Waterloo was universally regarded as being extremely violent���. He has a nicely caustic tone: ���British soldiers shared Wellington���s somewhat jaundiced opinion of ���foreigners���. Soldiers, as they do, swiftly reduced them to stereotypes: brave but nervous Frenchmen, brave but clumsy Prussians, cowardly Belgians, inexperienced Dutchmen and of course brave, stoic and courageous Englishmen���.

Kershaw���s use of first-hand accounts brings the day to life: ������A storm, such as I had never seen the like of, suddenly unleashed itself on us and on the whole region���, wrote Lieutenant Jacques Martin, 45th Line Regiment, part of the leading French corps.��� Ensign Edmund Wheatley of the King���s German Legion wrote that ���a ball whizzed up in the air���; ���up we started simultaneously���. ���Glancing at his watch he saw ���it was just eleven o���clock, Sunday morning���. His sweetheart Eliza Brookes . . . would be ���just in church at Wallingford or at Abingdon������.

And the French made an impression on the enemy: Corporal John Dickson of the Scots Greys wrote ���The grandest sight was a regiment of cuirassiers dashing at full gallop over the brow of the hill opposite me, with the sun shining on their steel breastplates. It was a splendid show. Every now and then the sun lit up the whole country. No one who saw it could ever forget it���.

Kershaw tells us that, up to Waterloo, Napoleon had won all but ten of his seventy-two engagements, but they had taken their toll. ���Physically, Wellington was more vibrant than the increasingly flabby Napoleon��� (a temporary exhibition back at the Waterloo museum on the two leaders��� crossed destinies reminds us that they were both forty-six at the time, born within three months of each other in 1769). Soldiers of the Grande Arm��e noticed how much weight the Emperor had put on since his enforced stay on Elba.

Other nuggets include the fact that ���boots in 1815 were a single issue; there was no such thing as a right or left foot���; that local coalmines made muddy, storm-sodden conditions even worse (���Coal dust coated the local roads and produced a ���black mud mixed like ink������, according to Captain Duthilt, a veteran of the Revolutionary Wars); and that Marshal Ney, the ���Red Lion��� of the French troops, who was ���fighting combat stress after the failed Russian campaign���, saw five horses killed under him that day.

And recent excavation in preparation for the building of a car park, Kershaw writes, ���unearthed a complete skeleton���. ���This soldier may well be one of the many thousands of Wellington���s ���Infamous Army���, unknown and uncelebrated���.

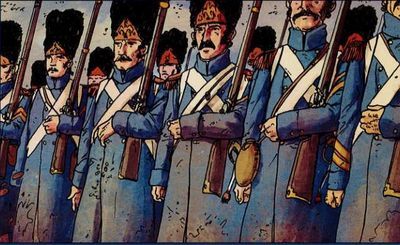

Waterloo being in Belgium, the country of Herg�� and Tintin, there is a new bande dessin��e account of the battle (below), published by Sandawe. Paris-Match, meanwhile, last week had a thirty-two-page special supplement on Waterloo (the French really aren���t entirely avoiding the subject).

For those who don���t really believe that Napoleon died on St Helena in 1821, I can recommend the short novel The Death of Napoleon (1986) by the late Simon Leys, translated from the French by the author and Patricia Clancy and reissued in a new edition by New York Review Books. It���s a gem.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers