A Key to Relatable Characters

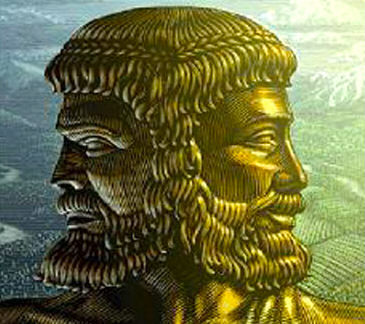

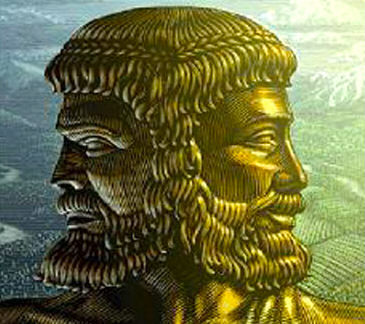

When a character displays traits that make them hypocritical, deceitful, treacherous, we might even say evil, we use the term “two-faced”. Interestingly, the expression “two-faced” is based on a greek deity Janus (from which we get the name for the month of January), who was known for having two faces, one which peered forward, one which peered backward.

Every character, then, ought to be “two-faced”. Only by understanding where a character has been can we understand where the character is going. In other words, rather than boldly attempting to make our personal story a battle of good and evil, make it a story of opposed intentions and motivations. In this way, your audience will be drawn in by characters they truly understand. Who knows, they may even pick a hero to despise or a villain to cheer for, but they will enjoy the story.

We need to understand here that a villain need not always be nefarious, nor a hero be a constant force for good. A wide subsection of fiction is based on antiheroes. The effort taken to craft an antihero is actually the same effort that should be used to develop all heroes and villains. Consider: an antihero is someone who has genuine motives behind his actions. We can generally relate to an antihero more easily than a villain or hero. Han Solo speaks to a wider audience than Yoda or Emperor Palpatine. Tony Stark, in spite of his wealth, is a more relatable character to most than Captain America or Ultron. Why is this? The human race is filled with flawed people, most of which have good intentions.

Let’s rephrase that statement more simply: The actions of people are based on motivations and intentions. (Good and heroic, or bad and villainous, motivations and intentions are the key.) Let’s then, compare two words: Intention and Motivation.

Intention: An Aim or Plan. (Looking ahead.)

Motivation: The reason for acting and behaving a specific way. (Looking back.)

Every character should have clear intentions and clear motivations.

Mysteries are based on the study of motivation. The protagonist–in this case, the detective–intends to discern a motive from the antagonist–the criminal–and works toward this aim in a variety of ways. Once the motive is established, he can give the motive a face, an identity.

When we develop a story, we decide on the protagonist and the antagonist. But if we really contemplate these roles, they represent characters who are opposed to one another. But (here’s where the matter gets interesting) the protagonist need not be a hero, nor is the antagonist required to be a villain. These are simply characters whose objectives are opposed. Really, the best villain is one whose motivations lead him in a course opposed to the hero, not simply someone doing evil for evil’s sake. And, that being said, the villain may display traits that may be heroic and altruistic, but for the opposing side. If your villain is, by all attributes, someone to cheer for, your audience won’t know what to expect, but they’ll stick with you every step of the way until they find out.

Now, because I firmly believe that authors have the responsibility to teach and learn from one another, to build the best stories possible, I invite you to share your thoughts on the following questions: how do motivations and intentions lead to more profound characters? How can writers better demonstrate deeply motivated characters? Which sorts of conflict have arisen from this in your personal storytelling projects?

About the author: Iffix Y Santaph is the author of the YA science-fantasy series Forgotten Princess. It is his intention to build a world full of well-rounded, deeply motivated characters. The first book of this series Impulse is available now from a variety of online retailers, including Amazon.com.

newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

I've been experimenting a lot with the villain as a hero lately, and plan to do so to greater effect in book 5 of my series.

I've been experimenting a lot with the villain as a hero lately, and plan to do so to greater effect in book 5 of my series.

Iffix wrote: "I've been experimenting a lot with the villain as a hero lately, and plan to do so to greater effect in book 5 of my series."

Iffix wrote: "I've been experimenting a lot with the villain as a hero lately, and plan to do so to greater effect in book 5 of my series."

So whether every character should have clear intentions and clear motivations is in one sense, questionable. They should seem clear, but that’s not the quite the same thing. If a character doesn’t know what they want -- despite thinking they do -- these questions get complex, and that complexity may be the whole point of the narrative. Learning what you really want is a key component of personal growth. And characters that don’t grow tend not to be as interesting.

As to how to better demonstrate this, that’s tricky. In 1st person, the author has the advantage of writing from the character’s perspective, which is revealing, but a harder time show other character’s perspective, which are a useful clue as to what is going on (actions speak louder than words). There are also the dangers of inner monologues that drag out and lose the reader. Dialog can be used, but that has risks too: it’s easy to make such conversation stilted.

In the end, I think it comes down to observation. When you’re in a group of people, you get a sense of them and how they’re feeling, and to what extent their actions and statements agree with or are in conflict with their thoughts and feelings. How exactly do we derive these impressions? What are the precise clues? Being sensitive to that and being able to convey it realistically will carry conviction to the reader, because readers notice the same things, even they aren’t fully conscious of it.

I especially liked this: “If your villain is, by all attributes, someone to cheer for, your audience won’t know what to expect, but they’ll stick with you every step of the way until they find out.” That is quite true, and we have used it to good effect. In our last book, the “bad guy” was also one of the characters that seemed to have more strongly engaged our readers sympathies. I could be mistaken, but I think that engages readers more fully than a simple struggle between “good and evil”.