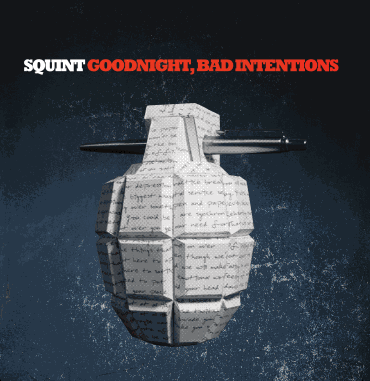

Welcome to the Break My Heart Show: A review of squint's "Goodnight, Bad Intentions"

A lot has happened for squint (lower-casing intentional) in the five years since the release of t Tinsel Life, their second studio album. They've toured extensively, they've lost a few members and gained some new ones. They've released a music video and are already at work on two more. They've been robbed, endorsed (Jagermeister, Atlas mic stands), and have, as of something like a week ago, become the opening credit band for a Canadian television show.

For most of us—at least those of us would spend time on a site like, well, this one—this might be enough excitement to hold us over a couple decades. For squint, however, this is all just par for the course. The members of the Austin- based quintet thrive on choas, and as their latest album Goodnight, Bad Intentions demonstrates, they have grown from all this hard work, honing their songwriting skills and stengthening their group dynamic.

based quintet thrive on choas, and as their latest album Goodnight, Bad Intentions demonstrates, they have grown from all this hard work, honing their songwriting skills and stengthening their group dynamic.

The album is raucous and energetic, loaded with catchy hooks and the kind of self-deprecating wit that has made them staples of college and indie radio stations across the nation (they were recently ranked number 3 on the Reverb Nation Charts for Austin, where they also performed an acoustic set at SXSW festival). Alternating between frenetically-paced numbers like "Flustered" and slower, more moderate tracks like "To My Protagonists:" and "Elisabeth," GNBI showcases the band's versatility and lyrical dexterity in a way that their previous albums have hinted at but never fully disclosed. The guitars take on a much more prominent role here; this, presumably, has a lot to do with the addition of guitarist Ronald Norman who, along with primary guitarist Matt Fredrickson, provides a kind of second vocal presence that nicely offsets that of lead vocalist Dane Adrian.

It's probably a stretch to say that the band's music has grown angrier over the years, though they do seem to have cultivated a healthy degree of cynicism. For instance, it's probably no coincidence that the first track on the album, "We All Break the Same," opens with the lines, You must have/mistaken/me for a sympathetic ear, nor does it seem to be by chance alone that this song segues wonderfully into the scathing "To My Protagonists:," : This is a song/for all the people/who asked me to write about them/you ain't worth an entire song/but I got all these little lines/and you  can figure out which one is about you.

can figure out which one is about you.

What makes songs like these so gut-punchingly resonant is their steadfast sincerity: there's never point in "Protagonists," for example, at which the listener doubts that there really are people who've demanded some kind of musical head-nod from the band, and that Adrian really does view the band's music as a kind of weapon. In fact, that's precisely how he characterizes it in the following verse: "Always/I am armed with ballpoint pen/and memories/careful with your tone my friends." (Adrian, by the way, might have one of the most interesting voices in indie rock right now; imagine Johnny Rotten channeling the dude from Filter.)

By this measure, it's impossible not to think of GNBI as anything other than a kind of musical memoir, culled from a scattering of bitter journal entries. Take, for instance, the first few lines of "Elisabeth": I'm guess I'm in denial/isn't that the first stage?/I'm searching for a meaning/but nothing comes to mind/I'm really looking forward to depression/cos that means that I am one step closer/to accepting that constant reminder of change/that something is different than it was just a moment ago. Who looks forward to depression? Well, if the success of indie-pop is any indication, pretty much all of us. That's a large part of why we listen to music in the first place.

Fans of the band will no doubt be familiar with the song "Tinsel Life" off the album of the same name, in which Adrian, portraying a character in the throes of heartbreak, narrates his frantic search through his CD catalogue for a tune that that may properly epitomize the situation. What's interesting about the track is that, in a kind of too-obvious-to-even-notice way, this seems perfectly reasonable. Why shouldn't finding the most appropriate song be the primary concern when one's heart is breaking? Of course every breakup demands a soundtrack. This is the way that we (or at least those of us in that certain bracket of folks who appreciate good indie rock) make sense of our failures, those low points when our expository abilities become irrelevant, troublesome. That is sort of why we have bands like squint, to remind us during those times that all the melodrama, all the sophomoric stuff that sends us scurrying to our CD racks, actually does have meaning, that with the right soundtrack, it's not so bad.

when one's heart is breaking? Of course every breakup demands a soundtrack. This is the way that we (or at least those of us in that certain bracket of folks who appreciate good indie rock) make sense of our failures, those low points when our expository abilities become irrelevant, troublesome. That is sort of why we have bands like squint, to remind us during those times that all the melodrama, all the sophomoric stuff that sends us scurrying to our CD racks, actually does have meaning, that with the right soundtrack, it's not so bad.