when you're strange

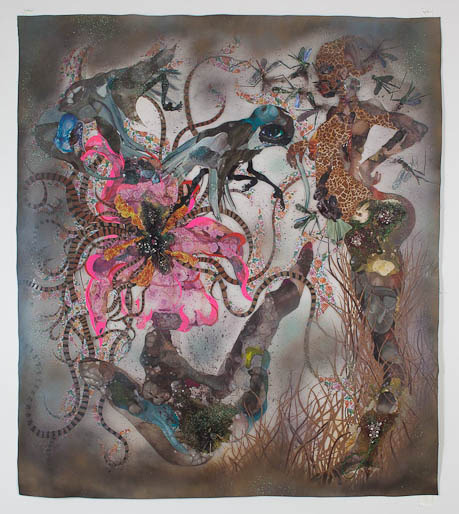

I don't often go into Manhattan, but ever since Sandra Payne mentioned on Facebook that there was a new exhibit by Wangechi Mutu, I knew I needed to check it out. I first saw Mutu's work at the Brooklyn Museum—I think one of her pieces was included in the 2007 "Global Feminisms" exhibit. Yesterday might not have been the best day for me to look at art; I've got a new novel percolating in my brain, and I just started reading Hiromi Goto's Half World. Add hormones to the mix and I probably should have stayed at home! But it was the last day of the exhibit ("Hunt, Bury, Flee") at the Barbara Gladstone Gallery, and I saw on Facebook that Wangechi Mutu would be giving a talk at 2pm. Nicole, who blogs at The Hotness, organized and announced the talk but when I called the gallery that morning to confirm the time, I was told the talk "might not be open to the public." The gallery would be open while the talk was conducted, however, so I was encouraged to come by and listen in. Turns out Nicole had something different in mind—a very open, informal conversation with Mutu followed by a video screening and refreshments upstairs. Unfortunately, I didn't make it to the end. After half an hour of perusing the dozen or so works of art on my own, my head was already full of words that needed to be written down; then a certain personality started to dominate the discussion and so I moved to the edge of the group and then left after about an hour. I don't have the best social skills; I'm used to hitting MUTE on my remote when someone's speech annoys me or I simply surf to another channel. But group dynamics are tricky and if I'm not the professor at the head of the classroom, then I'm part of the captive audience. I should have stayed, but have enough to say about the two pieces Mutu discussed. We started with Humming, pictured above, and Nicole read aloud a list of words that Mutu associates with her work; one was a Swahili term for a process of utilitarian recycling of discarded items. Mutu pointed out that in developing countries, recycling isn't a matter of dealing with (the guilt of) excess; rather it's a necessary project whereby poor people render useful those things which others have thrown away. Old tires are turned into sandals, for example, and I thought of El Anatsui's use of wooden market platters and discarded bottle caps. Mutu talked about how children use wire and aluminum cans to make toys, and I thought of my boys doing just that in "Muñecas." Then she explained how this informs her own creative process, even leading her to reshape pornographic images of black women's bodies. I asked how she understood the term "organic" but didn't properly explain my intent; it's ironic that I'm drawn to black feminist art because I'm a black feminist, and yet was concerned about taking up too much space in that moment (some men in the group didn't have that problem). In the US, "organic" signifies a kind of purity—and privilege. Organic fruits and vegetables are more expensive, and yet look less appealing sometimes—less robust and imperfect because they aren't "protected and preserved" by chemicals. When I talk about wanting my writing to be organic, I think about an absence of interference—no external editor telling me to do this or change that. For Mutu, "organic" means allowing creation to unfold naturally; since having a child, she's learned not to force or try to control things. I imagine collage takes a great deal of patience, especially when working against perfection and symmetry. Mutu's pieces are absolutely fascinating; her women are distortions, their bodies fragmented, broken yet repaired or forced to cohere by adhesions—mechanical bits, parts of motorcycles or other machines, the hides of wild animals. Mutu inserts symbols of delicate beauty—butterflies,

I don't often go into Manhattan, but ever since Sandra Payne mentioned on Facebook that there was a new exhibit by Wangechi Mutu, I knew I needed to check it out. I first saw Mutu's work at the Brooklyn Museum—I think one of her pieces was included in the 2007 "Global Feminisms" exhibit. Yesterday might not have been the best day for me to look at art; I've got a new novel percolating in my brain, and I just started reading Hiromi Goto's Half World. Add hormones to the mix and I probably should have stayed at home! But it was the last day of the exhibit ("Hunt, Bury, Flee") at the Barbara Gladstone Gallery, and I saw on Facebook that Wangechi Mutu would be giving a talk at 2pm. Nicole, who blogs at The Hotness, organized and announced the talk but when I called the gallery that morning to confirm the time, I was told the talk "might not be open to the public." The gallery would be open while the talk was conducted, however, so I was encouraged to come by and listen in. Turns out Nicole had something different in mind—a very open, informal conversation with Mutu followed by a video screening and refreshments upstairs. Unfortunately, I didn't make it to the end. After half an hour of perusing the dozen or so works of art on my own, my head was already full of words that needed to be written down; then a certain personality started to dominate the discussion and so I moved to the edge of the group and then left after about an hour. I don't have the best social skills; I'm used to hitting MUTE on my remote when someone's speech annoys me or I simply surf to another channel. But group dynamics are tricky and if I'm not the professor at the head of the classroom, then I'm part of the captive audience. I should have stayed, but have enough to say about the two pieces Mutu discussed. We started with Humming, pictured above, and Nicole read aloud a list of words that Mutu associates with her work; one was a Swahili term for a process of utilitarian recycling of discarded items. Mutu pointed out that in developing countries, recycling isn't a matter of dealing with (the guilt of) excess; rather it's a necessary project whereby poor people render useful those things which others have thrown away. Old tires are turned into sandals, for example, and I thought of El Anatsui's use of wooden market platters and discarded bottle caps. Mutu talked about how children use wire and aluminum cans to make toys, and I thought of my boys doing just that in "Muñecas." Then she explained how this informs her own creative process, even leading her to reshape pornographic images of black women's bodies. I asked how she understood the term "organic" but didn't properly explain my intent; it's ironic that I'm drawn to black feminist art because I'm a black feminist, and yet was concerned about taking up too much space in that moment (some men in the group didn't have that problem). In the US, "organic" signifies a kind of purity—and privilege. Organic fruits and vegetables are more expensive, and yet look less appealing sometimes—less robust and imperfect because they aren't "protected and preserved" by chemicals. When I talk about wanting my writing to be organic, I think about an absence of interference—no external editor telling me to do this or change that. For Mutu, "organic" means allowing creation to unfold naturally; since having a child, she's learned not to force or try to control things. I imagine collage takes a great deal of patience, especially when working against perfection and symmetry. Mutu's pieces are absolutely fascinating; her women are distortions, their bodies fragmented, broken yet repaired or forced to cohere by adhesions—mechanical bits, parts of motorcycles or other machines, the hides of wild animals. Mutu inserts symbols of delicate beauty—butterflies,  dragonflies, hummingbirds—into scenes that hint of environmental disaster. One black woman seems to dissolve into an oily mass reminiscent of the recent BP spill in the Gulf. Dragonflies have long black legs and so become mosquito-like and menacing; between a woman's splayed legs we find pearls buried in soil, and from the soil sprouts dry weed-like strands (Sprout, at right). I immediately thought of the saying, "Never cast pearls before swine," and then I thought of my own little art project and how hard I work to keep things even and pristine. It takes courage and daring to mix materials the way Mutu does—is she redeeming black female sexuality by representing the body in this organic way? After seeing endless airbrushed images of the black female body, this does seem closer to "the truth." While she was discussing Humming, this white man walked through the group and planted himself right in front of the image (!!!). Then turned and walked away….I don't particularly want HIS gaze on these images, though it was interesting to hear Mutu say that in majority-black countries (she's Kenyan) the dictators are black and the poor people are black, too; race isn't what distinguishes one person from another. I like that her work implicates other blacks in the

dragonflies, hummingbirds—into scenes that hint of environmental disaster. One black woman seems to dissolve into an oily mass reminiscent of the recent BP spill in the Gulf. Dragonflies have long black legs and so become mosquito-like and menacing; between a woman's splayed legs we find pearls buried in soil, and from the soil sprouts dry weed-like strands (Sprout, at right). I immediately thought of the saying, "Never cast pearls before swine," and then I thought of my own little art project and how hard I work to keep things even and pristine. It takes courage and daring to mix materials the way Mutu does—is she redeeming black female sexuality by representing the body in this organic way? After seeing endless airbrushed images of the black female body, this does seem closer to "the truth." While she was discussing Humming, this white man walked through the group and planted himself right in front of the image (!!!). Then turned and walked away….I don't particularly want HIS gaze on these images, though it was interesting to hear Mutu say that in majority-black countries (she's Kenyan) the dictators are black and the poor people are black, too; race isn't what distinguishes one person from another. I like that her work implicates other blacks in the  violation and exploitation of black women. The next piece we discussed, I Sit, You Stand, They Crawl, made me think of another post I saw on Facebook recently that featured a quote by US Secretary of State, Madeleine Albright: "There's a special place in hell for women who don't help other women." That's essentialist thinking, of course, though I often subscribe to it myself. I do expect more of other women and am more disappointed when they fail to come through. I was watching To the Contrary yesterday morning and the women panelists were discussing a new report that shows women *mentor* other women but don't seem to *sponsor* them. In other words, "I'll show you the ropes, but I'm not helping you climb this ladder." What does that say about women in the workplace? They're too busy, too overwhelmed by their responsibilities to promote other women? Or do they simply suffer from that human flaw that makes dominance pleasurable, the ability to control another's movements and/or block her progress: "I may not be able to break through this glass ceiling, but I'm sure as hell going to sit on top of all these other bi***es." I just had that conversation with a writer friend who finds one particular elder only recommends mediocre young professionals so that his status remains unchallenged. Ugly! Organic? Is this who we are when we strip back the facade of politeness—that fake niceness women so often perform? Ok, I could go on but I'd better get back to this new novel. If you get the chance to see Mutu's work, take it! She's got exhibits all over the world…

violation and exploitation of black women. The next piece we discussed, I Sit, You Stand, They Crawl, made me think of another post I saw on Facebook recently that featured a quote by US Secretary of State, Madeleine Albright: "There's a special place in hell for women who don't help other women." That's essentialist thinking, of course, though I often subscribe to it myself. I do expect more of other women and am more disappointed when they fail to come through. I was watching To the Contrary yesterday morning and the women panelists were discussing a new report that shows women *mentor* other women but don't seem to *sponsor* them. In other words, "I'll show you the ropes, but I'm not helping you climb this ladder." What does that say about women in the workplace? They're too busy, too overwhelmed by their responsibilities to promote other women? Or do they simply suffer from that human flaw that makes dominance pleasurable, the ability to control another's movements and/or block her progress: "I may not be able to break through this glass ceiling, but I'm sure as hell going to sit on top of all these other bi***es." I just had that conversation with a writer friend who finds one particular elder only recommends mediocre young professionals so that his status remains unchallenged. Ugly! Organic? Is this who we are when we strip back the facade of politeness—that fake niceness women so often perform? Ok, I could go on but I'd better get back to this new novel. If you get the chance to see Mutu's work, take it! She's got exhibits all over the world…