Conflating culture with doctrine: a potential follow-up to ‘Confessions’

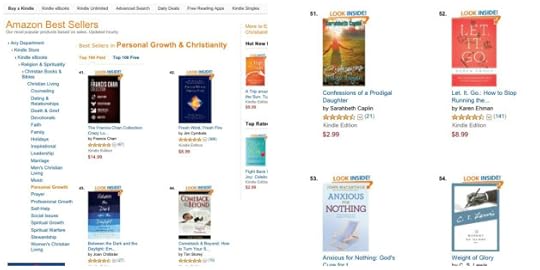

I’m tinkering with the idea of a follow-up to Confessions of a Prodigal Daughter, which scored spot #64 on Amazon’s top 100 free Kindle books and #51 in paid ‘personal growth’ books this week – right next to C.S. Lewis.

In fact I already have a working title in mind: Add Jesus and Stir: a Jewish-born Christian’s attempt to understand Christian Culture. We’ll just see where it goes…

***

I’m sitting on the floor of Isabel’s living room, munching on frosted cookies and sipping lemonade, thinking that the dainty yellow plates and flowered napkins are an odd juxtaposition against the heavy subject matter: Isabel’s beloved grandfather just passed away.

I’m sitting on the floor of Isabel’s living room, munching on frosted cookies and sipping lemonade, thinking that the dainty yellow plates and flowered napkins are an odd juxtaposition against the heavy subject matter: Isabel’s beloved grandfather just passed away.

The sad news created a thick atmosphere in the room, since no one knew what to say. No one ever really knows what to say when there’s a death – until Isabel gives a sigh of relief that despite the awful disease he suffered, at least he was now in heaven. In fact, he accepted Jesus as his savior just a few years back, before his diagnosis. The mood of our meeting completely changed as the women rejoiced and praised God: at least he got saved before it was too late.

I am the only one who is silent. For my father, according to traditional Christian doctrine, there is no such relief. There would be no such praise. I cannot hold on to the hope the other women had about the eternal fates of their loved ones, since mine are all Jewish.

And it occurs to me, for about the millionth time since I started seminary, that Jews would never say such things. Announce a death in a room of Jews and you’ll likely hear, How awful. That’s tragic. I am so sorry. Can I bring you a meal? There would be no concern for where the loved one’s soul is residing, and no one would think to ask.

“Let’s pray before we begin,” announces Colleen, who chose the reading for this week. We all bow our heads: “Dear Heavenly Father,” she begins, “We are saddened by the loss of Isabel’s grandfather, but we praise you so much for reaching his heart before he died. Use his life to remind us all to share the gospel with everyone you have placed in our lives.”

I couldn’t help thinking, Jews don’t say this. A Jew would never say this. If this Bible study were a Jewish one (which, I suppose, would be more aptly called a Torah study), the language would be completely different. I’d find those prayers more straightforward, unlike Christian prayer, which is often riddled with expressions like “Use my life,” “Touch his heart,” “Guide me through your Word,” and other sentiments that, quite honestly, I understand without actually understanding. I know that “touch his heart” isn’t literally asking to feel the organ in the crevice of one’s chest (that would just be creepy), but to inspire, to encourage, to comfort. I’ve thought to myself, Why not just say that, then? Why all the vague imagery? None of it felt right on my Semitic tongue. I was learning lines, but was not a good enough performer to convince an audience that I knew my part.

I thought to myself, This may be my religion, but these are not my people. How can that be? What is religion without a community to go with it? It’s not because we don’t all believe the same things (more or less), but like the Tower of Babel, our speech has gotten confused. I cannot effectively communicate with this group if their language is not my mother tongue.

Then again, the women of this Bible study and most Christians in general would find it just as strange to learn words like kvetching, chutzpah, schlepping, and putzing. To me, those are all integral parts of my vocabulary, and might always be. If I cannot call myself a Jew by faith, I can join the ranks of most of America’s Jews and consider myself a Jew by culture.

Culture. It’s such an interesting part of every major religion: churches and buildings of worship still, for the most part, abide by the teachings of ancient holy texts, but the surrounding culture is unique to each generation of followers. Fifty years ago, worship bands did not use fog machines and flashing lights. It was not expected or even normal to find a full bookstore and coffee shop next to the sanctuary. Youtube videos with catchy, self-deprecating titles such as “Stuff Christians Say” did not exist, as the “stuff Christians say” was still being developed. Much of that is the mark of a “hipster” generation trying to keep faith relevant in a high-tech, modern age.

And that’s not a bad thing. The problem is when culture is conflated with the doctrine itself, and when people like me who don’t care much for worship music and feel uncomfortable praying out loud in front of others are made to question if they are even Christian at all.

There are other sticky parts of adopting a faith in adulthood, when it’s not something you took for granted as a child: uncomfortable and even disturbing teachings about sin and hell. That is not culture; that’s the faith. But even depictions of the afterlife through art, books, and film have weaved through culture over the last two millennia, which can and does alter our perception of what is Truth – what the biblical authors intended for us to imagine when they wrote with inspired hands.

Filed under: Religion, Writing & Publishing Tagged: Author Sarahbeth Caplin, cancer, Christian culture, Christianity, Confessions of a Prodigal Daughter, evangelicals, grief, hell, Indie Author Life, Judaism, Writing