On a scale of Anne Frank to ISIS: thoughts on grace and inherent worth

I’ve heard varying explanations regarding humanity’s true worth and value. Some Christians believe we all have inherent worth and value because we are made in God’s image, a mindset that fits well with the Jewish one I was taught. But there are other Christians who believe it is only when you accept Christ’s sacrifice that you gain (not earn!) worthiness. I’ve consulted many a dictionary to parse the difference between “unworthy” and “worthless,” and have loosely concluded that they are not the same thing when used in a spiritual context. We are sinners, therefore unworthy of heaven, but worthy enough for Jesus to die for us.

That being said, I have a hard time swallowing the idea that not being worthy of heaven means we all deserve hell. Eternal punishment for finite crimes – I’m still working through my beliefs about that, or what I think hell even is. Not all Christians believe it’s a literal lake of fire, but eternal separation from God – whatever that means. The definition of “good person” has as many explanations as there are people. One culture’s “good” is another culture’s evil: the members of ISIS probably think they are candidates for Muslim sainthood; most everyone I know views their actions as the epitome of evil. If “good” can be measured on a scale of Anne Frank to ISIS, do most of us slide more towards Anne? What about people somewhere in the middle? At which point on the spectrum does one become an official “bad” person?

I think it was easier for me to see myself as a lowly sinner in need of redemption because of what my boyfriend did. The rapes were bad enough, but I was also forced to walk several paces behind him if we went out in public, so people wouldn’t assume we were a couple. He’d walk so fast my little legs could barely keep up, and he would become irate if I asked him to slow down. When he eventually found someone else, and actually changed his relationship status on Facebook to acknowledge it – something he never did with me – it solidified the fact that something was obviously wrong with me. There had to be, or else I never would have been kept a secret.

I needed therapy, certainly, but more than ever I was convinced I needed Jesus to redeem me. I was literally nothing; I needed Jesus to become something, because the narrative of his life spoke to my desperate need for significance and worth. I am not shy about admitting that the reasons for my conversion were primarily emotional ones: I think they are for most adult converts, trying to make meaning out of something awful. I never pored over the Old Testament prophecies to see they really pointed to Jesus – I needed a promise of tangible redemption that Judaism didn’t have, or wasn’t ever taught to me. Jesus fit that need perfectly. Unlike my abusive relationship, it was okay, even encouraged, to make my identity all about him.

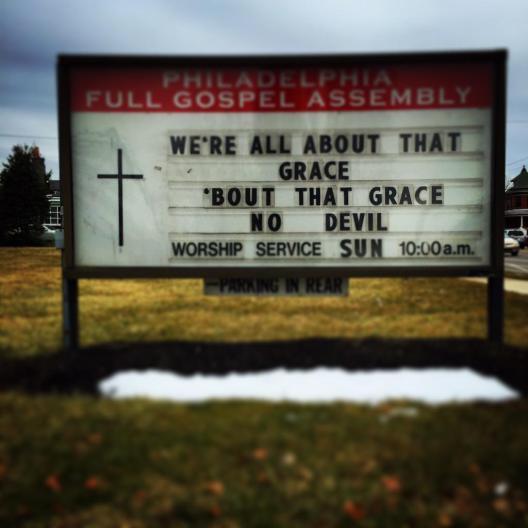

Nowhere is this point driven harder than during the worship portion of an evangelical church service. The depth of our common depravity and general helplessness is frequently set to heart-rendering, somber, or at times even catchy tunes: sticky little earworms that are so easy to learn and whose melodies you catch yourself humming while doing dishes or sitting in traffic. So catchy are these songs that you might not stop and critically consider what it is you’re singing about; I certainly didn’t.

In my college ministry days when I thought the sincerity of your faith was measured by how loud and passionately you sang, I waxed poetic about my despicable attempts at righteousness and the wickedness of my heart without so much as a “Wait, what?” I still wonder, and I’ll never really know for sure, how much I would have gone along with this if not for that abusive boyfriend who convinced me of my worthlessness long before the Gospel did.

Because she was one of my first role models, I can’t help but wonder sometimes what Anne Frank might think of all this. There’s no way of knowing how much she knew about Christianity, but if she were able to attend a mainline Protestant church service today, the girl who once wrote “In spite of everything, I still believe that people are good at heart” might be appropriately horrified. After what my boyfriend did, I couldn’t disagree with her more – but isn’t it arguable that what the Nazis did to her and her family was far worse? If she could still believe in inherent goodness in spite of what she went through, what’s holding me back?

“The world,” as Christians say, referencing anyone not following the narrow path of salvation, would come to two radically different conclusions about such a conviction: Anne is either a Jewish saint, or just plain crazy.

Frankly, whenever I read the newspaper or hear stories about ISIS’ latest crime against humanity, it’s not hard to believe we’re all inherently wicked, or at least capable of becoming so. And it goes without saying that if my boyfriend, my first love, acted manipulative and heartless from the very beginning, I never would have returned his calls. Such is the unfortunate trend of abusive relationships, for anyone wondering why so many women put up with them: they never start out that way. By the time you realize you’re in over your head and possibly in grave danger, you’re either too dependent (financially or otherwise) or too desperate to believe that that kind person still lives inside, and this violent monster isn’t who he really is.

In my case, I wanted to believe the latter; not only because I was in love, but as a way of saving face. It’s humiliating when your friends and your family figure out the truth before you do.

But just because one man I thought was good – he was a devout Catholic, believe it or not – turned out to be the opposite doesn’t mean everyone is like that (cue the #NotAllMen protests). Most people have the ability to act decent, if not outright pleasant. But we all know that some people are better at acting like it than others.

If it turns out that most humans are basically okay and don’t really need the gospel – what would we need to be saved from, otherwise? – I know the depth of my depravity. I know that I need grace for the times I thought awful things about the woman buying hotdogs with food stamps; the obese couple at the all-you-can-eat buffet; the classmate who brags about the number of men she’s slept with and wears skirts that barely cover what should be covered in public. I know I do these things; many times I feel justified in doing so. When I sing about needing a savior, I am singing for myself.

Similar sentiments and more in Confessions of a Prodigal Daughter, ranked #51 in Amazon’s top 100 ‘personal growth’ memoirs.

Filed under: Rape Culture, Religion, Writing & Publishing Tagged: Author Sarahbeth Caplin, Campus Crusade for Christ, Christian culture, Christianity, Confessions of a Prodigal Daughter, Controversy, depression, evangelicals, Facebook, grief, hell, Writing