Pan and Scan

Okay, it's a leap, but talking about Pan Books in the Sam Peffer post reminded me of something that's all but disappeared with the advent of widescreen TVs; the 'panning and scanning' of movie prints for TV broadcast.

We've reached the point where the 4x3 Academy Ratio TV set is only ever seen as a prop in period dramas, but for over fifty years it was the standard. All programming was made in that almost-square format; anything that wasn't had to be fiddled to fit.

In the early days of widescreen cinema, studios saw TV as the enemy. Going bigger, wider, and more spectacular was the response, and it's said that some would even go out of their way to ensure that their images would play badly on the small screen. It was a shortsighted view; TV was to extend the earning potential of any feature way beyond its original release window.

Regular readers of the blog will know that one of my earliest jobs was in the Presentation Department of a commercial TV company. On the rare occasions when we broadcast a print in full widescreen with 'black bars' above and below the image (aka 'letterboxing'), the Duty Officer's phone would ring off the hook with viewers' complaints. Even when our Telecine engineers attempted a compromise, zooming slightly to lose the edges of the image and minimise the letterboxing, viewers were unhappy. It was like they wanted their screens completely filled up with picture on principle.

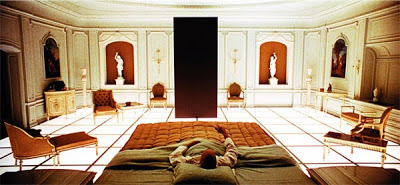

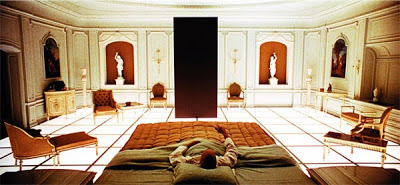

Letterboxing of films was rare on ITV. You'd find it more often on BBC2 or Channel 4, in the arthouse slots. Mostly we'd be provided by distributors with special TV prints of studio features, already adjusted for the shape of the screen by the process known as panning and scanning. The prints came with every scene reframed and optimised for TV. This involved losing anything up to one-third of the picture detail, along with all original sense of composition.

Panning and scanning could go way beyond the cranking of a frame to the left or right to squeeze the action in - a small section of a scene could be selected and enlarged to make a closeup from a medium shot, for example. I recall a scene which, in the original, was a single long take of two people talking. The telecine operator had reframed each person in a separate, enlarged closeup and then cut back and forth between them, playing editor. Didn't match, didn't work, looked appalling. But it used to be quite common.

Those calls of complaint seemed to persuade my bosses that no one out there really cared about quality. Or at least that they only cared for a Philistine's version of it - fill up my screen, crank up the colour until every face is orange, and nothing in Black & White, thanks very much. It was an assumption that persisted well into the Home Entertainment revolution, despite the fact that the revolution was driven - as all revolutions are - by a desire for something better. One of the great annoyances of being an early adopter of widescreen TV was that of finding that the DVD you'd just paid top dollar for had been mastered from one of those 4x3 television prints.

(Ipcress File, I'm looking at you. A crappy Carlton release which I've since upgraded to Network DVD's superior issue.)

Now all TVs are 16x9 and while that ratio doesn't correspond exactly to any theatrical format, it lends itself to less noticeable compromises. When I began shooting my own stuff the viewfinder on the film camera included an element with the 'safety zones' of the different viewing formats etched into the glass, so that the operator could ensure that whatever the composition, the essential information would fall within the frame and the shot would always make some kind of sense. Now such information's more commonly found on the video assist monitor. If you see a movie where you can make out the edges of the sets, or the microphone dips into shot, then it's probably not being shown in the ratio for which the operator framed it.

In Presentation now, everything's been turned on its head. It's old ('vintage') 4x3 material that causes the negative audience reaction. People shy away from 4x3 the way they shy away from Black & White.

In this case the choice is between seeing vertical black bars to either side of the image (pillarboxing) or zooming to fill the frame, losing the top and bottom of the picture and, once again, bolloxing the composition. The results are just as ugly as Pan and Scan - uglier, if anything, with exaggerated grain, noise, and visual clutter in images that were low-resolution to begin with.

Then there are those directors who shoot a digital frame, then add letterboxing to mimic a Panavision effect on a 16x9 screen.

To which one can only say, Dream on.

We've reached the point where the 4x3 Academy Ratio TV set is only ever seen as a prop in period dramas, but for over fifty years it was the standard. All programming was made in that almost-square format; anything that wasn't had to be fiddled to fit.

In the early days of widescreen cinema, studios saw TV as the enemy. Going bigger, wider, and more spectacular was the response, and it's said that some would even go out of their way to ensure that their images would play badly on the small screen. It was a shortsighted view; TV was to extend the earning potential of any feature way beyond its original release window.

Regular readers of the blog will know that one of my earliest jobs was in the Presentation Department of a commercial TV company. On the rare occasions when we broadcast a print in full widescreen with 'black bars' above and below the image (aka 'letterboxing'), the Duty Officer's phone would ring off the hook with viewers' complaints. Even when our Telecine engineers attempted a compromise, zooming slightly to lose the edges of the image and minimise the letterboxing, viewers were unhappy. It was like they wanted their screens completely filled up with picture on principle.

Letterboxing of films was rare on ITV. You'd find it more often on BBC2 or Channel 4, in the arthouse slots. Mostly we'd be provided by distributors with special TV prints of studio features, already adjusted for the shape of the screen by the process known as panning and scanning. The prints came with every scene reframed and optimised for TV. This involved losing anything up to one-third of the picture detail, along with all original sense of composition.

Panning and scanning could go way beyond the cranking of a frame to the left or right to squeeze the action in - a small section of a scene could be selected and enlarged to make a closeup from a medium shot, for example. I recall a scene which, in the original, was a single long take of two people talking. The telecine operator had reframed each person in a separate, enlarged closeup and then cut back and forth between them, playing editor. Didn't match, didn't work, looked appalling. But it used to be quite common.

Those calls of complaint seemed to persuade my bosses that no one out there really cared about quality. Or at least that they only cared for a Philistine's version of it - fill up my screen, crank up the colour until every face is orange, and nothing in Black & White, thanks very much. It was an assumption that persisted well into the Home Entertainment revolution, despite the fact that the revolution was driven - as all revolutions are - by a desire for something better. One of the great annoyances of being an early adopter of widescreen TV was that of finding that the DVD you'd just paid top dollar for had been mastered from one of those 4x3 television prints.

(Ipcress File, I'm looking at you. A crappy Carlton release which I've since upgraded to Network DVD's superior issue.)

Now all TVs are 16x9 and while that ratio doesn't correspond exactly to any theatrical format, it lends itself to less noticeable compromises. When I began shooting my own stuff the viewfinder on the film camera included an element with the 'safety zones' of the different viewing formats etched into the glass, so that the operator could ensure that whatever the composition, the essential information would fall within the frame and the shot would always make some kind of sense. Now such information's more commonly found on the video assist monitor. If you see a movie where you can make out the edges of the sets, or the microphone dips into shot, then it's probably not being shown in the ratio for which the operator framed it.

In Presentation now, everything's been turned on its head. It's old ('vintage') 4x3 material that causes the negative audience reaction. People shy away from 4x3 the way they shy away from Black & White.

In this case the choice is between seeing vertical black bars to either side of the image (pillarboxing) or zooming to fill the frame, losing the top and bottom of the picture and, once again, bolloxing the composition. The results are just as ugly as Pan and Scan - uglier, if anything, with exaggerated grain, noise, and visual clutter in images that were low-resolution to begin with.

Then there are those directors who shoot a digital frame, then add letterboxing to mimic a Panavision effect on a 16x9 screen.

To which one can only say, Dream on.

Published on May 14, 2015 03:30

No comments have been added yet.