The Voodoo of Elevation Gain and Strava (and How I Get Around It)

Note: this article may not appear properly in news readers.

This article contains interactive aspects that are likely removed by most news readers. Please see this particular article directly on Jeffrey's blog for full functionality.

A Light Mountain Climb After Lunch

340m climb from the village of Kurodani, Takashima City, Shiga Japan

高島市黒谷からの山登り

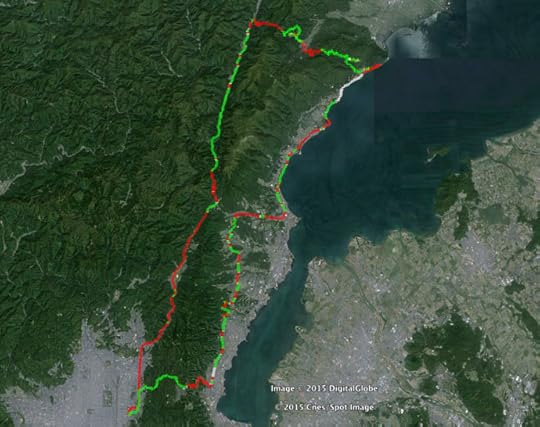

In the screenshot of Google Earth above, you can see the route that I rode my

bicycle last Wednesday... the little bit of green coming in from

the right is a downhill section of road, followed by the long red uphill section

through the tiered rice paddies of the village,

then up the mountain on an old road no longer open to traffic.

I'd ridden 55km (34mi) to get to that point, and would end up riding

72km (44mi) farther before I got home, but ever

since my first “real” ride in

February, I've not been so interested in how much distance I've covered,

but rather, in how much mountain I've conquered. This means the important

statistic for me is how much “vertical

climb” or “elevation gain”

I did during a ride,

the sum of all the rises/climbs/ascents on the route.

And it's not just me... vertical climb is often used as a badge of

achievement for a ride, and seems to get more talk than distance. It's a strong reflection for how tough a route is.

The problem is that it's difficult to figure out the vertical climb for

a particular route, and commonly-used methods are often wildly

inaccurate.

Cyclers I've met record the ride with a GPS unit of some sort

(their iPhone, a bike computer, a runner's watch, etc.) and upload the

data to Strava, a service that allows

you to analyze your activity and share info about it with others. It's very popular and mostly very well done.

For example, I mentioned it in my previous post about a long mountain bikeride

that I did on April 30th, where Strava had informed me that I had beaten my

record for a particularly tough mountain climb:

Data About My Rides

Courtesy of Strava.com

Footnote: I've since beat it again, but by only 10 seconds.

When you upload your data to Strava, they calculate your vertical climb

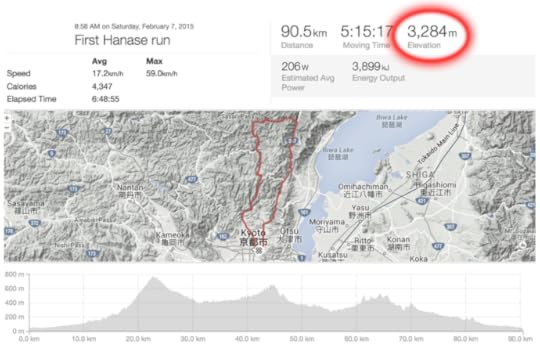

for the activity, and display it prominently. For example, the

aforementioned first real

mountain ride shows some impressive stats:

Since it was my first real ride, I didn't know any better but to be

impressed by the 3.3 kilometers (2 miles!) of vertical climb that I'd done. I was amazing. I was Superman.

Unfortunately, it's all a lie.

Over the course of several big mountain rides, I'd started to feel that

the numbers reported on Strava were quite a bit inflated, but I couldn't put

my finger on exactly how.

A week or so ago I posed about another ride, “Short but Intense Bike Ride in Northern Kyoto”, where someone commented

about the apparent discrepancy between reality and what Strava reported

(and hence what I claimed). This spurred me into investigating, and I've

spent the last week digging in, writing tracklog-analysis software, doing

tests, etc.

So, when I went out on a long ride last Wednesday, I brought an

arsenal of equipment with me, recording five separate logs with three

different GPS/GLONASS-equipped devices.

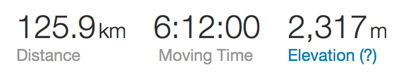

The trip ended up being my longest ride ever, about 125km (78mi), and

also had the most vertical climb I'd ever done in one day. Among the many ways I

recorded the trip's data, I used Strava's mobile

app on my iPhone 6+, and when I was done I had the app

upload all the data to Strava.

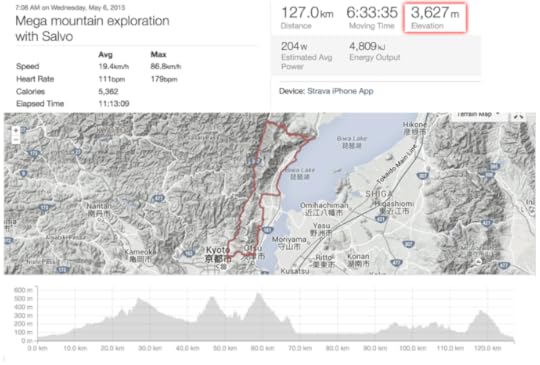

Here's what Strava reported about that trip:

Impressive!

but wrong

The elevation graph at the bottom is an accurate representation of the

11-hour ride, with four separate major mountain peaks transversed, along

with many little ones (though they each didn't seem little at the

time!).

Strava informs me that the trip encompassed an impressive 3,627m

(11,900') of vertical climb. It looks like I started at about 50m and initially climbed to about

500m, and from there went down and up quite a bit

— and believe me, I did — but looking

at the graph it's difficult to come up with a 3,637m sum for all the “up” parts.

In reality, I believe the vertical climb on the trip was about 2,225m (7,300').

First, let's look at why Strava's numbers are so wrong, then let's look

at how to get a better answer.

There are various ways a unit can record your elevation as you travel,

and all of them are generally untrustworthy. Modern units like an iPhone

or a dedicated unit like a Bad Elf GPS Pro+

have three methods to figure altitude: GPS,

GLONASS, and a

barometric altimeter.

GPS/GLONASS can be fairly accurate with your latitude and longitude, as I've discussed in prior

posts, such as

“Informal GPS Logger Test: iPhone 4s GPS is Shockingly Good”

and

“Another Informal Location-Logger Test”.

It's fantastically-amazing technology that is perhaps the only

time we come in contact with something that must actually take into account

Einstein's

general theory of relativity. But it's not perfect, and of the three

dimensions, elevation is by far the least accurate.

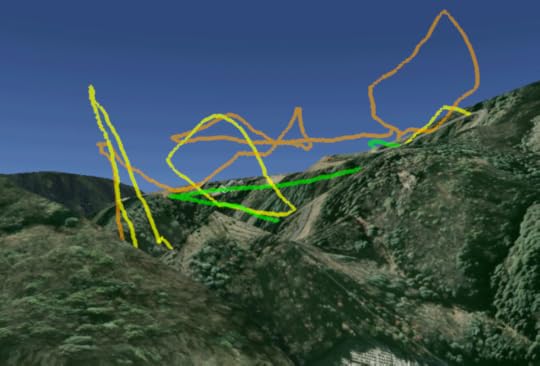

Consider these views of three GPS/GLONASS units' tracklogs plotted in Google Earth,

of various sections of last Wednesday's ride:

The three units rarely agreed with each other on the elevation, nor any

of them with Google data as seen in Google Earth, and they each in their

own way tended to wander off wildly at times. (The tracks, when viewed

directly from above, all matched up with each other and the road quite

well... it's only the elevation data that was, so to speak, all over the

map.)

When wishing to track vertical climb, the absolute accuracy of a unit is

not particularly important, it's the relative accuracy and stability that

are important, and it seems that barometric altimeters provide better results.

My first experience with a barometric altimeter, on a Garmin GPS unit a decade

ago, was very bad. If there was a breeze or you walked with the unit, it

would record a non-trivial change in elevation (up or down, depending on

how the unit was physically angled relative to the air movement). It was ridiculous.

Things seem better now. On last Wednesday's trip, I had two barometric

altimeters with me, the one in my iPhone 6+, and another on a Bad Elf GPS+.

Here's their plots for the last section seen above:

Anyway, a naïve calculation of vertical climb looks at each data point

and, if the elevation of a point is higher than

the previous point, add the difference to the total. Minor errors that

result in small fluctuations over the short term result in wildly-inflated

overall results, but one can smooth the raw data (e.g. with a moving average) to get more realistic results. That's

apparently what Google Earth does, so let's look at what it calculates for

each of my five tracklogs:

UnitTypeGoogle-Earth Vertical-Climb Calculation

BadElf GPS+ GPS/GLONASS3,479m11,414'

BadElf GPS+ Barometric 2,174m7,133'

Garmin eTrex 20GPS/GLONASS3,265m10,712'

Apple iPhone 6+GPS/GLONASS2,215m7,267'

Apple iPhone 6+Barometric 2,009m6,591'

That's quite a range of results from the very same trip. Which is correct?

Frankly, probably none of them.

As we'll see later, there are techniques we can use to eke out some

fairly reasonable results, but first let's see what Strava actually

does...

What Strava Does

Strava's iPhone app has access to both iPhone altimeters (barometric and

GPS/GLONASS), but in the end it uses neither. Rather, it throws away that

elevation data and instead relies on its own database of elevation data

(likely the same data that Google uses to show 3D elevation in Google

Earth).

Strava's approach may well be fine in generally-flat areas, but it produces

ridiculously-overinflated results in the mountainous areas I've checked, and

it's easy to see why...

I created some software to analyze the tracklogs, smooth local

irregularities, and present uphill sections in red and downhill sections in

green. Let's look at the mountain shown in this article's lead photo, a

long climb followed by a long, enjoyable descent down the other side...

Reality

red means uphill, green means downhill

Both the climb and the descent were quite straightfoward;

the climb was a solid climb without any downhill breaks, and the descent was a solid descent

without any uphill sections. That's why the ascent is a solid red line above, and the

descent is a solid green line.

Now, let's look at how Strava sees it, as well as all my data sources...

from Strava's elevation data

Bad Elf GPS+ (using its barometric altimeter)

Bad Elf GPS+ (using GPS/GLONASS)

iPhone 6+ using GPS/GLONASS, as recorded with the Galileo Offline Maps app

Garmin eTrex 20 (GPS/GLONASS)

iPhone 6+ using barometric altimeter, as recorded with Abvio's Runmeter app

span.b015 { font-size: small; padding: 2px; border: gray 1px solid }

Strava

- BE (baro)

- Garmin (GPS)

- BE (gps)

- iPhone (GPS)

- iPhone (baro)

mouseover a button to see that image

The Strava data shows many ups and downs on both sides of the mountain... ups and downs that

simply weren't there. It's easy to see why when you look at the mountain in Google Earth (which I believe

uses the same elevation data) from the side. Here's the side of the mountain that I rode down:

very-3D mountain pressed into a mostly-2D face

The road appears undulate up and down as it makes overall progresses lower, and to Strava,

the “ups” count as vertical climb:

Strava “detects” many false climbs (216m/700' just in this view alone)

Of course, the road doesn't undulate up and down (it progresses “monotonically” down),

but it does undulate

side to side around ravines cut into the side of the mountain by eons of water and wind. You can sort of see the proper undulation in this path created with a barometric altimeter:

descending around ravines that do exist, but which aren't presented in Google Earth

I should be clear that I'm not complaining about Google... the resources

they've freely gifted to the world in Google Earth and Google Maps

continues to amaze me, and I'm extremely thankful for them.

I'm not quite sure that I'm complaining about Strava. Perhaps these

easily-avoidable inflated results are particular to my area of Japan, and

the rest of the world enjoys added accuracy due to Strava's policies. I don't know. But I do know

that a lot of folks around the world complain

about Strava's inflated elevation claims, so at least I know that I'm not

alone.

So How Can We Do Better

First of all, I should note that Strava does respect the recorded

elevation in some situations where it recognizes that the data was recorded

with a barometric altimeter. Their own iPhone app, however, either doesn't

use the barometric altimeter or doesn't notice that it does, so users get stuck

Strava's elevation data.

Where Strava does accept a device's elevation data, they offer the user

a way to get “corrected” data, whereby Strava throws away the user's data

and replaces it with their inaccurate elevation-database data. This results

in a much less accurate result for many folks, but they offer no way to

undo this action, so if you bump the link by accident, you're hosed.

They also don't allow you to toggle between your device elevation data

(barometric or not) and their data. It seems that they really want to push

their data, and who can blame them? Folks like me early on, ignorant of the

hyper-inflated vertical-climb data, get an ego boost from seeing the big

numbers. I suppose boosted egos help their business interests.

(I'm thankful for their service, which I have enjoyed without cost. I just wish this aspect were better.)

Luckily, one crack in their anti-reality armor is that they allow geeky

types like me to create tracklogs with other devices, then modify

the tracklog to force Strava to accept the elevation data as is, and upload

that.

Massaging Tracklog Data

I've spent the last few days writing software to analyze tracklog data,

to smooth it out, and to derive meaningful information from it.

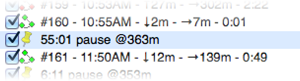

The first step is to identify when you're stopped, because if you're not

moving, you should have no elevation gain or loss, no speed... nothing.

You're stopped.

Unfortunately, GPS receivers tend to record drifting locations when

stationary, such as the hour I spent visiting

someone (this

sweet lady) in the mountains along the way on Wednesday's long ride:

this is what an hour's complete lack of movement looks like

My analysis figured out that all that movement didn't really get me anywhere, so it filters it out

and marks the stopped location with a little blue ring:

“pause” detected

I have my software note the length of the pause in the KML label, like this:

My pause detection seems to be highly accurate, and I compared its

results with the reality that I remembered on the trip, and it's pretty much perfect. It even accurately detected a 10-second pause at an intersection waiting for a few cars to clear

before I crossed over:

10-second pause for traffic

45-minute pause wandering in and around a convenience store

while waiting for a friend to join me on the trip

Then my software goes through the entire trip to find the highest peak

and the lowest valley, and pin the elevation at those locations. That

divides the whole trip into four parts, each of which is subject to the

same analysis, and this analysis recurses (repeats onto itself) over and

over until the difference between a local peak and a local valley is almost

within the range of noise.

Once all these local peaks and valleys are found, the elevation of all

the points in between are smoothed using a moving average. The elevation of

each peak/valley point is left undisturbed, and it's the elevation rise

between them that adds up to the trip's vertical climb.

After all this analysis, the software prepares a KML file that shows

the trip, with red lines for climbs, green for descents, and white for flat sections

(and, optionally, the blue circles for pauses). Here's one view of the second half of my trip:

Looking North up the eastern side of Lake Biwa

The red line at the far right ends at the Shirahige Shrine (seen here in the

report on a ride two weeks ago), which we visited briefly after having come

over the mountain, before turning south to ride home.

The distance from the shrine in the background to the spot in the

foreground where the route turns 90 degrees and pitches up into the

mountains is 30km (18mi) as the crow flies, which I mention for scale.

Here's the whole 125km (78mi) trip:

If you'd like to see it yourself, you can download the KML file

(with pauses /

without pauses)

to view in Google Earth.

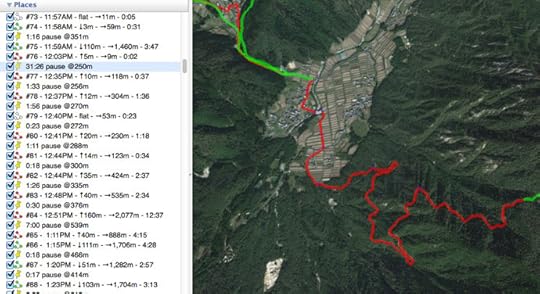

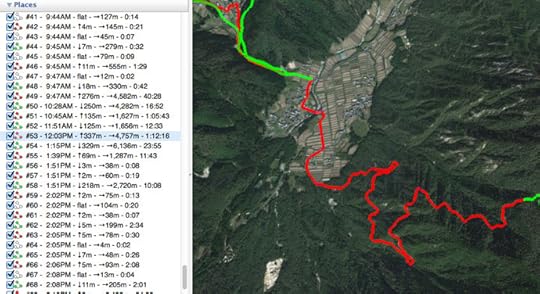

The “with pauses” view is best for me when I want to “relive the experience”, and I can see,

for example,

that I stopped for half an hour — 31:26 — to eat lunch (at this place

that I last visited seven years ago), and then progressed up the mountain stopping at intervals

for photos, to check directions, or to fix a popped chain.

That view is pretty cluttered if all I want to do is analyze whether the vertical-climb data seems reasonable,

so for that the “without pauses” version is better:

The duration includes all the intervening pauses, rendering it fairly

meaningless, so I should probably simply remove it, but at the moment it's

still there.

Anyway, I did this analysis on all my tracklogs, and found that the one produced

by the Bad Elf GPS+ with barometric altimeter seemed to most match reality, so that's the one

I consider, relatively speaking, “correct”.

And after all this analysis and cleaning and smoothing, I'm left with a tracklog that I (relatively speaking) trust,

so I prepare it so that Strava won't override the elevation data, and upload it. Strava doesn't know that I've

grooomed it, so it does its standard processing, and comes up with this:

They somehow came up with an extra 100m of vertical gain, but since I

truly don't know what the actual value is, I can't say that they're any

less wrong than I am.

So, now that I have the ability to derive a realistic vertical-climb

value, to be honest with myself I must go back and correct prior trips:

table#t2568a td:nth-child(2) { text-align: left; padding-left:1em; padding-right: 0.5em }

table#t2568a td.ft { font-size: small; white-space: no-break }

Date

Event

Vertical Gain

Claimed at the Time

Vertical Gain

Realistic Value

Strava

Inflation

(in feet)

Jan 24

My first tentative outing on bike

N/A

685m

→ 2,090'

Feb 7

My first real mountain ride

3,850m

1,517m

274%

12,630' → 4,620'

March 3

Kuyataki Waterfall with Manseki

762m

540m

141%

2,500' → 1,650'

March 4

Group ride southeast of Kyoto

1,787m

1,282m

140%

5,860' → 3,910'

April 16

“Highly Visible” mountain ride

1,607m

1,180m

136%

5,270' → 3,600'

April 23

Pleasant 105km lake ride

1,300m

?

4,200' →

April 29

Coffee at Cowbell

1,720m

991m

174%

5,600' → 3,020'

April 30

Revisiting my first big mountain ride

3,159m

1,609m

196%

10,360' → 4,900'

I didn't have a good barometric-altimeter tracklog for one of the rides.

The amount of “Strava inflation” is shocking. If I could solve this

problem for myself in a couple of days, you'd think a real company with

presumably smart folks could come up with something.

Anyway, I'll need to find a better app for keeping tracklogs on the

iPhone, one that lets me record both the GPS/GLONASS elevation and the

barometric elevation, and also my heartrate. As it

is now, I'll use a klugy mixture of

various devices and combine all the data myself, massage it, smooth it, and

then send it to Strava.

If they ever get around to addressing this, I suppose that would be a

good time to bring up the next issue: they ignore elevation changes when

calculating distance. They correctly

note that the difference is perhaps at most 2%, but on a 100km ride that can still

be over a mile wrong.

Overall, I guess Strava is just not as anal about statistics as I am...

Jeffrey E.F. Friedl's Blog

- Jeffrey E.F. Friedl's profile

- 13 followers