Freed Men

A number of the heavy-weights of Roman literature were freed slaves. Terence, for example, was an African slave, brought to Rome by a senator. His master became impressed with his literary talent and, insensitive to the demotion in quality of life and pay it would mean, freed him from slavery to become a playwright. (Terence wrote six plays and died young.) Horace, one of Rome’s most revered poets along with Virgil and Ovid, proudly admitted he was the son of a freed slave. The great Stoic philosopher Epictetus was himself a freed slave. And these writers overcame the disadvantages of slavery to influence the course of intellectual history—and even cast their shadows into the political sphere. The editors of the Dover edition of Epictetus say “Epictetus was considered the greatest of the Stoic philosophers by Herodes Atticus, a teacher of Marcus Aurelius,” who ruled Rome in the second century C.E. and wrote perhaps the most famous works of Stoic philosophy we have. Our academy labels Horace and many other Roman writers ‘dead white males’ of the ruling class and so casts them aside. Most people won’t have even heard of Epictetus. The not ignoble idea is of course to give a voice instead to those who’ve been historically deprived of one. The irony is: who better meets this exact criterion than a poet like Horace or philosopher like Epictetus! A ruling class can impose no more thorough a silence on the powerless than through slavery, and Horace shares this heritage with the great African-American writers of today, only it was even closer to him—his father was a slave! Virgil was not a slave (though he did come from Gaul), but he was the sort of un-elitist man to give a chance to the son of a freed slave. Virgil gave Horace his shot by introducing him to the great Roman literary patron Maecenas. You see, the enlightened Roman Republic wasn’t just good for aqueducts. It was good for outsider literature too; its finest writers brought to their work a worldview from outside Rome’s ruling class. Epictetus’s history as a slave has a special importance to his work. It not only marks him as an outsider but also, I would argue, forms the basis of his Stoic philosophies. His writings frequently criticize the institution of slavery—clearly, he didn’t forget about his early life as a slave—but more importantly the condition of helplessness of which slavery is the apogee colors all his thinking. He returns again and again to the theme of freedom of mind versus that of body; every line of his work speaks to all that we can’t control in life and seeks to define the correct terms of happiness and freedom given this limitation. A collection of his teachings called the Enchiridion, or “Manual,” begins:

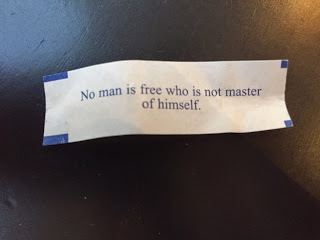

A number of the heavy-weights of Roman literature were freed slaves. Terence, for example, was an African slave, brought to Rome by a senator. His master became impressed with his literary talent and, insensitive to the demotion in quality of life and pay it would mean, freed him from slavery to become a playwright. (Terence wrote six plays and died young.) Horace, one of Rome’s most revered poets along with Virgil and Ovid, proudly admitted he was the son of a freed slave. The great Stoic philosopher Epictetus was himself a freed slave. And these writers overcame the disadvantages of slavery to influence the course of intellectual history—and even cast their shadows into the political sphere. The editors of the Dover edition of Epictetus say “Epictetus was considered the greatest of the Stoic philosophers by Herodes Atticus, a teacher of Marcus Aurelius,” who ruled Rome in the second century C.E. and wrote perhaps the most famous works of Stoic philosophy we have. Our academy labels Horace and many other Roman writers ‘dead white males’ of the ruling class and so casts them aside. Most people won’t have even heard of Epictetus. The not ignoble idea is of course to give a voice instead to those who’ve been historically deprived of one. The irony is: who better meets this exact criterion than a poet like Horace or philosopher like Epictetus! A ruling class can impose no more thorough a silence on the powerless than through slavery, and Horace shares this heritage with the great African-American writers of today, only it was even closer to him—his father was a slave! Virgil was not a slave (though he did come from Gaul), but he was the sort of un-elitist man to give a chance to the son of a freed slave. Virgil gave Horace his shot by introducing him to the great Roman literary patron Maecenas. You see, the enlightened Roman Republic wasn’t just good for aqueducts. It was good for outsider literature too; its finest writers brought to their work a worldview from outside Rome’s ruling class. Epictetus’s history as a slave has a special importance to his work. It not only marks him as an outsider but also, I would argue, forms the basis of his Stoic philosophies. His writings frequently criticize the institution of slavery—clearly, he didn’t forget about his early life as a slave—but more importantly the condition of helplessness of which slavery is the apogee colors all his thinking. He returns again and again to the theme of freedom of mind versus that of body; every line of his work speaks to all that we can’t control in life and seeks to define the correct terms of happiness and freedom given this limitation. A collection of his teachings called the Enchiridion, or “Manual,” begins: Of things some are in our power, and others are not. In our power are opinions, movement toward a thing, desire, aversion (turning from a thing); and in a word, whatever are our own acts: not in our power are the body, property, reputation, offices (magisterial power), and in a word, whatever are not our own acts. p. 1, Dover Thrift EditionFrom this premise he draws the conclusion that one can only secure happiness “by withdrawing from the things which are not in our power, and by placing the good and the evil only in those things which are in our power.” (p. 13) The job is therefore to be master over one’s own thoughts, not one’s fortunes, over one’s deeds but not over their consequences. It is what might be called the art of assent, as it’s put in the 177th “fragment” attributed to Epictetus (p. 56). Paleo-Christian monks handed down these fragments across the centuries like Roman pottery, getting more and more broken with each transfer, and it’s just this sort of shabby treatment that’s out of Epictetus’s control and to which, I imagine, Epictetus therefore grants a certain assent. “Let it be,” “Let it go,” “It is what it is,” and like sayings seem to me to have this kind of assent in mind. It’s what I have in mind with my kids when I decide to pick my battles and give in. You want ice cream before dinner? OK, yes. The blessed freedom of it! The Stoic philosophy is not idle speculation but rather a discipline. It’s meant for practical application to help you live a better life. The Stoics find happiness in the regulation of one’s feelings instead of in victory or salvation in realms outside the self. The idea belongs to a humanistic, rationalist movement of two millennia that begins with Socrates and ends, perhaps, with Freud. Could there be any talking therapy without a Stoic expectation of happiness attainable from within? The pleasures of Stoic self-sovereignty allow the gladiator-slave Spartacus, at the end of the 1960 movie of that name, to conquer his enemy even as he is crucified by refusing to answer his interrogator’s question. As screenwriter Dalton Trumbo said, it was a movie about men “who in the end preferred to die as free men than live as slaves.” In this calculus, the freedom given to all human beings as a birthright trumps even death. But the pleasures of a free mind exceed Spartacus’s right to disobey—they include also a freedom of imagination. André Breton, the father of surrealism, makes a Stoical retreat from reality towards an inner freedom of thought that knows no bounds. He writes: “Among the many misfortunes to which we are heir, it is only fair to admit that we are allowed the greatest degree of freedom of thought.” (Breton, Manifestoes of Surrealism, p. 4)

Published on April 25, 2015 19:08

No comments have been added yet.

Austin Ratner's Blog

Untimely thoughts on books both great and supposedly great.

- Austin Ratner's profile

- 32 followers

Austin Ratner isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.