National Poetry Month: Guest Post From Michalle Gould: When Is It Enough?

Putting a book of poetry out on the world can feel like an unusual way of testing your personal relationships. It is hard not to find yourself asking questions that it would probably be better not to think about. Who has bought my book? Have the people who bought my book actually read my book? Did they like it? Did they hate it? Did they finish it? When will people start adding reviews on goodreads? When will people start adding reviews on amazon? That person said they were going to buy my book, but it doesn’t seem like they really have. How can I get more people to buy my book? How many times can I talk about it on facebook without people hiding me? How many times can I talk about it on twitter without people unfollowing me? Am I turning into a monster for thinking about any of this? Is this something I should be admitting in writing?

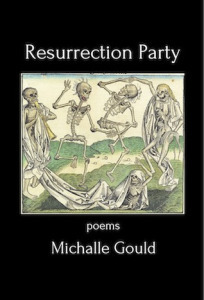

Silver Birch Press, August 2014.

But it’s your book! You’ve worked on it for so long! In my case, I worked on it for nearly fifteen years! Back in 2002-2004, just after I finished my MFA, everything seemed to be headed in the right direction. My poems were published in Slate, New England Review, and Poetry, all completely out of the slush pile. My manuscript was a semi-finalist or finalist in a few book contests and solicited to enter an open reading period. I felt sure that my book was about to be published. And yet for whatever reason, I found myself slowly but surely submitting less and less. I still entered contests but fewer and fewer. I still sent my work out but far less frequently. It is hard to put my finger on why, but I think one reason was a fundamental crisis about the direction those achievements were taking me and how that might be affecting my writing. For most poets who enter MFA programs, the end goal is clear – to eventually publish a book. But a part of me was unsure that I was entirely ready, as well as about the effect that giving the book primacy as the end-goal of writing, the mark of “success,” might be having on my writing of individual poems.

Publishing a book feels so final – it can appear to impose a sense of conclusion upon a body of work, to harden it into a structure of meaning that may not have existed when you were writing its individual components. Readers of a book will inevitably look for overall themes and relationships between the poems, to presume that you had some overall intention in mind for the poems taken as a whole. Furthermore, the contest system for getting first books (and lately second and third and all books) published may subtly encourage writers to anticipate this by consciously linking their poems – whether it is the truth or not, it can definitely feel that a project book, defined here as a book of “poems that surround a central idea,” has a significantly better chance of catching a screener or final judge’s attention than a book of good but unrelated poems.

I worry that this distorts the type of poems that are being written, that this can subtly steer writers away from poems that do not “fit,” that do not deal with an identifiable theme or subject. At times I could feel myself writing “to” the poems that already existed in my book, not wanting to expend time or energy working on something that wouldn’t have a vessel to contain it. While that was certainly my own choice, I found the pressures and environment that shaped that choice frustrating. I want to emphasize that I am not criticizing project books in and of themselves, just the possibility that poets who aren’t suited to that format may be pushed to write them by the current publishing landscape.

In some ways I resist the book as the primary “unit” of poetry. It is more natural to me to compare a favorite poem and a favorite novel than to think offhand of a favorite book of poems. A poem is a complete entity to me in the same way that a novel is a complete entity. I think this is also often true of those whose primary relationship to poetry is as readers of it rather than writers. This may be part of why sales of books of poetry are generally considered to be very low, despite the fact that poem-a-day sites and favorite poem projects are so popular, despite the prevalence of individual poems on trains and in bus terminals and readings at weddings and funerals.

So where does that disconnect arise from? And if people are so disinterested in buying poetry books, why try to publish one at all, especially knowing that means subjecting yourself to the somewhat degrading-feeling cycle of questions listed above, the necessity to self-promote even though, as described vividly by poet Tim Green here, you will generally be promoting your book mostly to “1,000 other poets trapped in the same nauseating self-promotional pie-eating contest,” with their own book to promote and their own poet friends’ books to read and no time and energy for yours, rather than the broader audience that exists for novels and memoirs.

Although writers, on the one hand, share the responsibility with publishers to think about the first question and how to change the situation as it stands, at the same time, I think we also eventually need to ask ourselves the question, “When is it enough?” When is it time to let go – to stop worrying about whether people are buying it, whether they are reading it, even whether they like it? It’s hard to do because it can feel like those things impact our ability as poets to publish other books in the future. But when the pain begins to outweigh the pleasure, there is basically no other choice than to return to the more fundamental and original starting point, the simple task of trying to write one good poem.

Michalle Gould.

Michalle Gould is a writer and poet who worked on the poems in RESURRECTION PARTY (2014) for some 15 years before publication. She currently works as an academic librarian in Los Angeles and is also writing a novel set in the north of England in the 1930s.