The Beginning of the End/The End of the Beginning

Aristophanes’ The Frogs tells of two boys playing near a stream who find a frog and, for fun, kill it. They killed the frog in jest, Aristophanes reports, but the frog died in earnest. People whose lives are diminished, ruined, or taken because of the ethos of the era in which they live are like Aristophanes’ frog. Impersonal forces of history may explain what happened to them, but their suffering and loss are real.

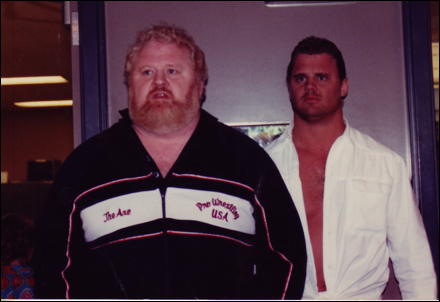

Eddy Jacks Jr., imitation son of the golden original, wrestled his last match when he was 32 years old. Almost since he had finished playing college football and washing out of the CFL, he had been touted as a Next Big Thing. Not the Next Big Thing, because he had a fair number of flaws1, but certainly one of many possible Next Big Things.

It could have happened a bunch of times, such as when he won the IIWF Intercontinental Title at age 24. The Internet smarks, obsessed with four-star matches and the Japanese “strong style” of working, made a big deal out of his victory: here was this kid who could flat-out wrestle, rewarded by a top-heavy, veteran-driven company with a poor reputation for handling young talent. His father, the original Eddy Jacks, was overjoyed. The imitation Eddy Jacks’ friends, most of whom were trying to enter the business themselves, were insanely jealous. He looked to all the world like a future star. What could go wrong?

Everything, of course. Junior’s first couple of title defenses were pretty lifeless, which was tragic given that they served as co-main events for the weekly television show. His big feud with Marty Warnett, a bland English technician who had served as the federation’s default Intercontinental champ for over a decade, generated exactly zero heat. Junior was wrestling then as an All-American blue-chipper, and Warnett was doing a typical European heel gimmick, and those styles didn’t mesh at all. Their work was believable, but their performances weren’t sincere. When it ended at WrestleWar XII, the imitation Eddy Jacks lost cleanly in the center of the ring. He had held the belt for exactly eight weeks, and now he was finished.

The funny thing was, Junior’s promo work actually got better after he left the Intercontinental title picture. The IIWF brought his washed-up father out of retirement and had him serve as his son’s abusive trainer, a role that fit the big man as comfortably as an old shoe. The Jacks Family found itself in a crowded tag team division. The Black Watch, a high-flying tag team from Scotland, was locked in an epic yearlong feud with the Baddest Thangs Running, and because the original Jacks had heat with one of the Thangs, they spent the better part of their run putting them over at house shows.

But people liked the Jacks Family, and their Jacks Family Values vignettes kept them going long after knee and shoulder injuries forced the original Jacks to the sidelines. Junior would go out to the ring, screw everything up, and then the original would hit his son’s opponent with a pair of brass knuckles. There was a Television Title reign mixed in there somewhere, but that strap had been so degraded by innumerable title changes that it was reserved solely for the comic relief guys. Jacks Junior, who hadn’t been booked to look strong in years, excelled at playing a loser–and that’s eventually what everybody came to think he was.

Four years after he entered the Double Eye, Junior’s contract expired. It wasn’t renewed. No reasons were given, and none needed to be: he had once been, in his the words of the original Jacks, “like a hot dog on a bun: on a roll,” but now he was about as valuable as last week’s advertising circular. His old man, whom Junior mostly but not completely detested, was no longer able to perform in any capacity and hung up the boots for good. He would occasionally drag himself out of the house for a one-off show with his kid in some Midwestern palookaville, but his cash value as an attraction had dwindled to nothing, too. The difference between the original Jacks and the imitation was that the original had been the undisputed World’s Champ back when that still meant something, even if he had only held the strap for a week, and the imitation hadn’t been anything at all.

For a while, Junior chased those ever-decreasing bucks. $300 to headline a show in Kalamazoo, Michigan for Great Lakes Championship Wrestling. $1,500 plus travel costs to lose to Tex Violence in a barbed-wire match in Japan that saw Junior’s eye knocked clean out of the socket. 2 Other engagements resulted in worse injuries, ranging from a torn rotator cuff (never surgically repaired) to the amputation of several toes. And so it was at age 32 that the imitation Jacks, already woozy from the semisynthetic opiods that were now his mother’s milk, botched the landing on a clumsy moonsault and wound up with a fractured hip.

Was it in vain? The best years of the imitation Jacks’ life were gone, spent chasing the legacy of an original who hadn’t been all that good in the first place. But the original had been a wrestler, which was the only thing that Junior had ever wanted to be. Junior was a wrestler too, by some accounts an especially gifted one, but now he wasn’t anymore. He had wanted to wrestle since he was five, started at 22, and never participated in another match after turning 32.

“I always kept coming to crossroads,” he told me a couple of weeks ago. “I always found myself on the cusp of something. But by the time I got there, the train had already departed. No matter how early I left, it was gone. I kept missing happiness by a few minutes each time.”

What does it mean, you have to ask yourself, to be so close to something that you can taste it, yet still so far from it that nobody would believe you were ever there? It was similar, Junior felt, to his college football experience: you always believed you were lying to people when you told them you had done it, like you were fudging the record merely by reporting it wie es eigentlich gewesen.

In his wildest dreams, the imitation Jacks would have wrestled a match so pretty that no critic could ever think past it. It would be the match of which no greater could be conceived; and at the precise moment he lost, his shoulders went pinned to the canvas for the “long three,” he would just vanish into thin air. There would be nothing left of him, no trace of his having existed at all. The match would linger in the minds of the fans who witnessed it, but they wouldn’t know what it was that they saw, not really. Their memories would amount to nothing more than a digital picture of a xeroxed copy of a stenciled mimeo of a carbon copy of this golden original, an event that, in the words of another famous wrestler, would be “often imitated but never duplicated.” He would have been his own man at last.

But forget that fantasy: Junior went on living, his dream deferred shriveling up like a raisin in the sun. The steroids he had abused in his twenties and thirties in order to remain viable in a sport dominated by giants had so weakened his heart, though, that he only had to endure two more decades of this. Then he was gone, that best friend of mine, and it was alright.

In no particular order: 1) In a sport dominated by giants, he was 5'10". 2) Although he was great on the mic, his talent never translated into a consistent “gimmick” that got over with the fans. He gained some traction in his twenties working as part of a father-son tag team with his mentally disturbed old man, and after his father’s demise he generated some heat in regional promotions with a “Gorgeous George” persona. 3) He was frequently injured and gained a reputation as something of a malingerer. Most of the injuries were related to his copious intake of oral steroids and other dangerous prescription drugs, which helped him maintain an impressive physique but exacted a high cost in other respects. 4) He refused to submit to the locker room hazing that other rookies experienced. Some promoters, particularly ex-wrestlers like Steve Kowalski, respected Jacks Jr. for this. Most, however, thought he was too big for his britches. 5) Much like his skinflint father, Jacks Jr. was incredibly cheap and argued about every paycheck. 6) Despite not being “one of the boys,” he was all too eager to job if the circumstances demanded it. After a few clean pinfalls, he was basically finished in the estimation of the fans. He really had no idea how to develop his reputation, assuming instead that his abilities would do the talking for him. They didn’t. 7) He was kind of an asshole to the guys he worked with, always forcing them to wrestle his plodding, ground-bound style of match. 8) He managed to blend a sense of entitlement, a sense of false modesty, and a tremendous inferiority complex into a total package of midcard loser-dom. 9) He had been horrifically abused as a kid, though nobody save yours truly knew this, and as a result conducted all his affairs with a sense of fatalism that would impress even a put-upon 19th century Russian serf.

YouTube that, yo. Shit’s nasttteeeee.

–Umma Beachman

Oliver Lee Bateman's Blog

- Oliver Lee Bateman's profile

- 8 followers