Bob Horner

(ATL 1978-1986, YAKULT/NPB 1987, STL 1988), .277/.340/.499, 1047 H, 218 HR, 1978 Rookie of the Year, 1 All-Star Game

The story of Bob Horner might be a tragic one if more people knew it. He was one of many Arizona State products to strike it rich in the majors, hitting 58 homers during his time at the school and getting drafted by the Braves with the first overall pick in the 1978 draft. He didn’t spend a day in the minor leagues. In just a little over half a season, he hit 23 home runs, slugged .539, and won the Rookie of the Year award over Ozzie Smith, a man who went on to have a far more enduring career.

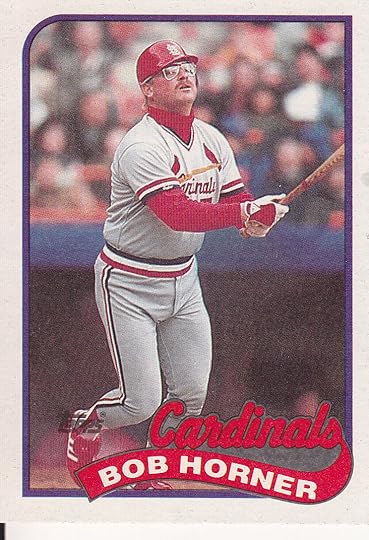

But just how tragic was Horner’s story? He hit 218 home runs in Major League Baseball and 31 more in Japan. Except for his last season, he was a consistent producer at the plate. Sure, he gained weight, switched positions from third base to first because he was terrible in the field, and suffered a career-ending injury with the Cardinals in 1988. In spite of that, his career spanned a decade, he’s considered one of the greatest college players in the history of the game, and there are literally millions of his 1989 Topps card in circulation. In that photo, where he’s wearing huge 1980s square-rimmed glasses and an ill-fitting Cardinals uniform, resides his such timelessness as he possesses: we remember Horner, and by we I mean I, as this thick-bodied, washed-up athlete hanging on for one last crack at the piñata.

When greatness is measured in 500-homer and 20-season increments, ten years of sustained productivity doesn’t represent failure, only tragedy. How close Horner came to fulfilling his g*d-given talent is unclear. One argument is that he fulfilled all of it, that we can’t do any more than we’ve done, that counter-factual history is a parlor game played by losers. He got fat and hurt his shoulder because genetics dictated that he would, after which his body wouldn’t. The opposite argument is that every moment of life is a freely-elected compromise between competing interests, greatness being one of them. Were five hundred home runs more important than extra time with friends, or extra time spent watching Friends on television? Was the ability to pull a hot grounder out of the dirt at third more important than a dozen extra chili dogs at Atlanta’s The Varsity drive-in? With great talent comes the freedom to squander it, goes this narrative.

Each approach has its merits. The former seems more precise, more “scientific.” So that’s why it happened, eh doctor mister sociobiologist? The latter is more elegant. Among the most beautiful varieties of art is a wasted life. I didn’t pay much attention to Mike Tyson or “J.R.” Rider or “Doc” Gooden on the way up, but I sure as heck noticed them on the way down. Each year, you saw less and less of these guys, until, for one reason or another, there stopped being any there there. Along the way, their flashes of brilliance–a surprising knockout punch, a 360 jam after spending most of the game sucking wind on offense and staying invisible on defense, a no-hitter–reminded you of what once had been and what now was inevitably slipping away. Even as a kid, such thoughts brought a smile to my face. These people, memorialized on card stock like fossils in amber, were living reminders that their glorious 1986s and 87s and 88s would be no more. And neither, of course, would mine.

–Eddie Bookman

Oliver Lee Bateman's Blog

- Oliver Lee Bateman's profile

- 8 followers