National Poetry Month from Matthew Burgess: Let There Be Elephants, or What is a Poet?

When I walk into the 2nd grade classrooms where I teach poetry on Friday mornings, one of the first things I say is, “Repeat after me.” This might sound like old-school pedagogy, but our call-and-response is anything but: “I’m a poet / and I know it / I’ve got my whole life / to show it.” We snap in unison, then bring our fingers to our temples to activate the invisible switches of our imaginations. Sometimes I vary the chant or add an extra verse: “I feel it in the winter / I feel it in the spring / I feel it when I whisper / I feel it when I sing.” Though not much of a singer, I go for a big, ringing SIIINNNGGG! in the last line, and the young poets echo it back in a hilarious chorus. The point is to signal the transition to imaginative writing, to wake us up a bit, and to reinforce a truth that is often overlooked: all of us in the room are poets.

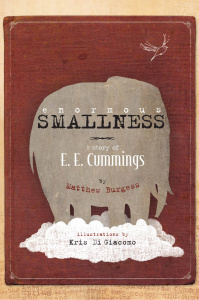

Enchanted Lion Books, April 2015.

Slow down, Fräulein Maria. What makes a person a poet?

I call these seven year olds poets in the same way that my Buddhist friend calls babies Buddhas, or in the way that Pablo Picasso asserted that “all children are artists. The problem is how to remain an artist once you grow up.” In other words, all the 2nd graders in the room possess poet-potential, and the surest way for them to access it is to believe wholeheartedly in their creative power.

Kenneth Koch had a hypothesis—that children know more about poetry than we often give them credit for—and he went into public schools to test it. What he discovered (and shared with the world in several exceptional books) is that children have plenty to teach us about the origins and usages of poetic language, and we would be wise to pay attention and to adjust our teaching methods accordingly. Koch was one of the founders of Teachers & Writers Collaborative, one of the first arts-in-education organizations in New York City, and I’ve been a poet-in-residence for T&W since 2001. I especially love teaching the early elementary students, because they continually surprise me, and they remind me again and again what a poet is.

Just last week, one of my 2nd grade students wrote this astonishing poem in response to E. E. Cummings’ “the sky was candy.”

Another student wrote about “puppies being born in rain drops,” and she was inspired by Cummings’ implicit permission (and mine) to place the poem on the page in a wildly inventive way.

During one of the season’s big snowstorms, another 2nd grade poet (who early in the residency asked me if “it was allowed” to make up words) wrote this poem using personification to describe winter.

Winter is a boy with rough weather.

Winter likes to play snowball fights

and destroy snow mountains.

Winter likes to eat snow burgers and drink

snowco-cola and hot snowcolate.

Winter likes to play snow and seek.

Winter lives in New Snowville, 35 miles from the snoway.

The snoway is in Snow City.

Snow City is in Snow State.

Snow State is in Snow Country.

Snow Country is in SNOWORLD.

Snoworld is in Snowuniverse.

So a poet is someone with a vivid imagination who takes pleasure in language. A poet is happy to leap over logic in order to dance to the music words make. If I read a line aloud—Elegant elephants eat eel eggs every Easter—poets don’t insist, “That doesn’t make sense!” On the contrary, poets want to jump in and keep the song going; they are likely to tell you about the jaguars jumping to Jupiter to drink the jujube juice. The movies in the minds of poets are still vivid, and their aliveness to language serves as perpetual refreshment to the image-making, song-creating mechanism embedded in everyone. Some of us let it fade from disuse, or from unintentional abuse at the hands of “grown-ups” who are all-too-often preoccupied with common sense, avoiding mistakes, and of course, test preparation.

Edward Estlin Cummings was someone who held on to this poem-making capacity for his entire life. He was born into a family that celebrated poetry, and both his parents nurtured his artistic development from a very young age. His mother, Rebecca, dreamed that her baby boy would grow up to become a poet, and she began recording his earliest attempts in a book titled “Estlin’s Original Poems.” As I write in my newly released picture book biography of the poet, ENORMOUS SMALLNESS: A Story of E. E. Cummings (illustrated by Kris Di Giacomo), Estlin’s first poem “flew out of his mouth when he was only three.”

Illustration by Kris Di Giacomo, courtesy of Enchanted Lion Books.

Once he learned how to write, Estlin took over and began keeping his own youthful journals, often decorating his poems and stories with drawings of elephants in the margins. I try to capture Estlin’s playful way with words in the following passage, citing the “great circus of his imagination.”

ENORMOUS SMALLNESS tells the story of E. E. Cummings’ development as a poet, and for me, part of the secret of his poetic gift was his ability to retain his childlike vision until the very end. That is to say: playful, open-eyed, and alive to the details of everyday life. The internationally celebrated poet lived in a tiny flat on a half-hidden cul-de-sac in Greenwich Village, collected miniature elephants, and famously wrote: “may my heart always be open to little birds who are the secret of living / whatever they sing is better than to know / and if men should not see hear them men are old.”

Illustration by Kris Di Giacomo, courtesy of Enchanted Lion Books.

The 2nd grade poets keep me young. Like E. E. Cummings, they know a thing or two about “the secret of living,” and they remind me what a poet is, or should be. A poet is a person who loves the way words sound and look, and who engages in the art of making objects out of words. It is the making that matters most—the great ongoing circus of the imagination. When my students finish their poems, they often hand them over to me without hesitation, and someone always requests that I read his or her poem aloud to my other classes. They get that the magic is in the making and the sharing, and in all of the enormously small ways that poems can wake us up.

And, by the way, if you are curious why Cummings’ name does not appear in lower case letters, read here.

Matthew Burgess.

Matthew Burgess teaches creative writing and composition at Brooklyn College, and he has been a poet-in-residence with Teachers & Writers Collaborative since 2001. His first full-length collection of poems, SLIPPERS FOR ELSEWHERE, was published by UpSet Press, and a children’s book titled ENORMOUS SMALLNESS: A Story of E. E. Cummings is newly released from Enchanted Lion Books. Burgess recently received his PhD in Literature from the CUNY Graduate Center, and his dissertation, titled “The Vastness of Small Spaces: Self-Portraits of the Artist as a Child Enclosed,” explores the significance of childhood space in the autobiographical works of Virginia Woolf, Denton Welch, Anne Sexton, Frank O’Hara, Alison Bechdel, and others. His poems, photographs, and essays can be found online at www.matthewjohnburgess.com.