Did Bullying Kill Lynda Burrill?

I knew something was deeply amiss with Lynda the day we met in 6th grade at Buckeye Elementary School.

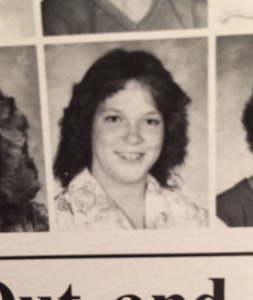

1982 Ponderosa High School Yearbook Photo

At recess, I’d taken out my hair combs and put them on the fountain in the school yard as I drank. When I looked up, they were gone. I told the teacher on duty what had happened, hoping someone would return them to her if they found them.

A girl in pigtails sidled up to me, her dark, ginger brown eyes as wide and bright as her lightly freckled smile. She held out her open hand, which cupped the two hair combs. “I found these. They’re yours, huh?” she said.

I took them from her, but before I could say thanks, she quickly added, “A friend would never have stolen them. A friend would find them and return them.”

A friend? Or someone so desperate to make a friend she’d steal something and pretend to “find” it? The whole exchange made me feel uneasy. Later, I asked someone who she was. “Her name’s Lynda Burrill,” another girl told me, and nothing more.

I stayed far away from Lynda after that.

Not that I would have come in contact with her much, anyway. We had no classes together in 6th grade. We then went on to different junior high and high schools. I went at Oakridge High School in El Dorado Hills, where I was relentlessly bullied my freshman year. But I had a few good friends, a couple of loving teachers, and my music, which saved me. I was raised a classical musician. I’d already played in both orchestras and bands. Music was my life. So when Oakridge lost its band teacher my sophomore year, the school district allowed me to attend neighboring Ponderosa High School, which had award-winning marching and symphonic bands. I loved the school. I had my first boyfriend, a hilarious band teacher, and zillions of geeky new friends without a bully in sight. It was a dream come true.

Lynda was also at Ponderosa.

Because our last names fell into the A’s and B’s, Lynda and I shared homeroom together. While I had lost weight, she’d gained some, I noticed, and seemed to be an outcast. I’ll never forget how the boys tormented her, in and out of class. Girls, too. About her grooming. Her clothes. Her weight. Although nothing seemed that egregious to me, anything was apparently fair game. She looked exasperated most of the time and tried to dish it back as fast as they served it. Just before Christmas break, someone in homeroom handed her a wrapped gift. Astonished, she accepted the gift and opened it.

It was a bar of soap.

Her head fell on the desk into her arms.

My heart ached for her. I would have consoled her, as I had fellow outcasts at Oakridge, but I remembered those hair combs. I didn’t care what other people would have thought if I’d befriended her. What scared me was that her desperation for love was so profound that it drove her to do — or at least say — things that were seriously inappropriate. What else would she do to “prove” her friendship?

When Oak Ridge High School restored its band program the next year, I had to return. I then suffered some of the worst bullying of my school years, mostly at the hands of jocks. (One of my bullies grew up to be a professional baseball player and is now married to a former Playmate. Nice for him, eh?) After a particularly scary incident on the last day of school, I used the bullying as a legal chip with school officials to return to Ponderosa High School for my senior year.

When Oak Ridge High School restored its band program the next year, I had to return. I then suffered some of the worst bullying of my school years, mostly at the hands of jocks. (One of my bullies grew up to be a professional baseball player and is now married to a former Playmate. Nice for him, eh?) After a particularly scary incident on the last day of school, I used the bullying as a legal chip with school officials to return to Ponderosa High School for my senior year.

I was thrilled to be back at my beloved “Pondo.” Marching band, jazz band, symphonic band. Pondo not only had a spectacular music program (and still does), but for me it was also gloriously bully free.

On August 24, 1984, just days before school started, I picked up my family’s copy of The Mountain Democrat to read the devastating headline.

Police Ask for Help in Murder Cases

…Denise Galston, 14, and (Lynda May) Burrill, 18, are dead. Their skeletal remains found in the Sly Park area were identified through dental charts and the announcement of their identities made earlier this week.

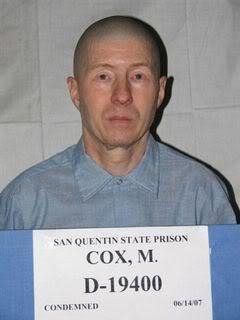

The parade of grisly headlines that followed revealed Lynda was the victim of a triple homicide. She’d disappeared on June 29, 1984 from a popular hangout called The Bell Tower on Main Street in Placerville, CA, where she was last seen talking with a 27-year-old man named Michael Anthony Cox — a man who, when he was 18, had allowed his 3-year-old half-sister to drown within arm’s reach.

(Motherfucker)

According to testimony, he’d once commented to another woman about Lynda that “girls like her needed to be eliminated.”

On November 29, 1985, Cox was convicted and sentenced to death for the 1984 first degree murders of three teenage girls — Denise Galston (14), her sister Debbie Galston (14), and Lynda Burrill (18) — with the special circumstance of multiple murder. He allegedly stripped and bound each girl before raping and stabbing them, leaving them to bleed out on the cold, dark forest floor. To this day, he sits on Death Row.

As I read the news articles, I realized for the first time that Lynda had already been held back a year in school before the hair comb incident. More fuel for the bullies.

When I think about Lynda, I remember a slightly heavyset teenager, pale, freckled, wearing a white dress dotted with flowers, hurrying across the campus to get to her next class. I don’t recall any smells, or that she looked significantly different from anyone else. Even her haircut seemed fairly de rigueur for the time.

So, I’m not sure why she was singled out. Regardless of her perceived faults, if everyone had been kinder to Lynda — schoolmates and family alike — might she have chosen better friends? Would she have still connected with a bizarre, cold-blooded predator like Michael Anthony Cox? She got in the car of a man who kept a buck knife in the visor to “prove” her friendship to him. We know how he rewarded her.

That desperation for love. The cruel denial of it.

I don’t know ultimately what confluence of events led Lynda to die on that forest floor soaked with her blood. Perhaps it was like Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express. Everyone played a role in delivering her demise. Family. El Dorado County officials. Ponderosa teachers. Her fellow students.

Me.

But I do know we failed. And we have to do better.

Innocent lives depend on it.