Jorie Graham

�� �� �� �� �� ����Jorie Graham’s From The New World has been hanging around me for the last while, hitting me up for the readerly equivalent of a thousand or so bucks of attention: you don’t dip into Graham as you do other poets, or I don’t, anyway (you can, obviously���it’s just text, black on white���but for me the return on investment re her work increases dramatically with quiet attention. That’s a long way of saying: there are few punchy, pitchy bits you leave one of her poems with; mostly you feel held against or under a beautiful water, and���unlike water���the longer you’re under/against, the bigger the oh on release). Plus also: I’ve read all her stuff, and part of my reluctance to dance into the book had to do with what the TOC hipped me to: my favorite of her books, 2002’s Never, is radically underrepresented (six of the poems in From The New World are from Never; Materialism‘s got six as well, so, I guess, someone else can write the mournful lament about that book’s shortchanging), a problem I didn’t even want to much contend with.

�� �� �� �� �� ����Jorie Graham’s From The New World has been hanging around me for the last while, hitting me up for the readerly equivalent of a thousand or so bucks of attention: you don’t dip into Graham as you do other poets, or I don’t, anyway (you can, obviously���it’s just text, black on white���but for me the return on investment re her work increases dramatically with quiet attention. That’s a long way of saying: there are few punchy, pitchy bits you leave one of her poems with; mostly you feel held against or under a beautiful water, and���unlike water���the longer you’re under/against, the bigger the oh on release). Plus also: I’ve read all her stuff, and part of my reluctance to dance into the book had to do with what the TOC hipped me to: my favorite of her books, 2002’s Never, is radically underrepresented (six of the poems in From The New World are from Never; Materialism‘s got six as well, so, I guess, someone else can write the mournful lament about that book’s shortchanging), a problem I didn’t even want to much contend with.

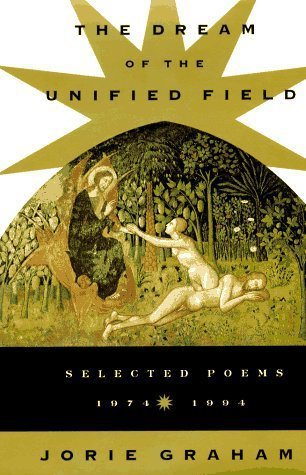

I’ve written elsewhere about the glories of Never, and my anxiety about its lack, or anyway thin showing in this new Selected (her first, Dream of the Unified Field, hit in ’95), is that it’s one of the most glorious and somehow beautifully desperate books I’ve ever read. It hit at a specific moment for me: I had doubts about if contemporary poetry was even bothering to attempt to Really Connect in intellectual/emotional/moral ways, as, say, Stevens or Eliot or Frost or Bishop or Dickinson had, and Never offered the till-then (and still-now) biggest yes re that question. It’s terribly, achingly, shatteringly about connection (there’s a sidebar here available, re Graham’s biography, and how Swarm [itself represented by seven poems in New World] and Never, released in 2000 and 2002, repectively, were [presumably] composed at the time of the dissolution of Graham’s marriage to James Galvin and her marraige to Peter Sacks, and the fact that Swarm is among the murkiest documents in American literature [one could/should open it at random and count the number of words that are not bracketed, broken-off, typographically whispered, it feels] while Never is so hungrily revving for Connect, Touch, Share…anyway, that aspect exists, however one wants to slot it). Never is also, I think, among the least fussy of Graham’s books: one needs know nothing, not myths or artists or theorists, nobody: it’s a natural book. It’s messed-with, in lineation, but one needs no extra context to apprehend the poems.

What’s interesting, though, about Graham���as with any Great writer���is that she’s offering multitudes to each of us, all the time. What I read Graham for was this linguistic and self-based experiment���what Dan Chiasson in his unbelievably great review of The New World called her “brilliantly dissected subjectivity”���which I thought culminated in Never: that book read as if she were reaching clearly, deliberately out, to rattle the reader’s conception of how poetry could connect reader+writer, what it could ask of both of us in that shared moment of/momentous context. But of course she was doing other stuff, in Never and before���was talking about myths and paintings, about religion and literature, about America and nature, and nature, and nature���and for all the folks who like me read her to get some connective charge in certain terms, plenty others I’m sure were getting other stuff. And there was, always, plenty: Graham’s maybe intimidating for how much she puts in, her willingness to idea-check anyone, her ongoing comfort with writing from and in and toward what she called a Big Hunger: she’s never written poetry that functioned like New Yorker cartoons, sweet things that dissolved the minute the page flipped, and her stuff, at its gnarliest, is never ever (I don’t think anyway) opaque or idea-checking for points or some such: she wants to hit big, to be as specific as she can, to touch on Big Ideas, and (I believe) she does, and, in doing so, she goes anywhere: read the Notes of any of her books for a lesson in audacity.

And so now there’s From The New World, a book spanning almost forty years of writing, and what’s clear is that Graham’s had any number of Projects/Agendas/Obsessions in her work (if you dislike thinking like that, fuck off: any artist will, through her work, make clear���if the work’s looked at in a swath���what she’s centrally focused on, preoccupied by, and to pretend otherwise is so dumb I here apologize for even bringing it up, but I’ve got a kneejerk thing re: using any of those terms since it seems my age-bracket is intimidated by acknowledging such obviousness). The Project/Agenda/Obsession of hers I like and first fell for, the one I think best articulated in Never? The one about subjectivity? That’s simply one of many threads through her work, and it’s not at all the central thread in her work���at least the central thread as it’s articulated in *this* selection of poems from all the books (which selection, automatically, radically cleaves the scope of the books themselves [meaning there are several possible Selecteds to create from Graham’s oevre, each of which would paint a revised scene re: what she’s been Doing]). This is not at all a criticism, at all: it’s an attempt to note that the poems on offer here work together���beautifully, one quickens to add���to paint a picture of a poet who’s been for four decades fixated on questions about the world itself and living in it, about drawing some connective thread through the astonishing balances of existence. And, as Sea Change and Overlord and Never and to some degree PLACE make clear���along with the four new poems included in From The New World (poems I, unlike Chiasson, don’t find to be some of her best: the one he quotes, to end his article, is incredible, but those prior read, to me, scratchy, missing)���Graham’s emphatically a nature writer.

Which, of course, she’s always been: you see it now, here, echoing back to even Hybrids of Plants and Ghosts, her first collection: where the earlier Selected begins with that early greatness “The Way Things Work”���a poem I cannot read as anything other than a poem about connecting, thinking-into-feeling-into-living���From the New World begins with “Tennessee June,” a poem with similarities to “Work” but, instead of being accretive and trying to connect, “Tennessee” ends on “the spirit breaks from you and you remain,” which is compelling and gorgeous, but is decidedly different from the feeling offered by “The way things work / is that eventually / something catches.” Those are radically different dramas, with I’d argue wholly different stakes: the emphasis in “Tennessee” seems on where the act of existing remains once the spirit’s broken “from you,” and the emphasis in “Work” is on the catching, on the moment in which existence grinds gears with some other to breathe or enact living.

Which, of course, she’s always been: you see it now, here, echoing back to even Hybrids of Plants and Ghosts, her first collection: where the earlier Selected begins with that early greatness “The Way Things Work”���a poem I cannot read as anything other than a poem about connecting, thinking-into-feeling-into-living���From the New World begins with “Tennessee June,” a poem with similarities to “Work” but, instead of being accretive and trying to connect, “Tennessee” ends on “the spirit breaks from you and you remain,” which is compelling and gorgeous, but is decidedly different from the feeling offered by “The way things work / is that eventually / something catches.” Those are radically different dramas, with I’d argue wholly different stakes: the emphasis in “Tennessee” seems on where the act of existing remains once the spirit’s broken “from you,” and the emphasis in “Work” is on the catching, on the moment in which existence grinds gears with some other to breathe or enact living.

Of course, the selections from *all* Graham’s books are different, Selected to Selected. Not for nothing, the more recent books���Sea Change and Overland and PLACE���are exceptionally well-represented in From the New World, and there’s a way this reads that almost feels as if the glory of the now-early-middle-career books (Materialism, The Errancy, Swarm and Never) was a blip, some detour. In other words: if you fell hard for Graham based on the poems you read in The Dream of the Unified Field, you might find a different poet on these pages. I, anyway, have.

Again: this is not a problem. But the central drama of Graham’s poetry has now, with From the New World, been firmly grounded as a consideration of humans’ place in the world, how we interact with the world, and what we do to the world���and, ultimately, the peril we’ve put the world in, through our actions and ideas. Something about responsibility. This is a radically, radically different drama than the one you’d be forgiven for believing was the central one operating in Graham’s work up till now: if you know Graham’s work, you know that her Overlord and Sea Change���and certainly to a degree Never, though not as overtly���are engaged fairly directly with climate change, with the havoc humans have wrought on the planet. Sea Change and Overlord, for me, were the first misses in her long career: neither book finally ever cohered for me, not deeply, and I could never find or feel the pressure I’d once come for. What From The New World does, however, is recast all the poetry (or, actually, not really recast, but more re-jigger so that the stuff that’s already there is specifically highlighted) so that the questions of cost and humanity-in-relationship-to-the-environment is paramount. This is not a bad thing, but it is a *different* thing than what you may have understood to be happening in Graham’s poetry if your entrance was���like mine���through her work up until the early ’00s.

So: this is, for me, a weird book. It’s endlessly beautiful: I dare you to read any early or late or in-between stuff���”Reading Plato” or “Lapse” or “Dusk Shore Prayer”���without succumbing to the whallop there on offer. Dig it: nobody writes such Hugeness as Graham. Nobody. I’ve read for hours and days and months and years. Nobody has, in any way, tried to include/engage-with/tackle this much. Not even close. And so if you’re just finding your way to Graham, please, by all means: get From the New World, and allow the enrapturing to do it’s thing. If you’re however interested in a longer strand of American poetry���one that’s trying to wrestle with the most deeply gnarly questions of being and thinking and feeling���again, that subjectivity Chiasson notes so well���go ahead and get New World, but also, please, get The Dream of the Unified Field, and then read all the rest of her work. Maybe this is just a too-long way of saying: the selected poems of ANY poet this good is bound to be complicated, because in doing the so-muchness they’re engaged in, any fractioned presentation of their work precludes the oomph available through the totality of the work.

The point of this review���consideration, really���is simply to note that the Jorie Graham poetry you’re reading in From The New World is a rearranged approximation of one of contemporary poetry’s Greatest Writers, and please just know that the environmental focus one can’t help but notice in this collection is, I’d argue, simply one thread of the larger amazement she’s been now braiding for forty years (and, clearly, I believe another thread���the thing about connecting, self, and subjectivity���is more something, I can’t say what), and while it’s great, I can’t help, as a huge admirer of other facets of her work, but note that the other threads are equally monumental and transcendant. Anyway. If Graham doesn’t win a Nobel eventually, we should all be sad: she’s gunning for a glory so rare it’s not even aimed for by most practicing writers. Finally, the point of all of this is just this: Read Jorie Graham. Everything past that immutable fact is so distant as to be dismissable.